European integration has been a lengthy process, one that started only a few years after the end of World War II and continues to this day. For many casual observers, it is regarded as a unidirectional process that will slowly but surely end up with a supranational government, akin to the “United States of Europe” Winston Churchill once famously called for. However, a closer look at integration efforts during the last three decades yields a very different picture.

Further integration, at both the political and economic level, has suffered severe setbacks. Most of the times, voters themselves have stalled progress (Brexit being the most prominent example). The bedrock of economic integration, the euro, has been shaken more than once by crises in different countries. Calls for withdrawal are now louder than ever, even if they do not enjoy majority support yet. The common currency stands on shaky ground, and it is very likely that the euro area, as we know it now, will cease to exist within the next decade. This will, obviously, increase volatility in the region (in turn providing opportunities to savvy investors). The fact that the eurozone is not a fiscal union —like the U.S.— will constitute another hurdle for the common currency. We believe the dream of a European Union like the one the 50 American states have in place is pure utopia.

The beginning

The political and economic integration of Europe is an ongoing process that can be traced back to 1949, with the creation of the Council of Europe (still in place). The first major step towards what we now know as the EU was taken in 1957, when the Treaty of Rome laid the ground for the European Economic Community that started operating the next year. The founding members were (West) Germany, France, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg.

This organization would expand, until it became the European Union in 1993. It has continued growing since then, currently listing 28 member states.

Economic integration

The European Union is a political and economic union. Being a member requires certain requirements to be met in both the political and economic arenas. We will not discuss political integration —e.g., foreign policy, defense— in this paper. In terms of economic integration, the most salient feature of it is the single market, which guarantees the so-called “four freedoms:” free movement of goods, capital, services, and labor (i.e., citizens are allowed to settle and work anywhere within the EU). Only the 28 members of the EU fully participate in the single market.1 The European Union Customs Union includes all EU members, as well (plus a few other countries, most notably Turkey). This agreement precedes the EU, being a main feature of the European Economic Community. It is relevant because member states cannot negotiate international trade policy —including free-trade agreements— individually, handing over the responsibility to the European Commission to conduct trade policy on behalf of the bloc. Obviously, a customs union cannot work if goods pay different levies in different countries.

Much of the recent discussion about how to implement Brexit —the departure of the UK from the EU, the first member state to request it— revolves around trade policy. The UK would like to negotiate trade deals on its own, and, at the same time, remain in the single market. This has been completely ruled out by the EU. The UK is still trying to find a way to remain a part of the market in some way, centering its efforts in finding a formula that will preserve some form of customs union. So far, the EU has dismissed the UK government’s proposals. The EU negotiators have repeatedly stated that countries cannot pick amongst the “four freedoms.” It is reasonable to believe the UK would be willing to keep the first three, but definitely not the fourth, regarding the free movement of EU citizens.

The euro

A step further in terms of economic integration is the monetary union, that is, the adoption of a common currency.

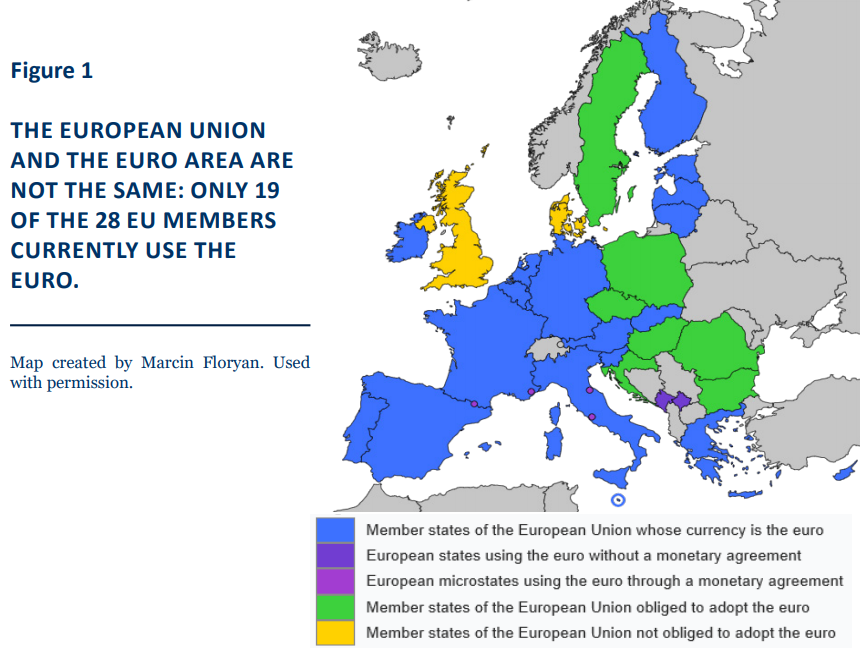

The euro was launched in 1999, and notes and coins were available in January of 2002. However, the common currency only applies to a subset of members —currently, 19 out of 28. Joining the euro is mandatory for members once they meet the requirements —which many of the economically weaker members currently do not (six of them, to be precise). Yet Denmark and the UK were given an opt-out, with the former rejecting the common currency in a 2000 referendum. Another country that could join is Sweden, which found a clever way to avoid adopting the euro: one of the requirements to be in the euro is being part of the European Exchange Rate Mechanism system, so the Swedes have decided not to join it, therefore bypassing the mandate to join the euro area. The remaining six countries are expected to adopt the euro at some point in the future, but that will take years. (These are Poland, Czech Republic, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, and Croatia.)

The benefits of the euro are a matter of contested debate. For weaker members, the common currency helped, at least, to stabilize and lower inflation (partly because it was a requirement to join the eurozone, and afterwards because those countries started using a stronger currency). Furthermore, the common currency should also help to lower debt levels: being in the eurozone carries limits to budget deficits (3% of GDP) and government debt (60% of GDP).

However, whether this is good or bad is itself subject to debate, given that it does not allow governments with high levels of debt to use fiscal policy as they might want to in times of economic contraction, making matters worse. This is the debate around austerity measures that has lingered for many years in countries like Greece, Spain, Italy, the UK, and others. Moreover, enforcement has not been strict. Italy’s government, for example, has a debt of approximately 130% of GDP.

Another benefit that weaker economies enjoyed was the reduced cost of borrowing money. Spain, for example, saw rates on its debt plunge to a third of what they were in the 1990s only a few years after the euro began circulating.

The risk premium over German bonds was reduced drastically. Other benefits include reduced transaction costs and risks (e.g., exchange-rate costs and risks), and more transparency, all of which have been a boon to trade. Capitals started flowing to the relatively poorer countries once the euro became the common currency. Spain and Greece are two states that benefited immensely from this. However, some economists have argued this helped to create bubbles, like the real-estate bubble that brought Spain’s economy to the brink of collapse (they had to bail out banks). The case of Greece is well known, with a recession so deep that it turned into a depression. The economy has not, to this day, fully recovered. GDP per capita is still far below 2008 levels.

Another minus of a common currency is that each country loses monetary-policy independence. That might translate into discipline, but at the same time prevents different monetary approaches across countries when they are needed.

After the sovereign-debt crisis that followed the financial crisis, countries like Greece would have probably benefited enormously from allowing their currencies to depreciate substantially. This would have made those economies more competitive (increasing exports) and flexible in the new scenario, without the swell in unemployment levels and the contraction in economic output that they experienced. In the Greek case, things were so bad that many investors were worried the country would be forced out of the euro area. The concern now is that they may never be able to repay their debts. More generally, the terms of trade become less flexible with a common currency. If each country had its own free-floating currency, the German mark would have appreciated in the post-crisis years. The euro has prevented this, and this is usually cited as one reason for Germany’s big current-account surpluses. Actually, Germany has had the highest surplus in the last two years ($287 billion, almost 8% of GDP, in 2017).

Additionally, these countries could have used more reflationary policies than those followed by the European Central Bank (ECB). Only in 2015 did the bank adopt an aggressive quantitative-easing program, coupled with already existing zero rates, to help embattled countries recover. All of these disadvantages have led Nobel-laureate economist Paul Krugman to label the euro a “disastrous decision.”

How strong is the Union?

Outside of Europe, the integration process was seen for a long time as unstoppable. With time, more countries would be added to the EU and the euro area, and more issues would be dealt with at a supranational level. Just as southern Europe had joined in the past, so would central and eastern Europe at some point, including many former Soviet republics. Even Turkey was mentioned as a potential future member, not least because of the latter’s own interest.

However, this level of progress has not materialized.

The Brexit vote sounded the alarm in 2016 for many U.S. investors. They started to wonder whether the union itself was going to hold. The annexation of Crimea in 2014 had presented an earlier warning, but markets seemed less concerned when that event unfolded. However, international observers have been asking the same question long before the 2016 vote in the U.K. People in Europe, when given the chance to vote, have rejected different forms of further integration since, at least, the 1990s. Support for European institutions has been the minority’s position in various referenda. Amongst them we can cite:

• Switzerland rejected becoming a member of the European Economic Area (EEA) in 1992;

• Denmark and Sweden voted against joining the euro in 2000 and 2003, respectively;

• French and Dutch voters said no to the European Constitution project in 2005, effectively killing it.

• Norway voted against joining the European Communities (EU precursor) in 1973 and the EU proper in 1995.