For new investors, the world of finance can appear daunting. But among the sea of investment options, Treasury bonds (often just called “Treasuries”) are a pillar of stability and reliability. In this beginner’s guide, we’ll delve into the ABCs of Treasury bonds, why they are often considered the bedrock of the financial system, and the different kinds available to investors.

At its core, a Treasury bond is a loan from you, the investor, to the U.S. government. When you purchase a Treasury, you’re essentially lending money to the government. In return, the government commits to pay back the full amount (the principal) by a specific date, plus a fixed interest rate along the way.

Treasury bonds are one of the main ways the U.S. government finances its operations, from infrastructure projects to paying off older debt. They have been issued since 1917 when they were called “Liberty Bonds” and used to finance the nation’s participation in World War I.

The Financial System’s Bedrock

The Department of Treasury issues Treasury bonds. They are debt guaranteed by the U.S. government, as laid out in the Constitution in Article I, Section 8, Clause 2. The U.S. has never defaulted on its debt, so these bonds come with very little risk of default.

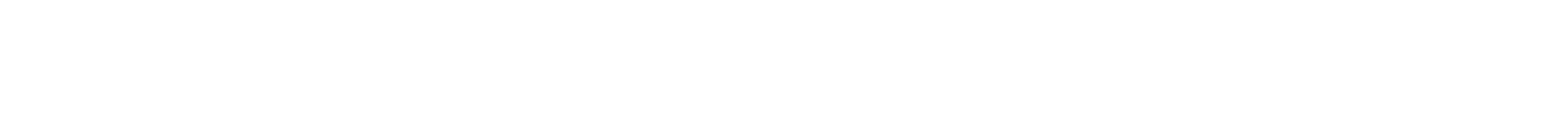

Treasurys are highly liquid, meaning investors can easily convert them into cash with minimal market impact. According to the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association, year to date through September 11, 2023, their average daily trading volume exceeded $750 billion. ETFs make liquidity even more accessible for retail investors, who can purchase a portfolio of bonds on exchange rather than transacting for individual ones with a broker.

SIFMA

The interest rates on Treasuries serve as a benchmark for other interest rates in the economy. Everything from mortgage rates to corporate bond rates often move in tandem with Treasury yields. In fact, the rate of Treasurys is known as the “risk-free rate” — bonds that carry default risk, such as those issued by corporations — yield a higher interest rate than Treasuries that are at the same maturity.

During economic downturns or times of high inflation, investors flock to the safety of Treasuries. This is known as the “flight to quality,” a phenomenon that makes the asset class a valuable tool for portfolio diversification.

Different Types of Treasurys

“Treasury Bonds” is a blanket term that covers several different kinds of debt, each with its own set of characteristics:

Treasury Bills (T-Bills): These short-term securities mature in one year or less, with maturation periods ranging from four weeks at the short end to 52 weeks at the long end. Investors buy them from the Treasury at a discount but do not receive interest payments during the period to maturity. Instead, the investor’s profit is the face value paid at maturity minus the discounted purchase price.

Treasury Notes (T-Notes): These have maturities ranging from two to 10 years and pay semiannual interest to holders. They are useful for investors looking for a balance of safety and, in normal times, slightly higher yields than T-bills.

Treasury Bonds (T-Bonds): These have the longest maturity, ranging from 20 to 30 years. Like T-notes, they pay semiannual interest. Investors looking for long-term safety and consistent income often gravitate toward T-bonds.

Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS): These are designed to protect investors from inflation. The principle of TIPS rises with inflation and falls with deflation. Interest is paid semiannually and is applied to the adjusted principal. If inflation rises, the interest payments increase. The Treasury issues these securities for terms of five, 10, or 30 years.

Treasury Floating Rate Notes (FRNs): These are the newest instruments to be issued by the Treasury Department. Unlike traditional fixed-rate notes, which pay the same interest rate over their entire life span, FRNs have an interest rate that can change over time. Issuance of these started in 2014, but they became more popular during the rising interest rate environment of 2021-2023.

The Yield Curve

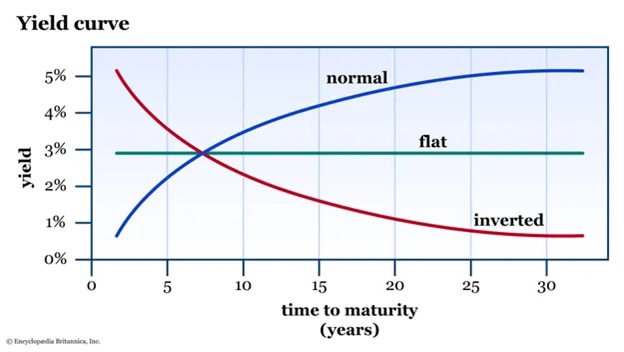

The Treasury yield curve represents the relationship between the interest rates (or yields) and the maturities of U.S. Treasury securities. Graphically, it is a representation that plots the yields of different Treasury securities, ranging from short-term bills to long-term bonds, against their respective maturities.

When the economy is growing “normally,” typically the yield curve slopes upward. Short-term yields are lower than long-term yields, indicating that investors demand higher returns for a longer period. Bonds would yield more than notes, which in turn would yield more than bills.

On the other hand, an inverted curve occurs when the economy may be slowing, and is often viewed as a predictor of economic recession. Inversion indicates that investors expect lower interest rates and slower growth in the future. An inverted yield curve has foreshadowed all 10 recessions from 1955 to 2020.

The yield curve today is significantly inverted. As of September 13, 2023, three-month bills yield 5.55%, while 30-year bonds yield 4.34% — over a percentage point less. Still, the economy is doing well, and it has been doing well over a year since the curve first inverted.

Conclusion

Ultimately, U.S. Treasurys are a great starting point for new investors building their first portfolio. The securities offer unparalleled safety and liquidity. They also serve as a cornerstone of the global financial system. Moreover, Treasurys are versatile. They can diversify a portfolio, protect against inflation, or allow an investor to simply dip their toe into the world of investing. Whatever their purpose in a portfolio, Treasuries can provide a solid foundation on which to build your financial future.

For more news, information, and strategy, visit the Financial Literacy Channel.