By Larry Whistler, Nottingham Advisors

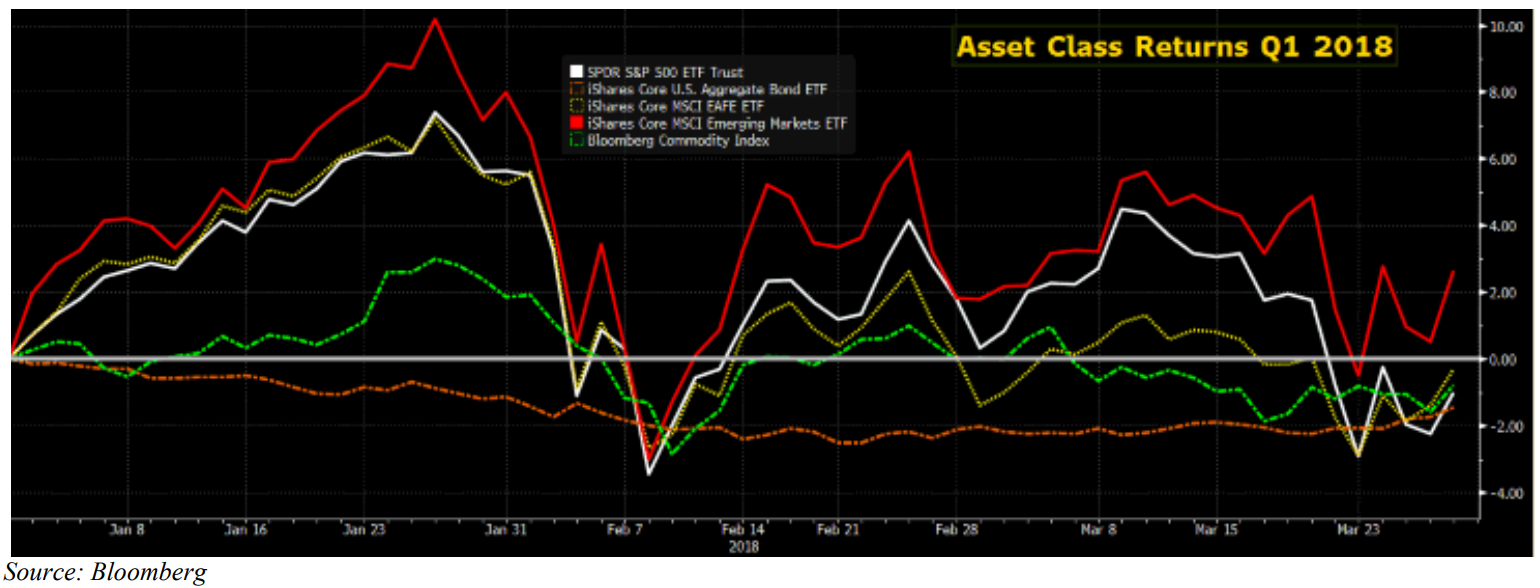

An investor that went to sleep on January 1st and awoke on April 1st, might easily be led to believe nothing much happened in financial markets during his or her slumber, simply by looking at return numbers.

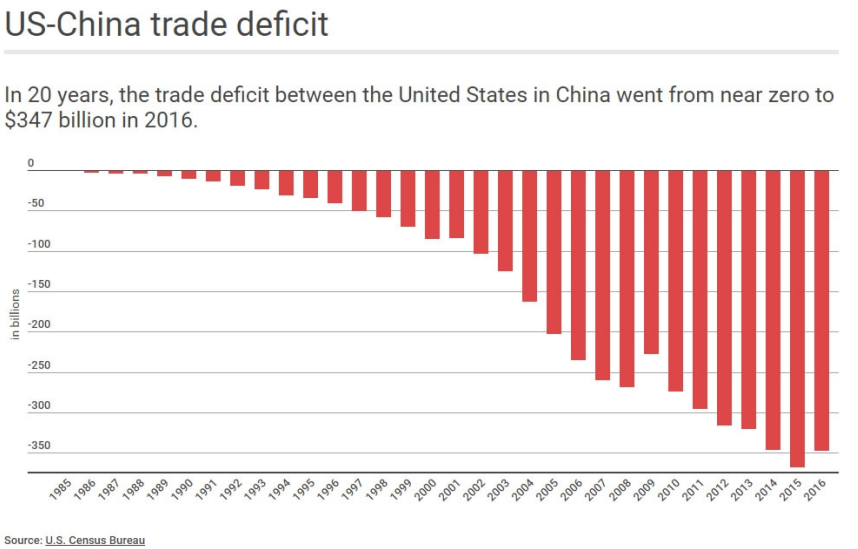

The S&P 500 lost -.75% during this timeframe, while international developed markets lost –1.6% and emerging markets gained +1.24%. Bond returns were slightly negative in Q1 while gold gained +1.7% and oil +7.7%.

Anyone paying a little closer attention (and perhaps having read our mid-February missive) will know that volatility returned with a vengeance in Q1, bringing a swift end to one of the longest periods of investor complacency that we can remember.

![]()

In our February letter, we suggested that the root causes of the surge in volatility weren’t clear at that time.

Upon further study and reflection, I’d like to suggest three main triggers for the rise in investor uncertainty:

1) fear over the possibility of a trade war with China, 2) uncertainty around the pace of future interest rate increases, and 3) our duly elected “Twitter-in-chief’s” preference for chaos over order. Trade In 1817, British political economist David Ricardo developed his theory of comparative advantage as a way to explain why countries engage in international trade. The main idea is that even though two countries may have the same capacity to produce two goods, if each country produced only the good where they had a comparative advantage, such as low-cost labor, and then engaged in free trade, everyone would be better off in the aggregate.

Translating that into the 21st century, China has a distinct advantage over the US centered on low-cost labor.

They can produce many goods far cheaper than we can here in the US. The US has a decided advantage in technology and advanced manufacturing. Although the iPhone is assembled in China, it is designed using intellectual property largely developed here in the US. For the past few decades, American consumers have been the beneficiaries of low-cost Chinese labor. Clothing, TV sets, refrigerators, you name it, all have seen steady price declines over time as cheap labor and advances in manufacturing capability have combined to lower the cost of producing these goods.

The down-side to this has been the loss of decent paying US jobs, which have moved overseas. From textiles to manufacturing to basic tele-service positions, US companies have benefitted by moving these positions overseas. (At this point I would recommend you read JD Vance’s compelling narrative Hillbilly Elegy for a better understanding of the impact this has had on rural America.) As we welcome low-cost Chinese made goods into the US, China remains a relatively closed market. Our trade deficit with China has soared, reaching – $375bn in 2017.