The most terrifying words in the English language are: I’m from the government and I’m here to help.

– Ronald Reagan

Top of mind for about every market prognosticator and most investors, for that matter, is the Fed and its ongoing battle with inflation. This is meaningful, not only for Wall Street, but for Main Street, at the intersection of the cost of mortgages and car loans, as well as the price of goods and services. Rates, as you are aware, are important not only for those making big ticket purchases, but also for the Fed to drive the final stake through the heart of inflation, something welcome by most. The comedy lies in our collective obsession with identifying the precise inflection point. In fact, it’s become a bit of a favorite pastime. We fall victim to it as well. Believe me, I realize the glass house in which I live and am not casting stones. Now admittedly, predicting this juncture is a difficult undertaking as there are hundreds if not thousands of variables that can derail even the most thoughtful prediction over short periods. As I mentioned in last quarter’s Market Insights, a convenient truth is that most of our clients are long-term investors, which aligns nicely with the fact that what we need to predict accurately occurs over longer term horizons. This is typically our focus.

Lately though, it’s hard to manage investments without being drawn into short-term commentary. It seems almost required. So, you’ve got me. I’m going to do it again, but not without making a perhaps not so obvious point. Does it really matter in the larger scope of things if the Fed cuts rates today, this summer or, for that matter, next year? The answer is a resounding no unless your time horizon ends at that interval.

Fed Watching

Ok, now that I’ve gotten my usual disclaimer about the folly of short-term predictions off my chest, I suppose we can talk about what has transpired since mid-December. I pick this date, not at random, but in essence marking the point when Fed Chair, Jerome Powell, indicated a shift in thinking and spoke of the possibility that the Fed Funds rate would be lower by the same time in 2024. This “pivot” cascaded through financial markets, sending rates across the yield curve lower and causing both stocks and bonds to rally substantially. As markets celebrated the possibility of a soft landing, lower rates, narrower credit spreads, and higher stock prices along with a more optimistic consumer loosened financial conditions. Is this necessarily a bad thing? After all, the goal isn’t to decimate the economy, it’s to vanquish inflation. The answer is, in this scenario, I think it is a bad thing. In last quarter’s Market Insights, I wrote the following:

As we all quietly hope for a soft landing or even a no landing scenario, I would offer a likely controversial take on this. Maybe we shouldn’t. In our current situation, inflation is likely subdued as the economy decelerates. Unemployment is ticking up just a bit and markets are grinding higher. The economy is growing, albeit at a slow pace. That’s a soft landing. But what happens when we shift up a gear into higher growth mode in a year or so? People spend more, companies need more labor, workers become scarce again which puts pressure on wages and on the availability of goods. That’s inflationary. There needs to be some slack in all markets (labor markets, equity markets, productive capacity, etc.) to account for the recovery and ensuing surge in demand. We may need to reach 5-6% unemployment to allow for the capacity to add jobs during any future expansion. Otherwise, the result is inflation. Similarly, equities need to correct to a level where the valuation is reasonable so that the ensuing recovery doesn’t take valuations to internet bubble levels of 40x P/Es or beyond. That’s the primary problem with a soft or no landing scenario. There is no room to recover without creating inflationary pressures and potentially having to restart the rate hike cycle, albeit from a higher beginning point.

The problem, I suspect, is what I identified last quarter. That is, absent some sort of weakening in labor markets, financial markets, or the broader economy, a reacceleration of inflation is a likely outcome. While I don’t enjoy or benefit from a recession, I think we need one to provide the spare capacity that I spoke of. That “slack” is the space to allow for the initial exuberance that comes with hope. Today, we lack the extra capacity. That recent exuberance has likely done the only thing it could have, reignite inflation.

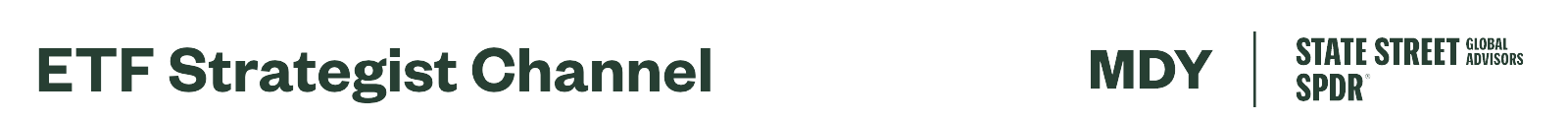

Now, allow me to put this in the proper context. At the moment, accelerating inflation isn’t terribly concerning in and of itself. It is limited to a few data points that tend to exhibit a high degree of seasonality. What’s more, when you drill down on where inflation is coming from, we can see that our current inflationary uptick is primarily the result of shelter and transportation services. Shelter, we know about. In fact, I addressed it last quarter. Housing is a bit of a distorted market due to not only underproduction post housing bubble, but also due to the current limited number of willing sellers as higher interest rates have removed many with low mortgages from the pool. This is a bit of an issue. What about the second item, transportation services? There are a number of components included in this category, but the primary source of inflation seems to rest with motor vehicle insurance and airline tickets. Not to dismiss it, but are airline tickets and car insurance top of mind for the Fed in their list of concerns? The million-dollar question is then, should the Fed again dismiss this source of inflationary pressure as “transitory?”

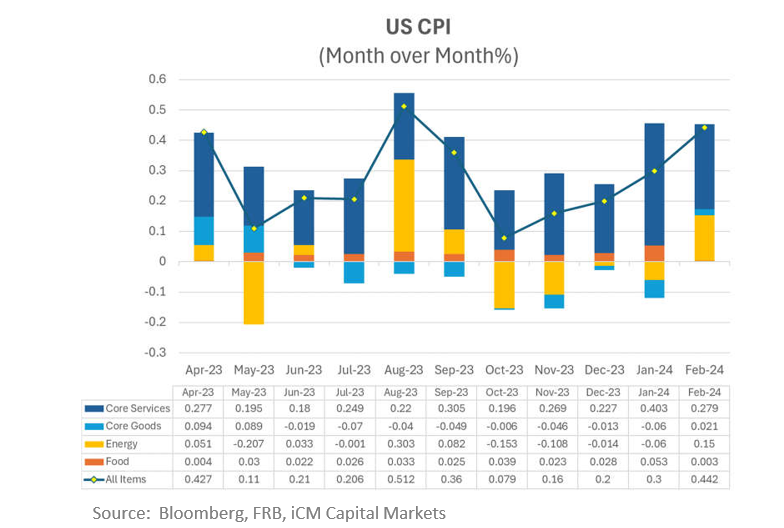

What is modestly concerning is the loosening of financial conditions and their potential impact on the trend. As financial conditions loosen, economic activity tends to accelerate. This can be seen in the chart below. Here we show the Bloomberg Financial Conditions index compared to US real GDP. As we can see, financial conditions tend to lead economic activity by about 90 days. While financial conditions tend to impact economic activity, they also tend to correlate to inflation, especially in those environments lacking the marginal capacity to produce or hire.

Now, there are several takeaways here. Loosening financial conditions can and did happen quickly. However, they can reverse just as quickly, delivering the weakness that will justify cuts later in the year, making the now higher-for-longer crowd look foolish. Absent that weakness, if the Fed continues with cuts, I believe we are witnessing a policy error. To durably vanquish inflation, there must be capacity to absorb the acceleration that occurs as the Fed further relaxes financial conditions. This occurs in things like new jobs and higher wages, stock and bond market rallies, and higher demand for goods and services, due to not only more jobs and higher wages, but also greater disposable income due to the lower cost of credit. If markets are at sky high valuations, maximum productive capacity, and full employment at the time of a pivot in interest rate policy, inflation is a likely outcome. We are just getting a taste of that now.

Election Year Dynamics

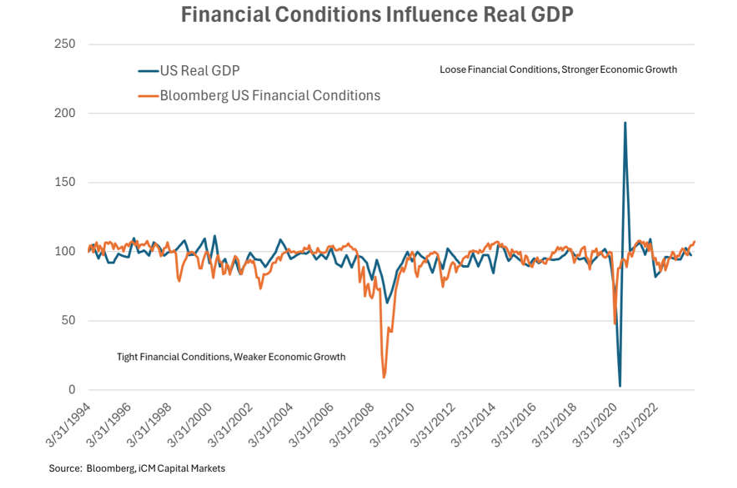

If conflicting data and anticipatory moves by financial markets and consumers are not complicated enough, the election year adds another dimension to the puzzle. Historically, the central bank has attempted to maintain a level of independence from political affairs. While noble, it is somewhat of a requirement given the psychological nature involved with their dual mandate… full employment and low inflation. As we witnessed recently, words can move markets and markets can move economic variables, in this case inflation. Credibility is a requirement if you are to maintain that power. People need to believe that what they say is motivated by objective analysis and not impacted by other priorities. Historically, monetary policy during election years has been a bit of a mixed bag. What it has not been, is uneventful. The Fed has typically been unencumbered by the presence of the election year, willing to implement its policy, whatever that may be. In fact, since 1980, there have been five hiking cycles during election years, totaling 837 bps of rate hikes and with half of that occurring in 1980. Likewise, rate cuts during election years have also occurred with frequency, also five times totaling 800bps of cuts. Leaving a grand total of a +37 bps bias for hiking during election years, essentially zero.

While the Fed does not mind being active during election years, in most instances, barring a crisis, they have been rather reserved during the election season of September – November. There have been five instances of policy action during election season since 1982, when the Fed began to directly target the Fed Funds rate: 1984, 1988, 1992, 2004, and 2008. In three of those years, the change was small, +/- 37.5bps or less. In the other two, the Fed was dealing with some crisis; inflation beginning to reemerge in early 1984 and the Financial Crisis in The only non-crisis election year in the past thirty where there was a policy change was 2004. That said, of the 125 bps of hikes that occurred that year, only 25 bps occurred during election season. While we can’t rule out policy action during the prime election months, the data seems to support the notion that the Fed would prefer not to act immediately prior to an election. In our view, this environment does not provide sufficient cover for the Fed to act aggressively during election season. Therefore, I suspect that any meaningful cuts will need to occur prior to September if their preference to maintain their independence holds.

For more news, information, and strategy, visit the ETF Strategist Channel.

Market Insights is intended solely to report on various investment views held by Integrated Capital Management, an institutional research and asset management firm, is distributed for informational and educational purposes only and is not intended to constitute legal, tax, accounting or investment advice. Opinions, estimates, forecasts, and statements of financial market trends that are based on current market conditions constitute our judgment and are subject to change without notice. Integrated Capital Management does not have any obligation to provide revised opinions in the event of changed circumstances. We believe the information provided here is reliable but should not be assumed to be accurate or complete. References to specific securities, asset classes and financial markets are for illustrative purposes only and do not constitute a solicitation, offer or recommendation to purchase or sell a security. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investment strategies and investments involve risk of loss and nothing within this report should be construed as a guarantee of any specific outcome or profit. Investors should make their own investment decisions based on their specific investment objectives and financial circumstances and are encouraged to seek professional advice before making any decisions. Index performance does not reflect the deduction of any fees and expenses, and if deducted, performance would be reduced. Indexes are unmanaged and investors are not able to invest directly into any

index. (MMXXIV)