By Michael Jones, RiverFront Investment Group

Since the 2008 financial crisis, the global economy has struggled with sluggish growth and periodic fears of a deflationary spiral similar to the Great Depression. Many economists and prominent investors have dubbed this environment the “new normal” under the assumption that demographics and government debt burdens make this lackluster economic environment a permanent fact of life. We disagree. We believe that the cumulative impact of policy changes in the US and Europe creates the potential for a significant acceleration in global economic growth. At the same time, we think the undeniable disinflationary pressures in the global economy are likely to keep inflation subdued and central bankers relatively accommodative even as growth accelerates. In our view, demographics will continue to depress overall wage growth, but rapidly rising wages for new workers could prevent the kind of populist backlash that would derail an economic boom. The combination of faster growth, modest inflation and accommodative monetary policy could allow the current bull market in global equities to continue for many years in the future, and potentially rival the long disinflationary boom of the 1980s and 1990s.

Characteristics of a Disinflationary Boom

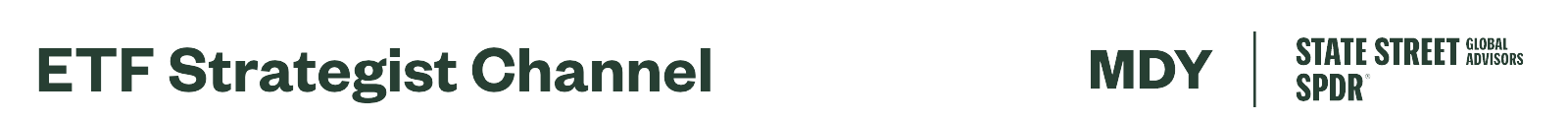

A disinflationary boom is a relatively rare economic condition in which structural forces keep inflation low despite an extended period of strong economic growth. The last disinflationary boom began in 1985 when the Volker Fed’s anti-inflationary policies got a boost from collapsing oil prices – the subsequent economic boom lasted for nearly 15 years with US growth averaging about 3.5%. By contrast, economic growth since the Great Recession of 2008 has averaged only about 1.5% in the largest developed economies (US, Eurozone and Japan). Policy mistakes produced a prolonged double dip recession in the Eurozone (2012-2013) and triple dip recessions in Japan (2011 and 2014).

Despite this dismal recent experience, we believe that conditions are in place for average growth in developed economies to accelerate closer to 2.5%. That could boost global GDP (including emerging economies) from its current desultory 3.0% to 3.5% range into a potential range of 4.0% to 4.5%, with a corresponding acceleration in corporate profitability. Despite faster growth, we believe that the deflationary forces of demographics, technology (especially energy extraction technology such as fracking) and global competition should keep inflation in developed economies under 2%. Such modest inflation pressures would allow global central banks to remain relatively accommodative as growth picks up, providing a very favorable backdrop for global growth and equity prices.

We first identified the potential for a global disinflationary boom in our 2016 outlook. We only assigned a 30% probability to this “Optimistic Scenario” in recognition that a retreat from globalization in the UK and US, or stalled economic reforms in Europe and China, could derail an optimistic forecast. These potential obstacles to a global deflationary boom became all too real in the wake of 2016’s unexpected political and economic developments (Brexit, Trump’s campaign pledge to withdraw from NAFTA, defeat of the Italian reform referendum, China’s suspension of its State-Owned Enterprise reform program and resumption of capital controls). However, we believe these setbacks have thus far proven far less severe than initially feared and been largely offset by 2017’s positive political and economic developments (extensive deregulation in the US, an economic reform mandate in France and accelerating infrastructure spending through China’s “One Belt, One Road” initiative). As a result, the potential for a global disinflationary boom is back on track and we believe the odds of such a boom have risen to about 50%.

Primary Catalysts for a Boom – Growth-Oriented Policies in the US and Europe

Demographics and the aftereffects of the 2008 Great Recession are often blamed for the subdued growth seen in the global economy since 2008, but we believe that significant policy mistakes in major developed economies were also to blame. The US reacted to undeniable recklessness by major financial institutions with a comprehensive re-regulation of the banking industry. The combination of higher capital requirements, innumerable new regulations and billions in fines for not following the old regulations diverted bank resources away from fostering economic growth though small business lending. Unlike large corporations, small businesses are largely dependent upon bank funding in order to grow. Increased health care, labor and environmental regulations also disproportionately impacted small businesses since they typically lack the legal resources to cope with a flood of new regulatory requirements.

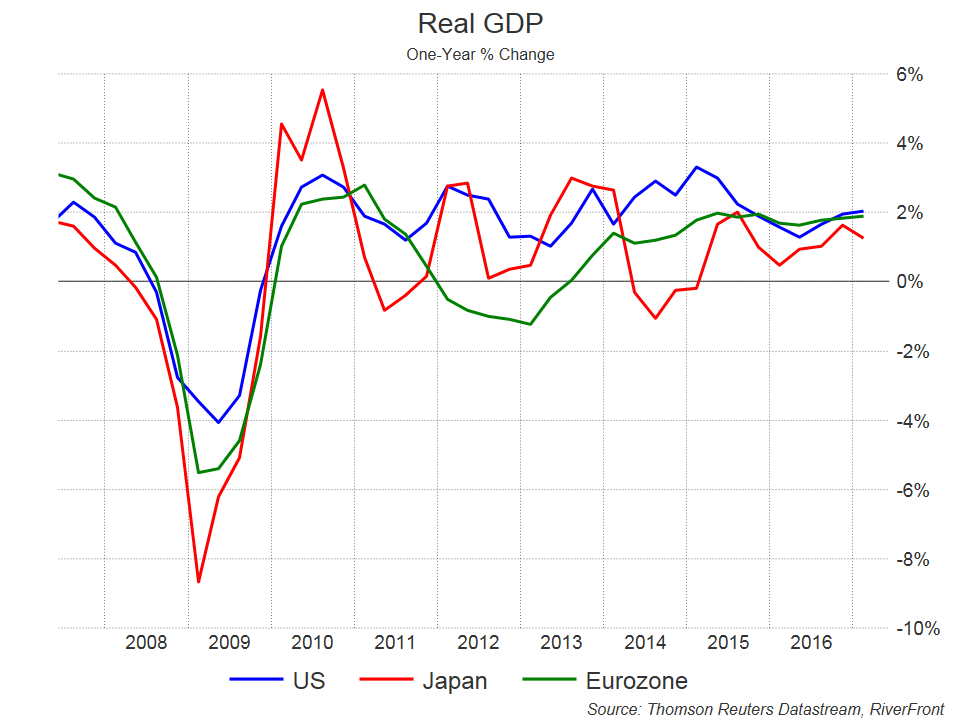

Much of the policy stimulus hoped for in the wake of President Trump’s election has been delayed by internal divisions within the Republican Party. By contrast, the regulatory initiatives that President Obama implemented with his “phone and pen” are rapidly being undone by President Trump’s application of the same tools. The result has been a surge in small business confidence, as shown in the adjacent chart.

These small companies are the primary source of job creation in the US economy. Renewed confidence and funding availability for this critical sector of the US economy could provide a significant source of incremental growth in the US.

European policymakers tightened fiscal and monetary policies in 2011 despite an escalating debt crisis across southern Europe (Greece, Italy, Spain, etc.), thereby triggering a second deep recession in 2012 and 2013. Mario Draghi’s leadership at the European Central Bank brought a much better policy mix and improved economic growth, but could not erase the deep structural flaws in the euro bloc exposed by the European debt crises.

Germany embraced sweeping labor market reforms in the early 2000s and transformed its economy into the super-efficient export machine of recent years. Countries within the euro bloc that refuse to embrace similar reforms simply cannot compete. Although better policies from Draghi can buy time, every country in the Eurozone will eventually have to decide whether to embrace reform or leave the common currency, in our view. This uncertainty over the future of the euro has weighed on business confidence and depressed economic growth.

We believe the recent French elections have the potential to transform the growth prospects for both the Eurozone (as the world’s largest economic bloc) and the global economy. French President Macron has been granted an overwhelming parliamentary majority and a mandate to enact sweeping labor market reforms. If he is able to achieve these reforms, then France could experience the kind of reform-driven growth seen in the US and UK in the 1980s, Germany in the 2000s, and Spain over the past two years. French reforms could also secure the future of the euro by ensuring that both France and Germany remain at the heart of the euro bloc. That reassurance could profoundly improve the investment environment in Europe and across the global economy.

Disinflation is Likely to Continue, but Demographics are Masking Accelerating Wage Gains

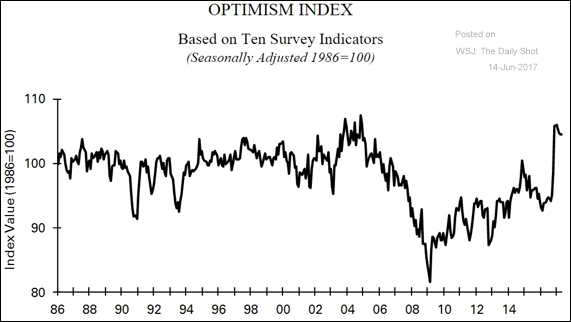

Despite years of extraordinary monetary policy and the recent upsurge in economic growth, inflation in the major developed economies appears to be once again rolling over and headed back down. As shown in the chart below, US inflation has fallen below 2%; European inflation is back below 1.5%, while Japanese inflation is hovering just above 0.0%.

Globalization and competition among global companies are well-established sources of downward pressure on prices, as are technological innovation in industries such as retail and financial services. Manufacturing costs are plummeting thanks to robotics and the increasing adoption of 3-D printing – CPI data indicates that US prices for core manufactured goods have fallen between -0.5% and -1.0% per year for the past three years. Fracking and the emergence of the US as the swing producer in oil markets has kept oil prices range-bound between $40 and $60, and as technology advances we believe that trading range will likely decline over time.

This relentless price pressure is painful for the impacted industries and workers, but disinflation driven by global competition and technological change is generally considered good for the global economy so long as worker wages rise despite the disinflation. If real wages don’t rise for the average worker, the populist backlash we have already seen could get worse and derail any potential boom.