I think it’s a bit of a truism that, as a global population, “Wall Street” as a conceptual entity doesn’t engender much trust. Wall St. vs. Main St. remains one of the go-to false dichotomies of American political discourse, and probably for a good reason: in a capitalism-forward society — which we inarguably are — we’ve all been well trained to assume that everyone in the money business is in it to, well, make money. And absent some sort of fiduciary relationship, it’s every person for themselves. So I get why there’s an endless cavalcade of negative press about “Payment for Order Flow,” or PFOF.

PFOF is a series of legally sanctioned backroom deals that route retail orders away from the “lit” exchanges (that is, what you see on your trading screen) and directly into the hands of a half dozen major trading firms like Citadel and Virtu and Jane Street. If you’re a regular follower of /r/WallStreetBets on Reddit or wade into the public cesspools of individual-trader social media, there is no greater villain than Citadel’s CEO, Ken Griffin, and no greater conspiracy than PFOF.

And just this week, the SEC decided to ignore it. As they should.

What It Is

PFOF, at its core, is a way of getting a lot of tiny trades out of the teeth of the National Market System, the core set of rules and procedures established by Reg NMS, the 2005 attempt by the SEC to modernize U.S. markets by introducing the National Best Bit Offer (NBBO) — essentially a universal limit order book with a set of requirements about how trades are executed against it, or around it. For the past 18 years, folks like me have been whinging about the minutiae of the rule and all of the unintended consequences (which arguably contributed to all sorts of market hiccups over the years). But the core idea sounds great on paper: There’s a big public record of the best bid and ask for every listed security and rules to make sure that every investor, no matter how small (as long as you’re over 100 shares), gets the same treatment.

However, one important nuance to Reg NMS’s order protection rules is that your brokerage can choose to route your trade off the exchange if they can get you a better price. In the patois of trading, that’s called “price improvement,” and if you’re an advisor or individual investor, I’d be shocked if the vast majority of the trades you submit don’t execute slightly better than you expect. You wanna buy the GME right now when it’s quoted at 26.60/26.62, so you put in your order at Schwab or Fidelity to buy 50 shares at 22.62, figuring you’ll probably get a fill. And low and behold, you get filled at 26.615 — half a cent better than you ever thought possible.

You got that half-a-penny because instead of your order getting blasted out into the limit order book waiting for a matching order, your order got routed directly to Citadel (or whomever), who simply took your trade for better than you expected. Because small-lot retail trading is largely random and has very little information, it’s not unlikely that seconds later, that same firm buys 50 shares of GME for 26.605. Both customers get better-than-available prices, and Citadel theoretically pockets the penny difference.

Citadel likes this business because it’s cheaper and easier than their normal business of making a public lit market (which they are doing at the same time) and because the chances they get run over by a bunch of retail investors suddenly becoming very smart and very fast is nonexistent. Schwab likes it because Citadel cuts them in on a piece of the action, to the tune of about 10% of Schwab’s revenue in any given quarter. That’s how they (robin hood and most other brokers) offer commission-free trading.

What It Ain’t

Let’s run through the common WallStreetBets hair-on-fire complaints:

First off, “hidden” this is definitely not. Every broker reports exactly how much PFOF they receive and to who they route their trades. FINRA, which is in the job of slapping brokers when they break the rules, has its own set of guidelines for how brokers have to route trades and track where all the money is going, and they’re rarely asleep at the switch. FINRA loves fining people for execution violations like they’ve done with Robinhood. I’m not saying bad/weird stuff doesn’t happen — this is all a for-profit ecosystem, and the incentive is always to push the limits. I’m saying the system does, in fact, catch and punish folks with shocking regularity.

Second, it’s not a “first look” at big market moves that the PFOF firms front run. The internet is just loaded with conspiracy theories about how some algo is monitoring 30 share blocks of GME and then betting the hedge-fund-farm on this inside information. Putting aside the fact that this is patently illegal and heavily monitored, there’s not actually any evidence that having a first look at small-lot orders tick by tick gives anyone a particular advantage. In fact, the whole reason market makers like this kind of internalization is because they really don’t have to worry about information content — it’s raw facilitation. This is very different than, for example, a large institution trying to buy a 100k share position. That trade has a ton of information, and concealing that kind of information is why dark pools, algo-trading, and big risk-taking desks exist. None of that has anything to do with PFOF.

Third, while there are large amounts of money involved — actual billions in implied spreads — the actual impact on individual investors is positive (some estimates put it at about $4 billion in net price improvement), but also tiny — sub-penny, sub-basis-point — in terms of trade value. It’s nice to imagine a theoretical world where all that money goes right to investors, but until we have a blockchain-based 100%-at-risk zero-time settlement, someone will make money sitting in the middle. We designed the system that way on purpose.

What, Me Worry? Tweaking the Minutiae

Are there things about the current system that could be better? Of course. But it’s not clear what to tweak.

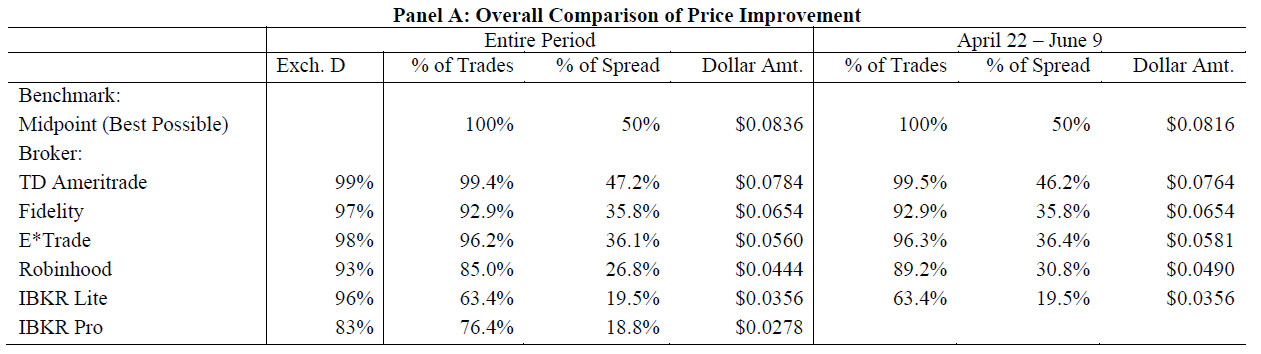

The most interesting research done on this issue was published quite recently by a collection of professors in notable finance Ph.D. programs (Schwarz, Barber, Huang, Jorion and Odean), who took a very “jump into the rabbit hole” approach (good summary here, actual paper here). I can’t gush enough about the methodology: they opened a bunch of brokerage accounts and placed 85,000 simultaneously triggered market orders over a period of months using small lots and created their own real-world data set (with $15.4 million in notional!), so they didn’t need to rely on any self-reported data or regulatory filings. They then demanded (as they’re legally allowed to) all of the order routing information for every single one of those trades so they could match it against all like-trades at the same time.

What they discovered was, frankly, the beautiful mess that is modern markets. While essentially every trade had price improvement, an unadulterated win in my book, there was no rhyme or reason to which trades did better than others. It didn’t matter which broker took more PFOF or whether they took PFOF at all. It didn’t matter whether they chose commissioned brokers. It is, essentially, a random walk from the investor’s perspective of how much price improvement they receive (although certainly some brokers seem to do consistently better, it doesn’t seem to have anything to do with whether they are or aren’t being paid more or less for the flow).

Put another way: retail orders in modern markets receive the best prices at any given moment but within an unpredictable band. That in itself is a victory — 20 years ago, I don’t think anyone would have suggested retail orders were getting the best prices. Are they getting the best prices they could get? Probably not. There’s always efficiency to be squeezed out of any system, and I suppose it’s reasonable to put more guardrails around how PFOF flows back to individual investors through services, discounts, or prices.

But I would suggest you consider the alternative. We’ve decided collectively that the government should not run the markets (which isn’t the case, say, in Shanghai, where the government, in fact, owns the market). Through Reg NMS, we broke up the oligopoly of exchanges and their members controlling all pricing and fragmented the process of order routing and price discovery, with the explicit goal of improving market efficiency — moving as many trades as possible at prices considered on average fair. The SEC could have decided just to ban PFOF, which would have removed the open and transparent incentives here, but I’m not convinced that would have resulted in any more money in the pockets of investors or even less money in the pockets of Citadel and Virtu. Brokers would have to either go back to charging commissions or generate less transparent revenue (like cash management spreads).

I, for One, Welcome Our PFOF Overlords

Look, I get it. Nobody likes to make Ken Griffin richer. I’m not on his holiday card list. And as much as I love how much fodder PFOF has given Matt Levine at Bloomberg over the years for great and funny blogs, I’m a big believer in working with what’s in front of us. Is the current system perfect? Of course not. But we have tasked the for-profit corporate sector with maintaining the plumbing of U.S. markets, and there’s a cost to that. Turn off this system, and that cost will simply shift — either into frictional heat through a less efficient system or into a different set of players (exchanges, most likely).

But as an advisor managing client portfolios or an individual investor trying to patch together a portfolio out of this motley quilt of ETFs and stocks?

Use a limit order, and save the brain cycles for something more important, like talking to your clients or spending time with your kids.

For more news, information, and strategy, visit VettaFi.com.