By Michael Paciotti, CFA

“Speak softly and carry a big stick; you will go far.” – Theodore Roosevelt

Executive Summary

• With inflation continuing to press above 7% at the consumer level, markets are now pricing in an 83% probability of 6 or more 25bps rate hikes by the Fed in 2022, simultaneously imparting a steady, but cautious hawkish tone to investors. This somewhat complacent attitude may be due to the realization that an aggressive battle against inflation could have dire implications for financial markets and the economy through the portfolio balance and wealth effect channels.

• The wealth effect and portfolio balance channels are non-conventional mechanisms of transmitting monetary policy and come into play when the Fed drives interest rates to zero, causing investors to seek higher returns in = other assets and bidding up the price of those assets. Investors feeling “wealthy” harvest those gains and spend them into the real economy. Restoring the yield to safe assets has the potential to reverse this effect, hence the cautious approach.

• Inflation fighting is more about psychology/credibility then about actual action. If consumers feel that goods will be more expensive tomorrow, they accelerate purchases and in essence create the inflationary reality. As long bond yields rise to price in higher inflation, equity multiples typically fall sharply.

• Assuming that the Fed’s goal is to cool inflation without causing equity markets to tumble and a negative wealth effect to infect the economy, Jerome Powell would be wise to channel as much inner bravado as he can and act tough early to establish his inflation fighting credibility.

In the past several months markets have completely reshaped the inflation narrative from “transitory” and no rate hikes expected until 2023, to now pricing in an 83% probability1 of 6 or more 25bps rate hikes by December of 2022 (as of Feb 16th), taking the Fed Funds rate to 1.5%-2.5%. This has left some to speculate whether the Fed is behind the inflationary curve and, more importantly, if this is true, why?

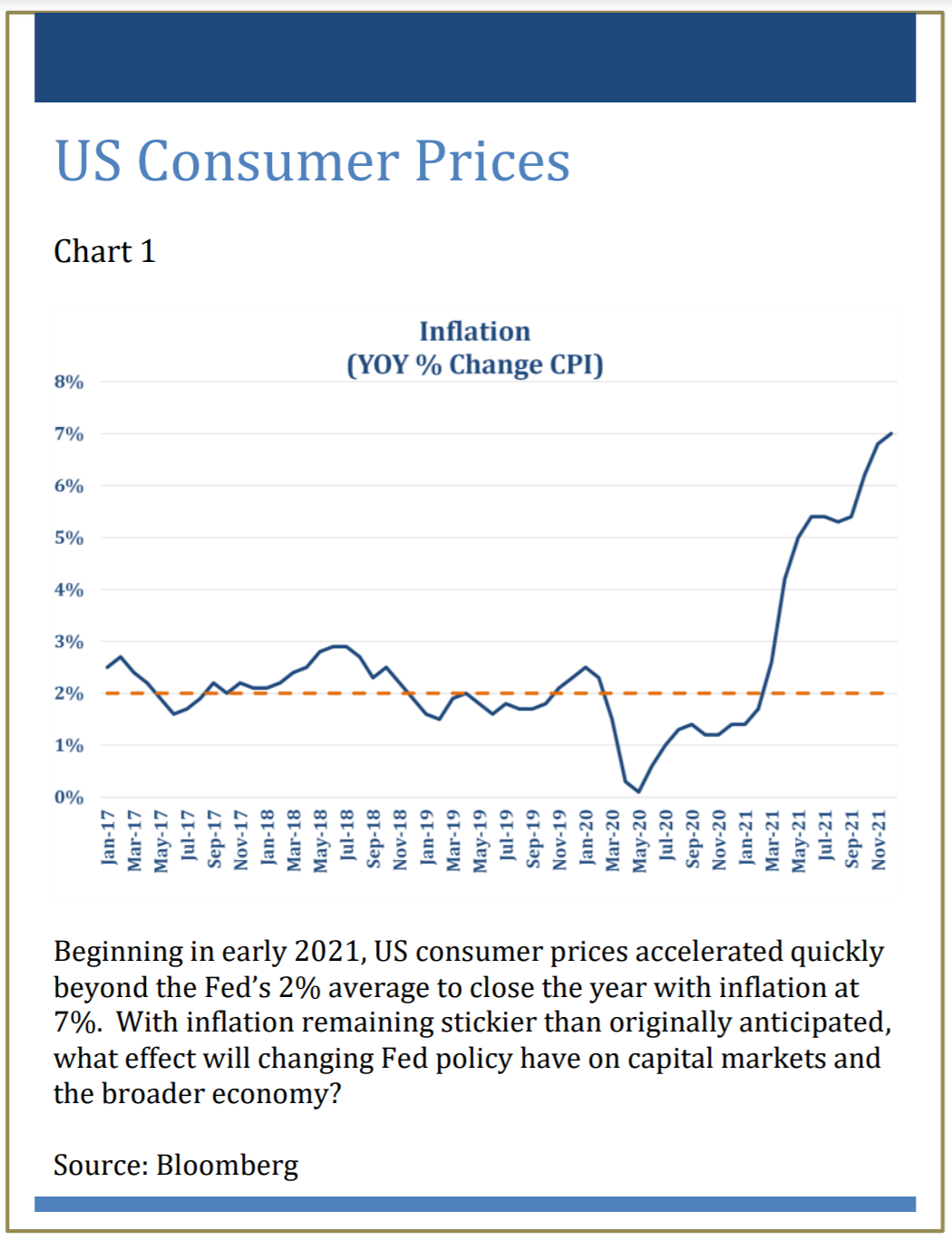

While supply chain disruptions may be to blame for some part of our current inflationary predicament, suffice it to say, Fed officials now seem poised to act rather than wait for these issues to resolve themselves. Chart 1 shows the increase in consumer prices on a year-over year basis since 2017, compared to the Fed’s “target rate” of 2%.

By early 2021, we can see that inflation had already returned to that 2% target level. However, Fed policy evaluates inflation via the average over time, where periods of above average inflation may be allowed to accommodate labor markets reaching full strength and to offset periods where inflation may have been below the average. By understanding the policy, this explains why inflation was allowed to move above target.

However, by May 2021, inflation had reached 5%, a level not seen since 2008, and 7% by year end. Even considering below average inflation from prior periods, the severity of the move above trend has become worrisome. Has the Fed misread the situation all along? I would argue that a small part of our current predicament may be attributable to that. Economic forecasting, especially over short periods, is a fairly daunting task, for even the brightest of minds that comprise our central bank. Throw in the unusual circumstances of the pandemic and its impact on our fragile supply chain and those errors can be compounded. I doubt, however, that is the primary reason. Rather, I would hope that they have been deliberately complacent, wishing that supply chains would normalize and naturally ease inflationary pressures, because they really have no other option. That is, they may recognize an aggressive battle against inflation risks dire consequences for financial assets, household wealth, and correspondingly the economy through the same channels that Ben Bernanke and his predecessors used to stimulate, the wealth effect and portfolio balance channels.

Why are the Wealth Effect & Portfolio Balance Channels Important?

Let me transition into our broader discussion by first proving some background information, which is important in understanding how the pieces fit together. The Fed can accomplish an economic goal of stimulating growth

though the normal interest rate channels or through quantitative easing (bond buying). This occurs by making people feel wealthier, so they spend more money and is accomplished by affecting the mix of assets they own, making safe assets unattractive via low yields and encouraging investors to buy riskier assets like stocks, bidding up the price of those assets. This stimulates through a lower cost of capital to companies, or by gains being harvested and spent. It works in reverse too. By restoring the yield to safe investments, this has the potential to draw capital away from risky assets by making safety more attractive. It is my belief and hope that the Fed knows this, and as a result they recognize that they are toothless in this fight. It would seem then, via their ever-so cautious approach amidst accelerating price levels and supply chain issues that appear somewhat longer tailed, they recognize they can’t be aggressive or risk toppling the house of cards they have created. Hence the slow pace in responding.

If it is in fact the case that the Fed finds themselves relatively defenseless in this fight, what should they do? One option is they can do what they are doing now…speak softly, but proactively on the looming inflation issue and hope to convince the market that 1.50% of policy tightening is enough to conquer 7% inflation. It isn’t, and they know it. How could it when they themselves describe “normal policy,” defined as neither accommodative nor restrictive, as a Fed Funds rate of 2.5%? Their foot is still firmly on the gas at 1.50%. By carefully choosing their words, so as to not shock the system into believing an overly aggressive stance, will inevitably result in a policy error…and I would argue that the careful, methodical, deliberate approach, is the exact policy error they seek to avoid. You see, when you carry a big stick, you can speak softly. When you carry no stick, you better speak loudly enough to make them think you carry a big stick. This is a key component of inflation fighting, psychology and credibility, that we’ll come back to momentarily.

A Little Fed History

The modern form of monetary policy (not to be confused with modern monetary theory) can trace its routes back to the 1970’s Federal Reserve. At the time there was some debate around not only if the central bank could control inflation, but through what variables and at what cost to the economy. In fact, at one point it was estimated that a 1% reduction in inflation would come at a 10% cost to labor markets for a decade!

In what I will call the early days of the modern central bank approach to policy, the Fed struggled, meandering through a decade of “go-stop” monetary policy where the Fed would stimulate or tighten based on the prevailing public perception of unemployment or inflation. When the primary public concern was rising prices, they would tighten. When job concerns took center stage they would stimulate. This whipsaw policy became easy to game during the “go phase”, causing job seekers and distributors of goods and services to aggressively ask for higher wages and prices during the green light portion of the cycle. Given that wages are the primary input cost to most production, it is not surprising that inflation accelerated and was the predominant problem for the era. To compound things, the era saw the end of the Breton Woods system of fixed exchange rates, where all currencies were anchored to the dollar at a fixed rate, which was in turn convertible to gold at $35 an ounce. This link limited the ability of nations to add to the money supply. With the collapse of the system, currencies were allowed to free float, creating ample flexibility around money creation. Since long-term inflation or deflation is almost always associated with a shift in the money supply, this caused additional inflationary pressures. Lastly, when we also consider the supply disruptions of the time, in the form of oil shortages, we have all of the ingredients for a highly inflationary decade and that is exactly what we got.

Perhaps one of the most important and not often discussed elements of shaping our modern approach to central bank policy is the work of Robert Lucas and Thomas Sargent. Lucas and Sargent showed that perhaps the most important variable in influencing inflation was psychology and inflation expectations. If one is credible in their show of force against inflation, it shapes market psychology around prices and, in and of itself, accelerates or reduces inflation based on the direction of the credible threat. Said differently, one of the most powerful forces in creating inflation (or deflation) is the belief that prices will be higher (lower) tomorrow and perhaps significantly so. Once this mindset sets in, it encourages buyers to consume more today to benefit from the current lower price. This alone creates inflation. The reverse is also true. If buyers believe prices will be lower, they will delay purchases, causing producers to lower prices to stimulate demand. The psychology is essentially a self-fulfilling prophecy.

In the aftermath of the 1970’s inflation era, it took Paul Volker to establish inflation fighting credibility. With inflation peaking at 14.8% in early 1980, Volker raised the Fed Funds rate to 20% by 1981(10% in one year alone) amidst some of the fiercest political attacks and criticism in modern history. Because Volker was undeterred by this criticism, it established the credibility necessary to stop inflation. While this is a nice history lesson, there are several important points that we can learn that relate to today. Perhaps most important among them was as Volker sought to establish this credibility, the market tested him. In early 1980, the 30-year treasury jumped 2% in just 2 months, reflecting an inflationary scare. This happened again in 1981 with yields on the long bond rising 3% from January through October of 1981. When the Fed fails to establish enough credibility, long bond yields rise, as they did in Volker’s early days. This is important given my prior question on rates and inflation, which I’ll repeat…In an environment of 7% inflation like we have today and a neutral Fed Funds rate of 2.5%, how likely is it that 6 rate hikes in 2022 (150bps) is enough to combat inflation? Once tightening starts, if we continue to see stubborn inflation, I suspect Jerome Powell may experience a bit of what Volker did, long bonds rising, as the markets challenge his credibility or lack thereof.

Slow and Steady won’t Win this Race

I’m all for measured and methodical in most instances. Not this one. Allow me to illustrate why. First, let’s assume the objective is to fight inflation in a manner that does not disrupt equity markets, thereby spilling over into the real economy and causing both recession and job losses. Probably a safe assumption. I mentioned previously that the stated neutral rate of Fed Funds is 2.5%. Even considering a very deliberate path of 25bps across 6 intervals, that gets you to 1.50% on Fed Funds, half the stated neural rate. Technically, they are still stimulating at that level.

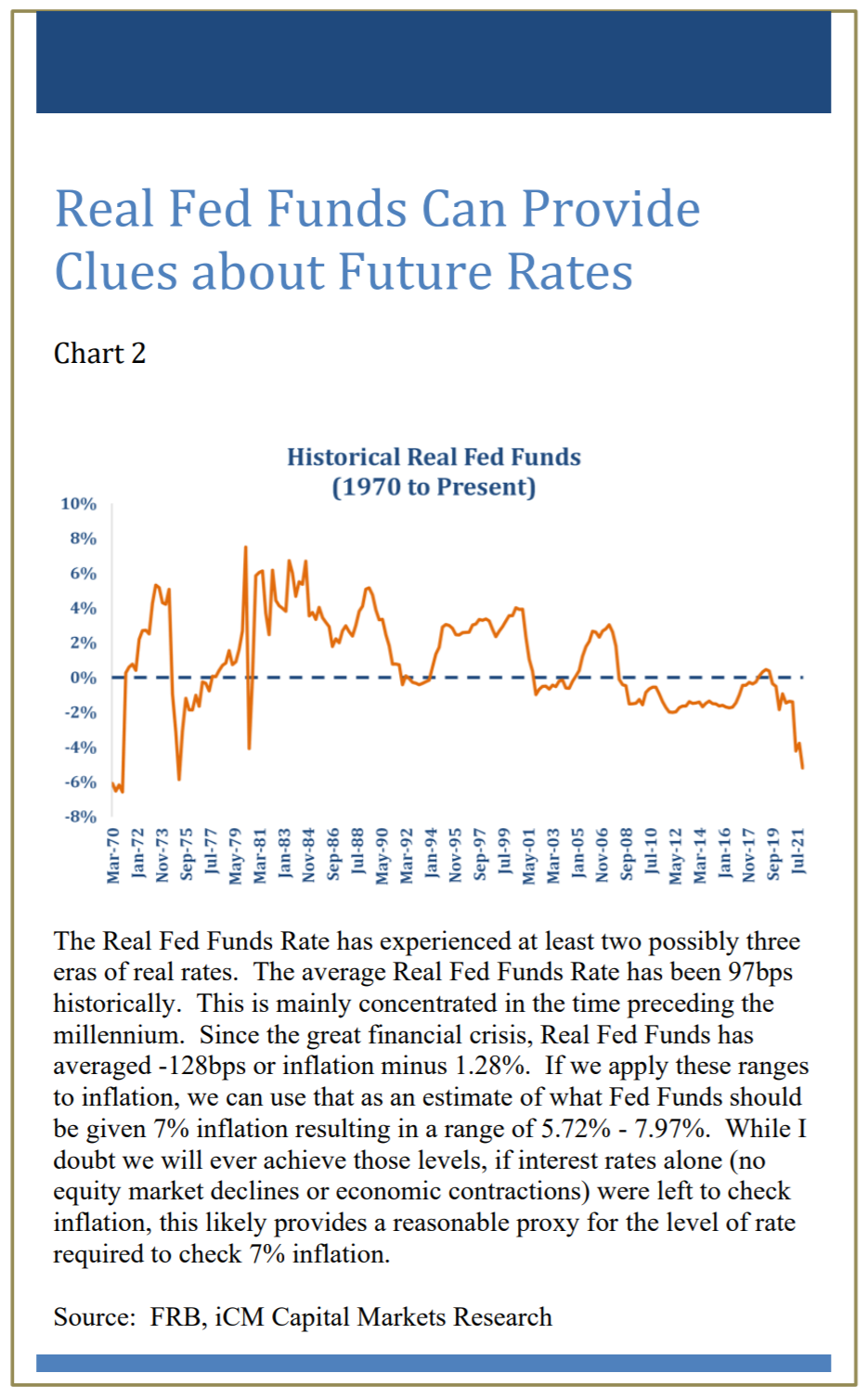

Beyond that, a simple approach to estimating the neutral Fed Funds rate is known as the Taylor Rule. Now, the Taylor Rule is not without criticism. In fact, I will state up front that I doubt that we will ever get to the level of rates suggested by the Taylor Rule or my second methodology, Normal Real Fed Funds Rate, but I mention both to illustrate where rates should be if left to do all the lifting on their own. The Taylor Rule is a rather simple framework to estimate what Fed Funds should be given what the level of current economic growth and inflation are compared to what expectations are for each in the long-run. If we apply this formula, we find that at 5% real GDP and Core PCE inflation of 4.85% (vs LT averages of 2% respectively) we arrive at an implied Fed Funds rate of 6.5%. Outlandish…yes. But let’s keep drilling down on this.

My second method is again a very simple approach. What is the normal real or inflation adjusted Fed Funds rate? We then apply that premium to current inflation for an estimateof what the Fed Funds rate should be today. Since 1970, the Fed Funds rate has resided about 1% above the level of inflation (97bps to be exact). As we can see in Chart 2, this data is greatly skewed with high real Fed Funds rates leading up to the millennium and mostly negative real rates since the Great Financial Crisis. If we apply the overall average of 97bps, today’s implied Fed Funds rate should be 7.97%, higher than the Taylor Rule if we use the overall real Fed Funds average. As seen in Chart 2, more recently the “new normal” has been – 128bps or 5.72% implied Fed Funds. Still significantly higher than where we are today. I conduct this exercise not to illustrate where I think we will arrive, but to show the level of Fed Funds necessary absent any other variables assisting, to sufficiently counteract inflation on its own. Again, let me say I doubt that we will ever get there. It would either require a lengthy cycle of gradual hikes, in which case this will allow enough time for the supply chain to normalize, or if forced to hike aggressively, equity

markets would likely fall and inflation with it, due to the negative wealth effect. As investors, we all hope it’s not the latter.

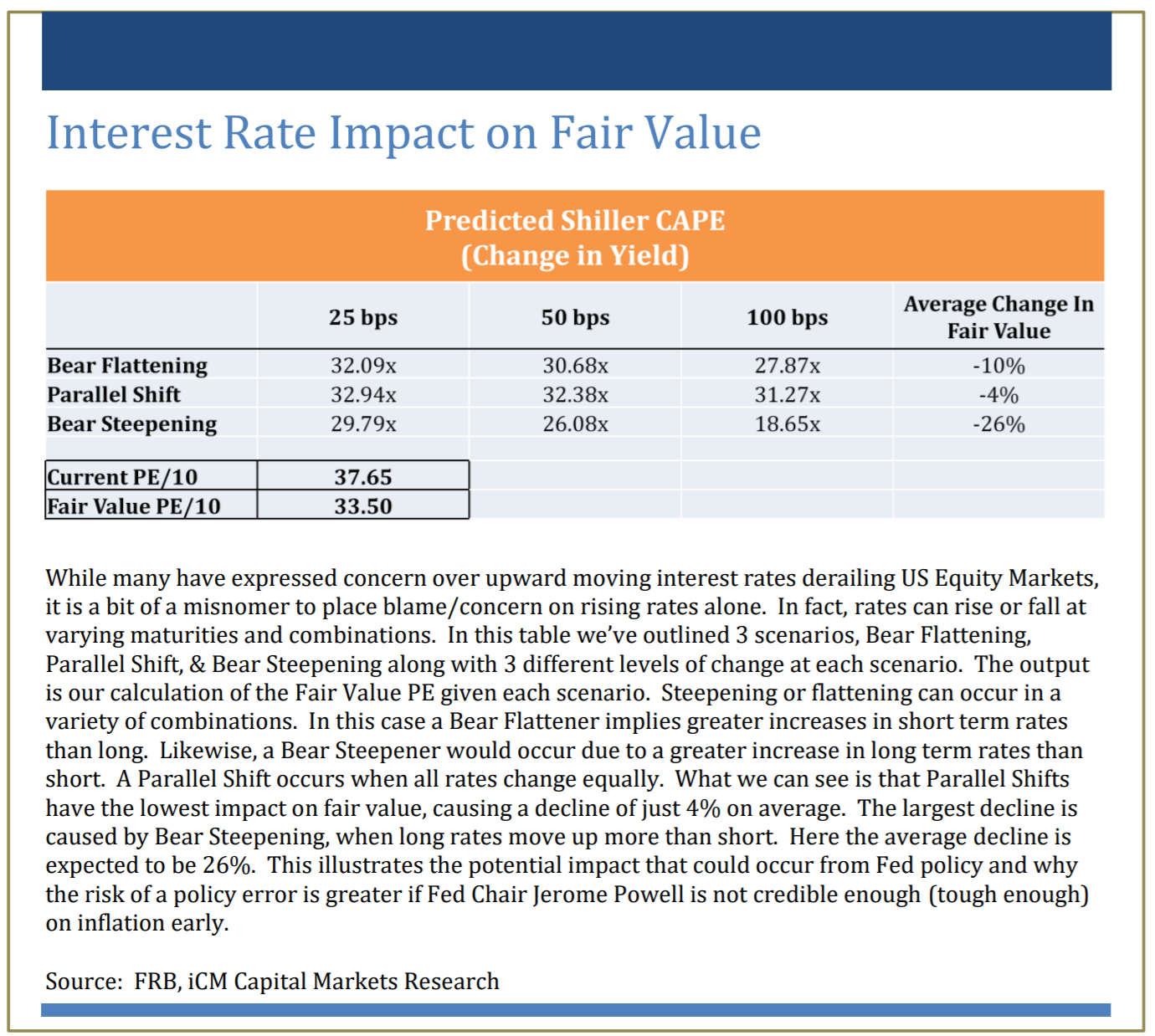

So, what are the risks? As I’ve stated many times previously, interest rates have a disproportionate effect on equity markets, depending on where the movement in rates occurs (short-, medium-, or long-term rates) and how it impacts the shape of the yield curve. Simultaneously, rate movements do not impact all equities equally, with growth stocks and generally other low yielding segments being more interest rate sensitive than value stocks or higher yielding segments.

For simplicity, let’s focus on the broad impacts to US equities. As I’ve stated before, investors seem to be hard wired to focus on the level of interest rates, assuming with a blanket statement that any upward movement in rates is bad for stocks. For this exercise I will offer our own interest rate model, whereby we predict the cyclically adjusted PE or CAPE for US large cap stocks via the slope and yield of the curve. For those statistically inclined, the model explains about 80% (r-squared) of the change in the CAPE via the level and slope of the yield curve, with all variables exhibiting high statistically significance. From last year at this time, clearly inflation expectations have increased and rates along with it. The 2-year treasury was priced to yield 0.12% in February of 2021, today its trading at a yield of 1.50%. At this time last year, the model indicated the S&P 500 should be priced at a CAPE of 27x trailing ten-year earnings. In reality, the market was actually priced at 35x. The way to interpret this is that the market was overvalued by about 30%, given the level of rates and slope of the curve. Despite the increase in rates at the 2-year, markets have actually done quite well, with the implied PE today sitting at 33x, meaningfully higher than it was a year ago despite the increase in the 2-year. Why? While the level of rates at the 2-year increased by 138bps in the last year, 10-year bond yields increased by only 76bps. The curve flattened.

What we are observing is that slope is meaningfully more important to valuations than the level of yields. For example, if I were to shock yields at the 10-year level by adding 1%, holding everything else constant, the implied valuation should be 18x, a decline of 45%. If I increase the yield on the entire curve by 1%, the implied fair value falls by only 25%, as opposed to a 45% decline under the steepening scenario. So, what I would suggest is that its meaningfully more important to focus on the shape of the curve than it is the level of rates. Again, stocks gained over the past year as rates rose, but the curve flattened. We are unlikely to be so lucky if/when long-maturity bonds also rise. The scary part of this is that I think we are facing a scenario where this is not only possible, but likely to occur. Just as the bond vigilantes tested Volker’s inflation fighting credibility, they are likely to test Jerome Powell. That test will come when markets begin to believe he either lacks the conviction to raise rates sufficiently, if faced with the pressure of a declining equity market and recession. As a result, long yields will likely rise to price in inflation that is higher and more permanent over the long-term. While this may or may not be temporary, it will likely be disruptive and painful.

To conclude, it’s been some time since we’ve actually had to deal with an inflation problem in the US. The disinflationary pressures we’ve dealt with for the last 20 years have now succumbed to factors originating from the pandemic, supply chain disruptions and more money chasing fewer goods and services. It will dissipate and we will again, sometime in the future, be talking about deflation. This I’m sure of. It may not be immediate, perhaps a few years in the future, but it will happen again. For this portion of the cycle, we expect the most interest rate sensitive sectors, those that benefitted the most over the last few years, will likely be hurt the most. We own little of these assets and, as a result, have fared well thus far. It is also our expectation that rates will never approach the levels suggested by the Taylor Rule or Normal Real Fed Funds Rate methods. Before that happens, supply chains will normalize, we will slide into a recession, or equity markets will fall creating a negative wealth effect, dousing inflationary fires with cold water. Perhaps all three.

To avoid this, if it is avoidable, I argue that psychology is not only the Fed’s most important weapon, but perhaps their only weapon of any potency. The psychology of inflation raises another rather interesting question. Is the inflationary animal (psychology) that we are trying to tame a different animal than the animal spirits Alan Greenspan used to describe equity market gains? I suspect that animal spirits for risk assets and inflationary psychology are the same animal. I’m not sure it is possible to sufficiently dampen inflation without simultaneously crushing investor enthusiasm and bringing the equity market multiple down several turns, although I’m hopeful. To do this I anticipate that Fed Chair Powell must channel as much bravado as he can muster and bluff…hard, if he is to dampen inflation long enough for the supply chain to resolve itself. I hope that by beginning with a show of force, theoretically he may need to hike less. If not, what is his resolve when he is 150bps into his campaign, inflation is still 7%, and the market is down 30%? This only he can answer. To prevent this, he needs to keep the curve flattening, which to date he has been successful at doing. Once the market realizes that his actions aren’t enough and that he isn’t carrying a big enough stick, or one at all, the curve could steepen by the long end moving up to process in higher inflation in the future, in a similar manner to the market’s tests of Volker. This is the crusher for multiples. We haven’t gotten there yet and hopefully we won’t. Thank you as always for your continued trust and confidence.

Fed in Focus – Speak Loudly When Carrying No Stick is intended solely to report on various investment views held by Integrated Capital Management, an institutional research and asset management firm, is distributed for informational and educational purposes only and is not intended to constitute legal, tax, accounting or investment advice. Opinions, estimates, forecasts, and statements of financial market trends that are based on current market conditions constitute our judgment and are subject to change without notice. Integrated Capital Management does not have any obligation to provide revised opinions in the event of changed circumstances. We believe the information provided here is reliable but should not be assumed to be accurate or complete. References to specific securities, asset classes and financial markets are for illustrative purposes only and do not constitute a solicitation, offer or recommendation to purchase or sell a security. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investment strategies and investments involve risk of loss and nothing within this report should be construed as a guarantee of any specific outcome or profit. Investors should make their own investment decisions based on their specific investment objectives and financial circumstances and are encouraged to seek professional advice before making any decisions. Index performance does not reflect the deduction of any fees and expenses, and if deducted, performance would be reduced. Indexes are unmanaged and investors are not able to invest directly into any index. The S&P 500 Index is a market index generally considered representative of the stock market as a whole. The index focuses on the large-cap segment of the U.S. equities market.

The TekRidge Center

50 Alberigi Dr. Suite 114

Jessup, PA 18434

Phone: (570)344-0100

Email: [email protected]

www.icm-invest.com