By Bill O’Grady & Patrick Fearon-Hernandez, CFA

(Due to the Independence Day holiday and a short summer hiatus, the next report will be published July 12.)

As is our custom, we update our geopolitical outlook for the remainder of the year as the first half comes to a close. This report is less a series of predictions as it is a list of potential geopolitical issues that we believe will dominate the international landscape for the rest of the year. It is not designed to be exhaustive; instead, it focuses on the “big picture” conditions that we believe will affect policy and markets going forward. They are listed in order of importance.

Issue #1: A New Hegemonic Model

One of our persistent themes has been that the Cold War model of American hegemony has outlived its usefulness. When the Soviet Union collapsed, a new model should have emerged. However, it never did. Instead, the American foreign policy establishment removed its focus on containing the Soviets and shifted to a Wilsonian model of foreign policy. This model argues the U.S. should engage in policies to rid the world of human rights violations and bad behavior. The Wilsonian mindset, adopted by the neoconservatives on the right and the liberal order supporters on the left, framed the winning of the Cold War as a victory of values. And so, continuing and escalating the use of that model would expand liberal democracy, thus enforcing American values and making the world a better place.

The policy has not panned out either in the foreign policy arena or in finding support from the American domestic situation. Incursions in the Balkans, Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya have either led to unclear outcomes or extended military operations. The incidence of this policy has fallen hard on military families who have seen their soldiers engaged in multiple deployments, most of which had no obvious exit strategy.

During the Cold War, there were situations the U.S. didn’t get involved in because they were seen as either inside the U.S.S.R.’s sphere of influence or not in an area of concern for either superpower. But after the Cold War ended and the priorities shifted, the U.S. was drawn into global problems that did not have a strategic rationale.

A second factor in the Cold War model of American hegemony was that the U.S. became the provider of economic security to the world. The U.S. Navy protected the world’s sea lanes and assisted in preventing historic flash points[1] from devolving into hot wars, which prevented long-term enemies from fearing each other and fostered global trade. In addition, the U.S. provided the reserve currency, accepting large current account deficits to provide an ample supply of dollars to the world. This model encouraged foreign nations to build their economies on export promotion, using the American consumer as a source of reliable demand.

The problem with the current model of hegemony is that the incidence of the policy falls on the less affluent who tend to join the military and whose jobs are at risk from foreign trade. The affluent are generally supportive of maintaining the status quo; they benefit from globalization and generally don’t bear the cost of military actions.

Overall, we don’t think the current model is politically sustainable. The voters who elected Barack Obama wanted a different outcome; when he proved conventional in his policies, they opted for Donald Trump. Although the election of Joseph Biden signals support for the Cold War model of hegemony, his victory was narrow and even among his supporters there is a general dissatisfaction with the model.

If the Cold War model can’t be sustained, what replaces it? There are generally two options. The first is the U.S. abandonment of hegemony, which leads to global regionalization, the breakdown of globalization, and likely more frequent and expanded regional conflicts, until, as history shows, another hegemon emerges. Although we often show the historical parade of hegemons as seamless, in reality, it is not. Periods where a reigning hegemon is fading and a new one hasn’t emerged are fraught with distress. For example, the gap between hegemons in the late 1700s led to the American and French Revolutions and the rise of Napoleon. When the British were fading but the U.S. refused to accept the superpower mantle, we had two world wars and the Great Depression. We have feared a similar situation in the coming years as a new hegemon isn’t obvious. Although China is presumed to take that role, its demographics will make that difficult.[2] Thus, if the U.S. does remove itself from the role, it could be a decade or two before a replacement emerges.

However, there is another possibility. The U.S. could behave in a fashion similar to earlier hegemons. In other words, America could move from being a benevolent hegemon toward a malevolent one.[3] In this model, referred to as “offshore rebalancing,” the U.S. would no longer guarantee security in the Far East, Middle East, or Europe. Instead, it would act as a balancing power, tipping the scales to prevent Germany or Russia from dominating Europe, Iran or Turkey from dominating the Middle East, or China or Japan from dominating the Far East. This is a tricky policy to employ. First, it requires remarkable foreign policy talent, requiring the practitioner to know exactly when to intervene. Second, it is difficult to “sell” to the electorate in a democracy. The ideal that nations have no permanent friends, only interests, is a bit more Machiavellian than most voters would tolerate. In practice, this would mean setting Iran against Israel and the Arab states and ensuring that neither side dominates. It would mean signaling to Japan and China that they could not rely on the U.S. to pick sides in a conflict. U.S. policymakers might also restrict access to the U.S. consumer, either by trade barriers or by a deliberate attempt to drive down the dollar’s value.

Needless to say, the idea of offshore rebalancing hasn’t been popular among the foreign policy establishment. But, if the options are either withdrawal or malevolence, the latter may be a better option than the former. In our opinion, the current model of benevolence is no longer sustainable within the American political system, so it probably is no longer an option.

Issue #2: China Increasingly Dominating the Hong Kong Stock Market

It’s now been a year since Beijing imposed its new national security law on Hong Kong, and it’s clear that the legislation has helped bring the city-state under the mainland’s political control. More broadly, trends over the last year make it clear that Hong Kong is losing its previous unique, autonomous character and is being more closely integrated with mainland China politically, economically, financially, and socially.

Chinese authorities haven’t been shy about applying the security law’s draconian punishments to clamp down on civil liberties in Hong Kong. As arrests have risen, many residents and companies have fled. Indeed, indicators ranging from softening property rents to falling retail employment suggest the city has been losing its luster as an attractive place to live ever since its political crisis really took off in mid-2019, although it’s difficult to tease out the impact of the coronavirus pandemic.

At the same time, even though Hong Kong has lost some workers and businesses, its key financial services sector is holding its own as it becomes increasingly integrated into the Chinese economy and financial markets. Most importantly, the figures suggest Hong Kong’s stock market is becoming more and more dominated by Chinese stocks. Mainland stocks now make up more than 80% of Hong Kong’s stock market capitalization versus 57% a decade ago (see Figure 1). Mainland firms now account for almost 90% of all new equity funds raised in Hong Kong, counting both initial public offerings and follow-on deals. Mainland companies are also becoming ever more dominant in terms of the number of listed firms, new listings, and daily turnover on Hong Kong’s exchange.

Figure 1.

In the coming months and years, we think investors will increasingly see Hong Kong as “just another Chinese financial center,” like Shanghai and Shenzhen. For the time being, Hong Kong’s stock market will continue to have unique, attractive features compared with those two mainland exchanges, including its deeper liquidity and time-tested regulatory regime. That should temporarily preserve Hong Kong’s role as an attractive investment gateway into China (northbound trades from Hong Kong to Shanghai and Shenzhen now make up more than 81% of the “Stock Connect” program linking the stock markets). All the same, it will be increasingly clear that China is molding Hong Kong into its own likeness across multiple dimensions, which could ultimately make Hong Kong look less attractive as an investment destination.

Issue #3: China and Inflation

Money provides three functions—it acts as a medium of exchange, a store of value, and a unit of account. The first two functions, in terms of policy, are in opposition. As a medium of exchange, we tend to want more money supply. The greater the level of money supplied, all else held equal, the more one can buy. However, as a store of value, one would prefer the value of money to increase over time. Those with authority over money have to manage this internal contradiction. If they allow the supply of money to exceed the supply of goods and services, it could erode the store of value of the currency. On the other hand, fixing the supply of money can lead to deflation if goods and services increase.

There is no right or wrong answer to this issue; in fact, the decision is political in nature. Favoring the medium of exchange function supports debtors and industry, while favoring the store of value function supports creditors and finance. Of course, the issue is complicated by the role of credibility; if the monetary authority is considered a protector of the value of the currency, it can get away with supporting higher money supply levels without triggering inflation. In fact, monetary stimulus with credible monetary authorities can lead to a boom in financial assets if households believe that price increases won’t be allowed to fester.

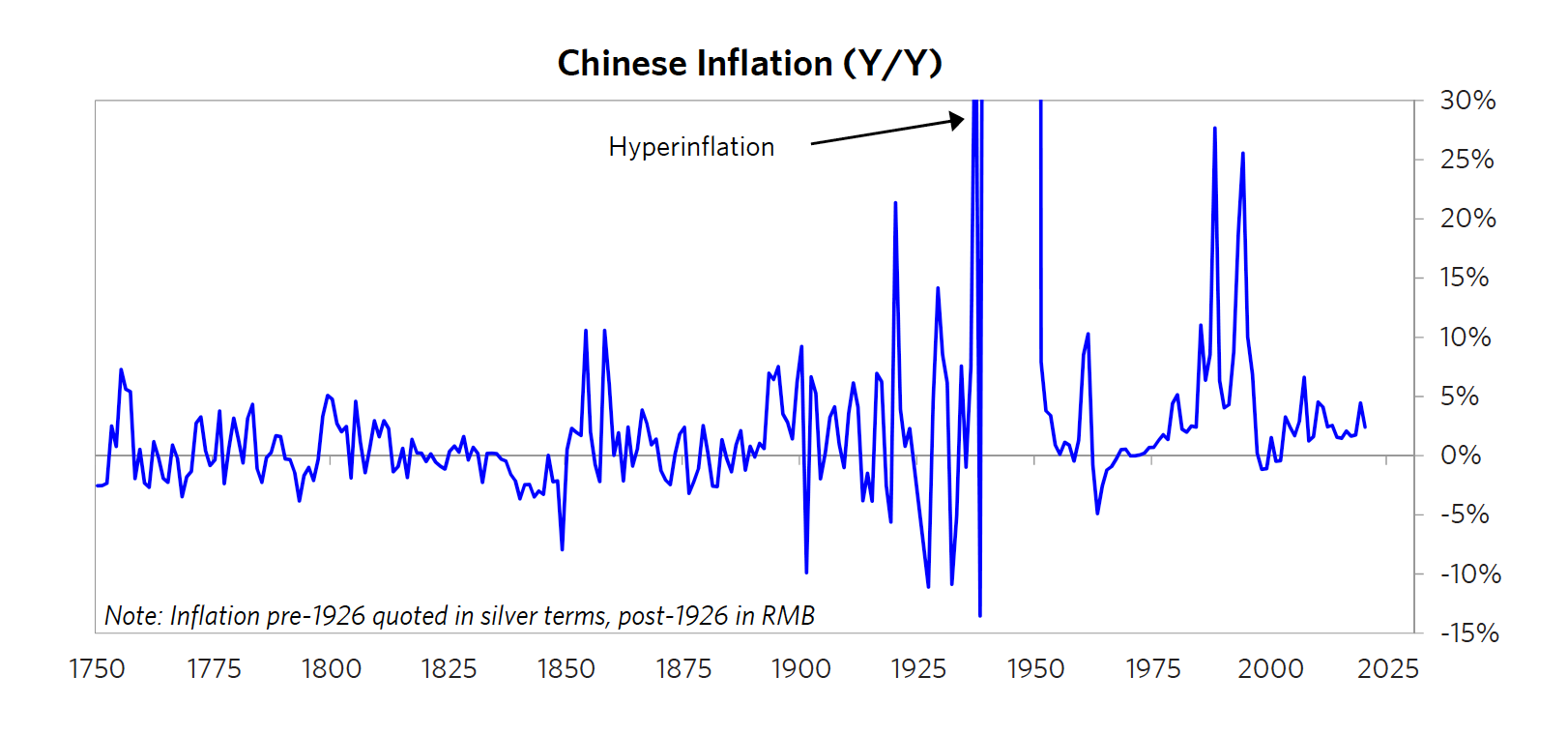

Since money is ultimately a social construct, the policy decision on inflation is political. China, given its long history, has seen episodes of inflation. Inflation was rampant under the Nationalists during WWII. For example, in June 1937, the CNY/USD exchange rate was 3.41. When the U.S. entered the war against Imperial Japan, the exchange rate weakened to 18.9 per dollar. By the end of 1945, it fell to 1,222 per dollar. By May 1949, it had fallen to 23,280,000 per dollar. Although inflation wasn’t wholly responsible for the Nationalist loss to the Chinese Communist Party in the Chinese Civil War, it weakened the popularity of the Nationalists and clearly didn’t help their cause.

Figure 2.

This chart (Figure 2) shows the hyperinflation during the war years. Inflation declined after Mao took control, with the exception of the Great Leap Forward in the late 1950s/early 1960s.

Figure 3.

Figure 3 shows Chinese inflation since the mid-1980s. The three spikes from 1985 through 1995 were mostly due to the conversion from a Marxist command and control economy, which had widespread price controls. The spike in the late 1980s occurred prior to Tiananmen Square and is thought to be partly to blame for the protests. Since then, market reforms, especially to the state-owned sector (SOE), have mostly kept inflation at bay.

Inflation is a policy choice. Inflation tends to benefit debtors and can act to spur economic growth as long as it doesn’t accelerate excessively. Deflation, on the other hand, benefits creditors. Societies tend to try to find a balance between the two, which usually results in modest inflation; the current consensus is about 2% per year. At the same time, narratives from national experience affect the degree of inflation tolerance. Germany’s experience of hyperinflation in the 1920s and the rise of Nazism in the 1930s led to a well-known anti-inflation bias. What may be less appreciated is that China likely harbors a similar position. For the CPC, the Nationalists’ inability to control price levels coupled with the inflation that preceded the Tiananmen Square event are a warning that inflation must be contained to hold power and contain social unrest. This means that China may end up resembling Germany in its inflation position; as China opens up its financial markets to foreigners, we could see China taking the role that Germany played in the late 1970s, especially if the U.S. opts for higher inflation.

Quick Hits

This section is a roundup of geopolitical issues we are watching that haven’t risen to the level of concern described above but should be monitored. Some of these issues may be topics of future WGRs.

- Biafra, Nigeria, social media, and rising civil strife.

- The continued tensions between Spain, Morocco, and Western Sahara.

- Drought, food prices, and geopolitical instability.

- The U.K.’s post-Brexit effort to recast itself as a global trading powerhouse by signing new free-trade deals

- Italy’s crucial test of whether it can make good use of the EU’s pandemic relief funding to transform its economy, which in turn could help revitalize the EU.

- Growing efforts by the private sector and governments to take advantage of big data.

Ramifications

Concerning Issue #1, the potential ramifications are broad. If the U.S. practices hegemony as earlier hegemons did, America might put trade barriers in place that will increase the cost to foreigners of acquiring dollars. This condition may lead to tariffs and quotas, restrictive trade arrangements (bilateral instead of multilateral), and perhaps currency manipulation. It is conceivable that the U.S. would force down the value of the dollar to reduce the value of foreign reserves or force foreign firms to either cut their profit margins to maintain market share or face the loss of competitiveness. If the U.S. plays a geopolitical balancing role, foreign nations will need to build their militaries, which would support defense contractors.

With Issue #2, the relentless integration of Hong Kong into the Chinese mainland financial system is especially important for investors. Ever since China entered the World Trade Organization in 2001, Hong Kong has lost much of its status as a major manufacturer and gateway for traded goods flowing into and out of China. Leveraging its unique financial services infrastructure, light regulatory regime, free capital account, and strong rule of law, Hong Kong has instead become the gateway for international capital flows into and out of the mainland. As Beijing continues to clamp down on Hong Kong’s political and social life, it becomes more and more logical that it might eventually restrict its commercial and financial structure as well. That’s especially true considering Beijing’s recent crackdown on mainland “fintech” firms over their growing influence and the risks they present to the mainland’s financial stability. For now, Hong Kong continues to offer an attractive venue for foreign investors to gain exposure to the Chinese economy, and for Chinese investors to gain access to foreign capital. However, Beijing may eventually want to bring Hong Kong in line with the mainland’s economic and financial infrastructure, and that would likely make Hong Kong assets much less attractive.

Concerning Issue #3, China is likely to address inflation in a manner different than the standard orthodoxy. Usually, inflation is addressed in the short run by raising interest rates and perhaps fiscal austerity. Beijing struggles with these methods because they threaten economic growth. Instead, regulators tend to use “administrative guidance,” which means they force firms to restrain price increases (and see lower margins), engage in lending regulation, exchange rate manipulation, and the use of buffer stocks. Western investors must remember that China won’t always rely on market signals, especially when they conflict with political goals. Although relying on markets tends to be efficient, it can lead to outcomes that may be considered intolerable to the CPC. For example, in the face of rising commodity prices, the CPC is more likely to use currency appreciation and buffer stock sales to contain price increases. Such behavior may be more bullish than normal for commodity producers because consumers won’t be seeing higher prices, the usual result of scarcity. And that action would maintain demand. At the same time, assuming high debt will “always” lead to crisis may not apply in the same way to China. The country can’t avoid dealing with the debt, but, in a totalitarian society, it has more power to assign the losses than in a democracy. If China is intent on keeping inflation at bay for social and political stability, its methods may surprise Western investors expecting a different outcome.

However, if China decides it wants to internationalize the CNY and it takes on a narrative of strict inflation control, Beijing could find itself in a position similar to Switzerland and Germany in the 1970s. The currencies of these two nations came to be seen as the world’s “hardest” currencies and appreciated rapidly. In fact, Switzerland applied a negative nominal interest rate to foreign accounts by the late 1970s to discourage further CHF appreciation. If a similar situation develops to this historical analog, it could mean the CNY would be poised to appreciate significantly in the coming years.

[1] Europe, the Far East, and the Middle East all have historic underlying conflicts. Specifically, Europe has never adjusted to the establishment of Germany as a state, and in the Far East, China and Japan have fought periodic wars for centuries. In the Middle East, colonial powers created pseudo-states that fulfilled their colonial aspirations but did not create workable nations. The current problems in that region are more about sorting out more natural states.

[2] This is why General Secretary Xi appears to be a man in a hurry.

[3] For a deeper view, see our WGR series from 2018, “The Malevolent Hegemon: Parts I, II, and III.”

This report was prepared by Bill O’Grady and Patrick Fearon-Hernandez, CFA, of Confluence Investment Management LLC and reflects the current opinion of the authors. It is based upon sources and data believed to be accurate and reliable. Opinions and forward-looking statements expressed are subject to change without notice. This information does not constitute a solicitation or an offer to buy or sell any security.

Confluence Investment Management LLC

Confluence Investment Management LLC is an independent Registered Investment Advisor located in St. Louis, Missouri. The firm provides professional portfolio management and advisory services to institutional and individual clients. Confluence’s investment philosophy is based upon independent, fundamental research that integrates the firm’s evaluation of market cycles, macroeconomics, and geopolitical analysis with a value-driven, company-specific approach. The firm’s portfolio management philosophy begins by assessing risk and follows through by positioning client portfolios to achieve stated income and growth objectives. The Confluence team is comprised of experienced investment professionals who are dedicated to an exceptional level of client service and communication.