By David Lovell, Managing Director – Head of Marketing

Geopolitical risk is rapidly rising in Google Search volume since the end of 2022. For a couple of decades investors have not really been given reason to worry about geopolitical events or even wars. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine awakened a long-dormant risk that appears to be a major driver in macro analysis for some time to come.

As 2023 unfolds, uncertainty is too high to make high-confidence projections. Predicting such things, like the psyche of Vladimir Putin, is difficult if not impossible, so prediction will not be attempted here. However, it is prudent for investors to consider a full range of potential outcomes from the current environment.

In this post, we’ll examine the two critical factors driving geopolitical risks and their associated potential ramifications: 1) War in Ukraine and potential conflict concerning Taiwan: 2) Shifts in the global world order with a presumably ascending China.

What will be covered?

- What is Geopolitical Risk?

- Current Risk Factors: War & Potential Conflicts

- Multi-Polarity & Shifting World Order

- Addressing Geopolitical Risk & Market Volatility

What is Geopolitical Risk?

Geopolitics is the study and predicting of the behavior of nations and governments by focusing on the intersection of geography and power. Originally a term coined by the Swedish political scientist Rudolf Kjellén about the turn of the 20th century, the use of geopolitical analysis spread throughout Europe in the period between World Wars I and II (1918-39) and came into worldwide use thereafter.

The essential premise of geopolitics is that a nation or state will always pursue survival and power within the limits of geography, and further, most of its behavior will be driven by these basic instincts, whether conscious or not. The behavior of nations may impact a localized area, a region, a continent, or the entire globe. Geopolitics is more than a consideration of ‘global politics’, it is a descriptive and objective tool used to inform decisions about policies, investments, and even moral issues.

Geopolitical risk is the influence of geopolitical factors on markets, such as election outcomes across the world, military actions, or trade agreements. In an increasingly interconnected world, and given the speed of information today, geopolitical factors have great potential to move markets and investors therefore must take geopolitical developments and their associated risks seriously.

Changes in the geopolitical landscapes can increase uncertainty about future investment performance. It is important to note, not all geopolitical factors increase market volatility, and in fact, some factors can impact markets asymmetrically, making certain investments more attractive while negatively impacting others.

What Geopolitical Risk Factors Are Dialing Up Uncertainty?

Now, after decades in which investors had little concern for geopolitical risks, this particular type of investment risk is rearing its ugly head again as a prominent factor in macro analysis.

Several key simultaneous geopolitical developments are adding complexity to risk assessments and clouding potential outcomes for investors. Principally those developments are military and economic in nature.

War and Potential Conflicts: Ukraine War & Taiwan Tensions

War and the threat of war are the primary geopolitical developments that can upset markets. War is hard to predict. An errant missile or misunderstood posturing at the wrong place and time can change the course of history (e.g. WWI). Again, predicting is not the focus here. Instead, we’ll focus on the conditions escalating uncertainty around the principal conflict at hand and the next potential geopolitical clash.

Ukraine War: Obviously, as the war grinds on, the devastation manifested directly and indirectly within the fighting zone and surrounding regions increases, as well as, the resulting strains on global supply and commodity prices persist.

But with no end in sight, risks of catastrophic consequences for wider conflict intensify as well. Intelligence reports indicate that Putin may become more desperate, increasing the risks he leverages nuclear weapons as a negotiating tool or worse:

-

- Munitions are running low after more than a year of fighting. Ukraine is being replenished with munitions and upgraded weapons by the West, the U.S. in particular, while Russia is not, triggering concerns over nearby stores and weapons depos, like in Transnistria and Moldova,

- Starting in late 2022, Russia ‘activated’ nuclear ICBMs, and making ready the Yars nuclear missiles that are capable of hitting the U.K. and the U.S.,

- As recently as March 25th, 2023, Putin moved tactical nukes into Belarus.

This reckless brinkmanship may or may not result in nuclear arms detonation, but it certainly exacerbates the uncertainty and risks associated with a prolonged war on NATO’s doorstep. Not to be forgotten, the expansion of NATO with the addition of Finland and NATO comments about adding Ukraine expands that doorstep.

Meanwhile, China’s recent support for Russia in the Ukraine war has many in the West and Ukraine’s president concerned for WWIII. While the war in Europe has impacted global markets for over a year, the risks associated with a prolonged or escalated conflagration in this arena could be far more impactful than we’ve seen to date.

Taiwan Tensions: One war with broader global ramifications is enough for investors to contend with, but two conflicts involving global powers, and all that such a possibility entails, must also unfortunately be considered. China’s posture and rhetoric have become more aggressive towards Taiwan over the past few years, despite President Biden indicating the U.S. would respond militarily to any attack by China.

Often wars begin when there is a lack of clarity or miscalculation by one actor concerning the expected responses from other actors. The lack of international response to the Chinese annexation of Hong Kong, a debacle that was the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan, coupled with mixed messages and ‘walk-backs’ from U.S. State Department officials perhaps strengthens President Xi’s resolve to pursue the One-China policy.

The ramifications of war in and around Taiwan, beyond the fighting itself which would undoubtedly be devastating, are likely to be more disruptive to markets than the war in Ukraine has proved to be. Taiwan is the dominant manufacturer of computer chips, the lifeblood of our modern digital, interconnected world. Just as China’s COVID lockdowns crippled supply global chains, a war in this region and the potential trade dislocations among China and its allies versus its foes would significantly damage global markets.

The potential for major simultaneous wars on two continents is hard to quantify, but it is a real geopolitical risk nonetheless.

Multi-Polarity & A Shifting World Order

Since WWII, the world has operated in a unipolar framework. The Bretton Woods system established a world order in 1944, with the U.S. at the top supported by its new global reserve currency status. This “International Rules-Based’ Order, and its grip on the world, appear to be waning.

Many demonstrable events and new alliances signal a shift from a unipolar world to a multi-polar world—a new power paradigm with widespread geopolitical manifestations. Throughout history, many shifts in the “global order” have occurred. Ray Dalio, famed billionaire investor and hedge fund manager, explains the process behind and ramifications of historic changes in the global world order in this expertly crafted animated video.

Markets hate uncertainty. A new global power paradigm, by definition, ushers in uncertainty along with implications for global trade, currencies, power dynamics, peoples’ lives, and more.

China Rising: Intensifying Geopolitical Uncertainty

China’s demographic issues and financial market challenges are well documented. Opinions and prognostications around China’s demise abound. Nevertheless, ‘President for Life’ Xi Jinping and the CCP are playing the cards they have, determined to ascend to global superpower status. Despite a slow, costly global shift away from China as the ‘factory of the world’, the second largest economy remains the dominant global exporter of antibiotics and medicines, manufactured goods, batteries, solar panels, wind turbines, and other electrical equipment and machinery.

Whenever a nation vies for superpower status, geopolitical uncertainty intensifies vis-à-vis the existing superpower(s).

A rising China obviously threatens U.S. dominance and therefore poses massive implications for the markets and the existing world order. The developments over the past several years make it clear that China is positioning itself as the new superpower on many fronts, from trade and economic arrangements, to technology, to diplomatic and military leadership.

China’s deliberate strategy in pursuit of such aspirations is not new—they’ve been playing the long game. The One Belt and One Road policy (OBOR), underway for decades, is China’s long-term strategy to attain and then leverage deeper economic alliances and expand its geopolitical influence in Eurasia and across the globe. Initially, OBOR reached into Africa and Europe, but more recently China extended the program into South America and the Caribbean.

OBOR involves direct investment in infrastructure and trade arrangements in foreign nations, often with heavily subsidized Chinese companies at the center of the deals. That investment then provides leverage or strategic advantage over the participating nations or even nearby adversarial nations. For example, China’s government subsidies powered Huawei’s penetration into global markets—constituting more than half of EU country 5G networks. Over the years, many reports of data mining, IP theft, and espionage were leveled at Huawei.

Tik-Tok has become a global social media powerhouse, with over 1 billion users. Like Huawei, TikTok’s penetration is so large it has become a security concern for many countries, companies and government agencies; some have restricted or banned the app.

China has been deliberate, it seems, in the post-COVID era to initiate a shift in international alliances and trade agreements altering existing global power dynamics. By assuming the lead in dealmaking in the Middle East, China is seeking relevance and elevating its perceived potential as the new global superpower. This has major geopolitical implications, including suggesting a shifting the ‘global world order’ and the potential for replacing the United States as the assumed power broker in the region.

China has bolstered its position within the United Nations as well. It is now the second-largest contributor to both the U.N.’s regular budget and the peacekeeping budget. Chinese nationals head four of the U.N.’s 15 specialized agencies. China provides more personnel to peacekeeping operations than any other permanent member of the Security Council.

Since the Ukraine war broke out, China has been asserting itself in many diplomatic talks, often at the consternation of Western global leaders, in order to heighten or maintain influence. China recently held a historic diplomatic meeting with Russia—signing many agreements—during which Xi described Russia as an “unlimited partner”. For over 50 years, the United States successfully managed (and profited from) keeping these two powers at odds. A new Russo-Chinese alliance could create bipolar forces that realign the world, pulling and pushing other nations into choosing sides. Recently, Iran, Russia, and China began conducting joint military exercises.

Perhaps the most ominous and potentially unsettling for markets is China’s undeniable militarization of late. In October 2022, President Xi Jinping appointed a war cabinet and a month later reportedly directed the People’s Liberation Army to focus on preparation for war. For years, China has been closing the technology gap with the United States (often by leveraging U.S. technology), improving its military capabilities with:

- Hypersonic missiles,

- Passive targeting,

- drone swarms,

- quantum computing and cyber,

- 5th generation combat aircraft, and

- now the world’s largest naval force.

Recently, China has embarked on more brazen action. In February of this year, China floated multiple spy balloons over strategic locations in the U.S., including missile silos and air bases. Over the past two years, China bought over three hundred and fifty thousand acres of farmland, some in direct proximity to military bases, including a base responsible for America’s most sensitive drone technology.

Meanwhile, the U.S. military is increasingly focused on equity and climate change, while reducing recruiting standards and fitness requirements. The U.S. does not seem convincingly prepared to deal, directly or indirectly, with major global conflicts on two fronts—especially considering the Pentagon admits our munitions stockpiles are severely depleted and our strategic oil reserves (especially sour crude) are at their lowest level since 1984.

A shift from unipolar to multi-polar geopolitical alignments cannot be understated. Most obviously, when there are two opposing forces, conflict becomes more probable over time. Such a dreadful potential outcome is not one that investors may want to consider, but with history as a guide, the probability of some sort of major conflict should not be underestimated.

Implications of Multi-Polarity: Reserve Currency Impact

Beyond the possibility of international conflict, at a minimum, a shift to a multi-polar world increases uncertainty around global trade and power dynamics. In particular, a New Order could mean a threat to the dollar’s reserve currency status—a major issue, not just for investors but for the global financial system. This may not happen suddenly overnight, but perhaps the dollar would suffer a weakening by a thousand cuts.

Unprecedented sanctions and assets seizures by the West (led by the U.S.), in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, triggered other countries to seek ways to reduce their vulnerability to America’s financial reach. Representatives of many countries started to travel to Moscow and Beijing to form new alliances, new trade agreements, and new loyalties to replace the ever-riskier relationship with the United States.

This reaction to the “weaponizing of the dollar” as CNN’s Fareed Zakaria describes here, threatens the U.S. dollar’s status as the global reserve currency. BRICS+ nations are exploring baskets of currencies as an alternative to the dollar:

- Russia is already using yuan for international settlements;

- Russia shifting to Dubai benchmark in Indian oil deal;

- Brazil’s president calls for the end of dollar dominance in foreign trade, backs a BRICS currency, and recently struck a deal with China;

- The Bank of International Settlement, the IMF and World Bank, as well as, the Chinese are exploring multilateral international payment systems outside the dollar-dominated SWIFT system;

- India has been buying Russian oil outside dollar;

- China, India, and others buying Russian oil as the West boycotts Russian oil/gas and other goods

- Saudi Arabia considering the yuan for settling oil sales with Beijing;

- Malaysian and China are discussing an ‘Asian Fund’ to cut U.S. Dollar dependency;

- France and China completed the first cross-border Yuan settlement of LNG trade;

- Japan breaks with U.S. and Allies, and buys Russian oil at prices above cap.

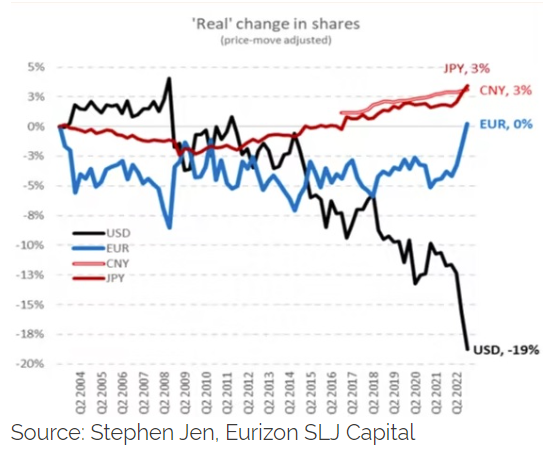

The share of dollars in global bank reserves has dropped steadily from over 70%, 25 years ago to less than 60% through 2021, according to the International Monetary Fund.

Stephen Jen – a very well-known currency analyst – recently quantified just how rapidly the de-dollarization is occurring. Jen, who was previously at Morgan Stanley and now runs money at Eurizon SLJ, warned in a recent briefing note, that the dollar is losing its reserve status at a faster pace than generally accepted as many analysts have failed to account for last year’s frantic swings in exchange rates.

If trust in and reliance on the dollar wanes further, so too may the benefits of the reserve currency status heretofore enjoyed by the United States.

Unprecedented spending without any concern over deficits appears to be eroding confidence in the dollar. The national debt had grown five fold over the last 30 years—from roughly $6.5T in Q1 2003 to $31.5T in Q1 2023—the result of exploding fiscal spending along with the Fed’s intervention and balance sheet expansion (from $738B in 2013 to over $8.7T in 2023). All of those historic increases were, of course, required to cover a series of financial crises, spurred by grift-driven fiscal malfeasance and entitlement expansion packaged by politicians as necessary amelioration.

All of this spending and debt accumulation remains inconsequential for the most part because of the dollar’s unique reserve currency status and the assumption there will always be buyers of U.S. debt. But what if that assumption does not play out, in the same way, going forward? In recent years, the two biggest foreign holders of US debt, Japan and China, have reduced their holdings of US Treasuries.

Fears over the loss of the dollar’s reserve status have existed since the 1970s. Today, many experts show little concern it could happen at all. On balance, it is important to remember the world is still chained to the ‘Master Dollar’. Thus, de-dollarization of the global credit-based system likely won’t happen fast, because:

- The U.S. remains the largest, most trusted market in the world with;

- between 70-80% of global invoicing and trades happen to be denominated in USD;

- roughly 60% of global reserve currency reserves despite being only about 25% of the global economy;

- and a willingness to maintain massive trade deficits.

Throughout history, the final catalyst for changes in the global reserve currency status has most often been a massively disruptive event (e.g. civil war or external foes). While this is not something to wish for, or to expect as a base case in anyone’s lifetime, historical precedence underscores the risks associated with potential conflicts with China and/or Russia.

Addressing Geopolitical Risks and Market Volatility

Uncertainty in Q1 2023 is too high to make high-confidence projections about the two critical geopolitical factors driving markets: 1) War in Ukraine and potential conflict concerning Taiwan: 2) Shifts in global world order with a presumably ascending China.

When global powers puff up their chests and tensions rise, risk management is paramount. Special attention is certainly prudent when considering the potential tectonic shifts in the global power order. Often, saber rattling results in little more than noisy headlines, and outcomes are rarely as bad as media talking heads on either end of the political spectrum may forecast, so it pays to remain always invested.

But international developments can unfold quickly, with markets moving even quicker, so it pays to be always hedged. While traditional portfolio construction relies on diversification across asset classes, and principally on bonds to mitigate equity market risks, nearly all asset classes fell in lock step in 2022. Moving to and/or remaining in cash invites significant timing risk, while inflation erodes the buying power of that cash. On the other hand, certain bond investments may present credit, currency, and liquidity risks in a debt or currency-related crisis.

After the ‘everything bear market‘ of 2022, when nearly every major asset class was highly correlated, investors are looking for alternative means to manage the risks associated with an increasingly tense geopolitical landscape.

Given the potential impacts of geopolitical upheaval on currency markets and a recent spike in inflation globally, it’s no surprise that gold has seen a strong bullish run over the last few years. Hard assets, like gold, silver and other precious metals for example, are popular tools for managing risk or hedging against massive currency market disruption and a tried and true inflation hedge. Cryptocurrencies, like Bitcoin and Ethereum, are on the rise of late as well given they exist outside the fiat currency system. Yet cryptocurrencies and the associated technologies are far more volatile than gold or silver, behaving much more like growth stocks, and their ‘mettle’ has yet to be tested as a true fiat alternative.

In the face of rising geopolitical tensions and the potential for global war, hedging with put options is a compelling way to mitigate risks to the broader equity market. Put options are inversely correlated assets, can be structured over various lengths of time, and certain options markets (e.g. SPX and SPY) are some of the most liquid in the world. Options-based hedged equity strategies may enable investors to remain in the markets and yet maintain a level of risk mitigation aligned with their risk tolerance and overall investment objectives.

Important Notes and Disclosures:

Swan Global Investments, LLC is a SEC registered Investment Advisor that specializes in managing money using the proprietary Defined Risk Strategy (“DRS”). SEC registration does not denote any special training or qualification conferred by the SEC. Swan offers and manages the DRS for investors including individuals, institutions and other investment advisor firms.

All Swan products utilize the Defined Risk Strategy (“DRS”), but may vary by asset class, regulatory offering type, etc. Accordingly, all Swan DRS product offerings will have different performance results due to offering differences and comparing results among the Swan products and composites may be of limited use. All data used herein; including the statistical information, verification and performance reports are available upon request. The S&P 500 Index is a market cap weighted index of 500 widely held stocks often used as a proxy for the overall U.S. equity market. The Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index is a broad-based flagship benchmark that measures the investment grade, U.S. dollar-denominated, fixed-rate taxable bond market. The index includes Treasuries, government-related and corporate securities, MBS (agency fixed-rate and hybrid ARM pass-throughs), ABS and CMBS (agency and non-agency). Indexes are unmanaged and have no fees or expenses. An investment cannot be made directly in an index. Swan’s investments may consist of securities which vary significantly from those in the benchmark indexes listed above and performance calculation methods may not be entirely comparable. Accordingly, comparing results shown to those of such indexes may be of limited use. The adviser’s dependence on its DRS process and judgments about the attractiveness, value and potential appreciation of particular ETFs and options in which the adviser invests or writes may prove to be incorrect and may not produce the desired results. There is no guarantee any investment or the DRS will meet its objectives. All investments involve the risk of potential investment losses as well as the potential for investment gains. Prior performance is not a guarantee of future results and there can be no assurance, and investors should not assume, that future performance will be comparable to past performance. Further information is available upon request by contacting the company directly at 970-382-8901 or www.swanglobalinvestments.com. 084-SGI-041223

For more news, information, and analysis, visit the ETF Strategist Channel.