The recent move to potentially delist Chinese companies from American exchanges has made for good headlines. But the risk to Chinese equities—particularly the non-state-owned segment of China or emerging markets, where China is about one-third of total weight—is minimal. The risk comes mainly from the expected growth potential of the global economy.

Unless the U.S.-Chinese relationship reaches a point of no return with substantial escalation to financial “nuclear war,” which would be even more severe than the trade conflict, investors should realize that the risk from current conflicts is secondary to fundamental earnings factors driving Chinese equities.

I’ve broken down six reasons why I believe that the delisting threat is insignificant.

1. The Bill Has Not Yet Passed in the House

First, the Holding Foreign Companies Accountable Act, which passed the Senate on May 20, 2020, still needs to pass the House to be enacted. Though there is broad bipartisan support, the fact that it has not passed as of August suggests that companies would be able to delist in an orderly fashion.

As passed, the law was also vague on the timing and process of delisting, asking companies to submit audits to the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB), which oversees all U.S. public companies’ audits. Failure to provide information for three consecutive years would lead to the delisting of a company’s shares. The general interpretation of this requirement is that companies will have three years to sort through the process.

This point is crucial, because if delisting happens in an orderly fashion, then a natural home for delisted companies such as Alibaba and Baidu is the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, which has actively courted them to relist their shares. Larger companies such as Alibaba and JD.com have already finished dual listing in Hong Kong and New York, with several other companies preparing for dual listing in Hong Kong.

2. ETFs Are Impacted Differently Than Individual Stocks

That brings us to the second point: If these companies already have dual listings by the time the law passes, investors in exchange-traded funds (ETFs) who seek tracking indexes—such as the WisdomTree China ex-State-Owned Enterprises Index—wouldn’t even notice the impact on their portfolios. A swap of New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) shares for Hong Kong shares would most likely be treated as a corporate action, which happens daily in the background for portfolio managers. For investors who directly own those stocks instead of ETFs, it may be a bit more complicated, depending on how their respective brokerages handle corporate actions.

3. The Role of the PCAOB

The history of the PCAOB is as much about regulatory power as it is about protecting investors from fraud. The PCAOB was created in response to the October 2001 Enron scandal. Enron’s auditor is believed to have colluded with the company to manipulate and falsify its accounting records. The PCAOB is supposed to be the auditor’s auditor, regulating companies such as Ernst &Young (EY) and PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC). The current conflict is this: Does a Chinese company such as Alibaba fall under the regulatory jurisdiction of the U.S. PCAOB because it is listed on the NYSE, or under the Chinese equivalent of the PCAOB because it is a Chinese company?

Most of the Chinese companies listed on the NYSE use the Chinese branches of the Big Four U.S. auditors. Chinese firm Luckin Coffee—which has been accused of committing accounting fraud—used EY as an auditor. But most news articles missed the fact that EY didn’t certify its recent annual report, which is believed to have contained the period when the fraud allegedly occurred. Presumably for legal reasons, EY has been silent on whether its auditing has independently uncovered fraud. Emerging market companies generally carry a valuation discount for the possibility of accounting fraud, so it is not necessarily evident that delisting would help protect U.S. investors.

4. Other Risks in Chinese Equities (Besides Delisting)

Chinese equities have other risks beyond delisting. If U.S. public opinion turned sharply against China and started to view investment in any Chinese stock as analogous to what happened in South Africa during the apartheid era, there would be substantial divestment that could lead to lower valuations. That opinion has not translated into mainstream investment action so far. Based on most of the sanctions imposed to date, the non-state-owned segment of Chinese equities is likely to be less politically controversial than banks or state-owned energy firms.

Based on the U.S. response to Chinese restrictions on airlines flying between the two countries this year, as well as TikTok and WeChat executive actions and legal challenges, a theme of “reciprocity in market access” seems to be driving future economic conflicts.

5. Potential Outcomes of a Reciprocity-Based Strategy

This reciprocity-based strategy does not suggest a dramatic escalation of U.S.-China financial conflict, such as forbidding U.S. investors from investing in any Chinese equity, whether listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange or the Chinese mainland.

This kind of escalation of financial “nuclear war” would be a bigger conflict than the current trade war. Equity markets would suffer if that worst-case scenario were realized.

The hope, the belief, is still that the U.S. and China will work out some issues based on mutual benefits and common ground, with whack-a-mole conflicts across broad economics and politics persisting decades down the road. We can only follow Winston Churchill’s advice: “It is a mistake to try to look too far ahead. The chain of destiny can only be grasped one link at a time.”

6. The Primary Factor (Expected Earnings Growth Rate) Driving Chinese Equities Has Not Changed

The final point is that the primary factor driving Chinese equities is the expected earnings growth rate and whether actual growth supports current valuations.

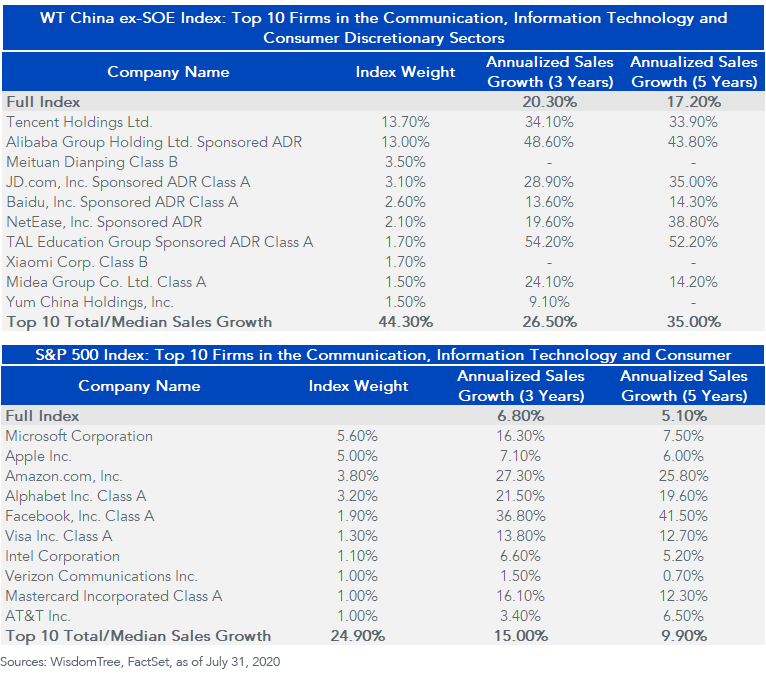

Pinduoduo, an e-commerce company that directly competes with Alibaba and JD.com, has seen heavy volatility recently. It delivered high growth, but not as much as the Street had hoped for in its rich valuation. The top non-state-owned Chinese firms that are the most vibrant segment of the Chinese economy have delivered significant sales growth compared to top U.S. firms in the S&P 500.

Future earnings and stock price increases of these companies will come from both U.S. and Chinese economic growth continuing to support global growth.