South Africa has been prominent lately for two very different reasons. First, a political crisis that went on for too long finally ended with the resignation of the president on February 14th. Second, a major water crisis affecting its second largest city, Cape Town, which threatens to leave households without water supply this year.

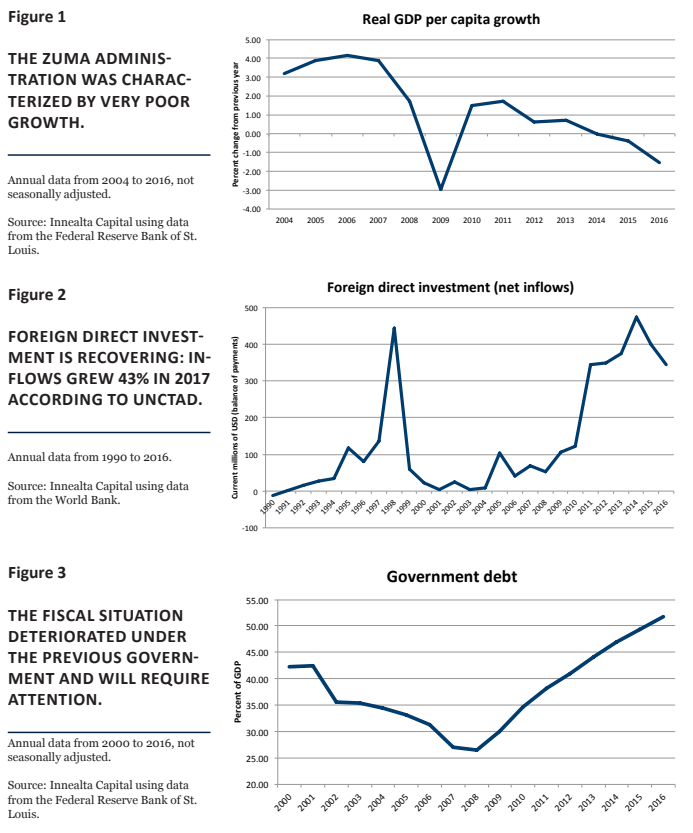

The country had to endure more than eight years with Jacob Zuma as president. The result was economic deterioration, political fragmentation, the weakening of public finances, the gutting of important public institutions, the looting of important state assets, corruption in the assignment of government contracts, and the downgrade of the country’s debt to junk status.

In sum, a disastrous administration that came to an ignominious end in February of this year.

Cyril Ramaphosa was appointed as new president. In spite of the challenges he will face, we believe Mr. Ramaphosa’s ascent to power to be a positive event for South Africa. The widespread corruption that was taking hold of many institutions had become a threat to South African democracy, and with that, to economic progress.

In the following paragraphs, we recount what went wrong in South Africa during the past nine years, and why we believe that a new administration is very good news for the future of Africa’s most industrialized economy.

Debt downgrade

On November 24th of 2017, S&P Global Ratings decided to downgrade the country’s rand-denominated debt to “junk” status, ending a process of deterioration that had started years before. The weaker-than-expected growth perspectives, the higher than-expected deficit projections and increased government debt, added to the political instability due to the uncertainty surrounding the next presidential election, motivated the move by the ratings agency. As expected, the rand lost value, and a sell-off ensued as investor confidence plummeted. The fact that Moody’s decided to only place South Africa’s debt under review, instead of downgrading it, spared the currency from bigger losses.

Corruption

This was by far the most prominent problem of President Zuma’s tenure in office, and the one that sealed his fate. Accusations actually were leveled against him even before he was inaugurated, meaning he was a tainted figure from the start.

Jacob Zuma was elected president of the African National Congress (ANC) on December 18th, 2007. (He had already been Deputy President of South Africa from 1999 to 2005, when he was dismissed.) This meant he would be the ruling party’s next candidate for the presidency, which in turn meant he was very likely to win. Only ten days after ascending to the top of the party, he was indicted on 16 charges of racketeering, money laundering, corruption, fraud, and tax evasion. But the charges were dismissed in September of 2008 by a High Court judge who found them to be politically motivated. This led to the resignation of then-President Thabo Mbeki, who was accused by the judge of improper interference in the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA). However, the judge’s ruling would be later overturned on appeal.

![]()

Just before the election, all 16 charges were abruptly (and suspiciously) dismissed on April 6th, 2009. Exactly one month later, Jacob Zuma won the election to become South Africa’s fourth president. His first five-year term started that same month.

State capture

The term became popular in South Africa to describe the appropriation of public companies and government contracts. The president built a network of business people that provided funds to him, his family, or his allies. The political system became much more corrupt during his time in office. The most infamous case is the one related to the Gupta family, which, in a nutshell, allowed one of Zuma’s sons to profit immensely, in exchange for government contracts and other perks. It was even reported that the Gupta family had the finance minister removed in March of 2017, only to be replaced with a lackey.

This was a huge scandal, as the minister removed, Pravin Gordhan, was highly respected and seen as a bulwark against corruption. His replacement would only last a few days, given the uproar his designation caused. Mr. Gordhan estimated at the end of 2017 that between $11 billion and $15 billion had been “looted” from the state. Moreover, many key positions were filled with loyalists, harming the checks and balances needed for good governance, and gravely undermining public institutions and the public’s trust.

Political fragmentation and turmoil Politically, waters would not be calm. Major cabinet reshuffles in 2010, 2011, and 2012 did not help. A new political party, Economic Freedom Fighters, created by a former ANC member, would damage Zuma’s support. Furthermore, in March of 2012 the Supreme Court of Appeal delivered a major blow to Zuma, allowing prosecutors to challenge the decision to drop the charges against him. And in October of that same year, a public prosecutor started looking into upgrades to the president’s private home, which were paid with public monies. None of these accusations impeded Zuma from being reelected, handily, as head of the ANC in December of 2012. This paved the way for his reelection in May of 2014.

Resignation

The Constitutional Court ruled against President Zuma in 2016, ordering that he pay back part of the money used to enhance his private home. This probably was the beginning of the end, with calls for him to either step down or be removed by the ANC before his second term ended in 2019. Then came a 2017 ruling by the Supreme Court of Appeal reinstating the charges that had been dropped in 2009. The Court thus upheld the 2016 ruling of the High Court regarding this matter.

The final blow to Zuma’s presidency came in December of last year, when Cyril Ramaphosa was elected president of the ANC. This meant he would be the next candidate for president, and not the runner-up, President Zuma’s ex-wife. Had she won, President Zuma probably would have rest assured that no one would investigate him. Public and political pressure started mounting for him to resign. Impeachment procedures began to be discussed, until it became clear that the president would very likely be ousted by parliament. Before facing a ninth no-confidence vote in parliament, which he was very likely to lose, he tendered his resignation on February 14th of this year. Parliament appointed Cyril Ramaphosa to the presidency.

Water crisis

Besides political problems, Cape Town, the country’s second-largest city, has been facing a water crisis recently due to a severe drought (and lack of proper planning). Dam levels are at extremely low levels, and emergency water-restriction measures – plus water-saving campaigns – have been put in place in order to avoid the city’s taps from running dry. It was first estimated that would happen in April of this year, but “Day Zero” – as it is known there – has now been pushed to 2019.

The city will need generous rainfall during the winter in order to avoid its water supplies from reaching even lower levels.

Conclusion

After the disappointing results of Jacob Zuma’s administration, the future looks much brighter for South Africa and its economy under the government of Cyril Ramaphosa. On March 16th, it was announced that former President Zuma would stand trial for corruption, charged with the same 16 charges that were so suspiciously dropped before his first inauguration as president. This sends a powerful signal to investors about a return to the rule of law that was so gravely damaged during Zuma’s tenure as president. Moreover, the OECD recently revised its economic-growth projections for the country upwards, mostly because of increased investor confidence and the renewed political landscape. The organization has predicted a 1.9% expansion for 2018 and 2.1% for 2019. Private investments and trade should increase, and inflation should be tamed.

Although the growth forecast is lower than the projected 3.9% for the world’s economy (for both 2018 and 2019), it is definitely an improvement over the 1.3% expansion of 2017 (as reported by Stats SA). What’s more, S&P Global Ratings, which downgraded South Africa’s debt in November citing growth and fiscal concerns, said in January that the outlook for the country was “stable,” instead of “negative,” as it was in November. Increased investor confidence will mean more foreign investment.