Bull vs. Bear is a weekly feature where the VettaFi writers’ room takes opposite sides for a debate on controversial stocks, strategies, or market ideas — with plenty of discussion of ETF ideas to play either angle. For this edition of Bull vs. Bear, Karrie Gordon and Nick Peters-Golden debate the investment case for having exposure to China as part of an EM debt strategy.

Karrie Gordon: Increasing geopolitical tensions between China and the U.S. have left a lot of advisors asking, “Do I, or don’t I?” when it comes to including China in emerging market strategies. Due to the current global economic forecast, I’m bullish about emerging market debt ETFs that include and even focus on China, given the opportunities Chinese debt presents right now for advisors and investors.

China has massive debt, there’s no denying it, but it’s also a country that is looking to have GDP growth anywhere between 4%–6% this year when many countries are slowing substantially. While JPMorgan estimates that China’s debt to GDP will rise another 10% this year, Chinese companies benefiting from increased domestic consumption this year are likely to be less at risk for default as their cash flows recover from the challenges wrought by China’s zero-COVID policy, which was rolled back at the end of last year.

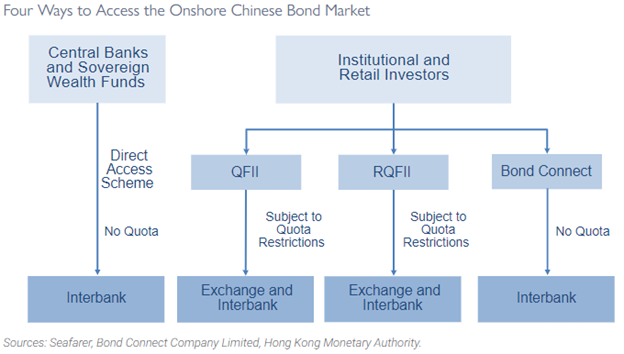

The majority of corporate debt in China comes from companies and entities that have at least some connection to the state. Still, the creation of a secondary bond market and expansion of access for international investors in 2017 has meant that debt has been diversified away from just bank balance sheets and across holders both domestically and internationally, creating better bond liquidity.

Image source: Seafarer

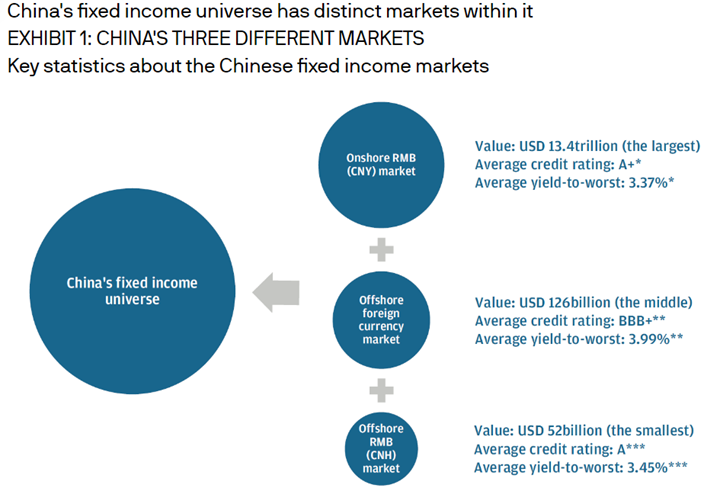

The structure of China’s bond markets also means unique diversification opportunities for investors between onshore (mainland) and offshore (U.S. dollar-denominated) debt exposure to China, with a low correlation between the two markets, creating alpha opportunity, according to BlackRock. Given that the strength of the U.S. dollar is likely to peak this year, investing in bonds through local currencies like China’s renminbi (RMB) allows investors a two-fold benefit: Diversifying away from the dollar can benefit a broad portfolio when the global economy is changing while also capturing potential local currency appreciation that can boost total returns.

Nick Peters-Golden: Let’s talk about Chinese corporate debt. It’s a bit too risky for me and for JPMorgan, which just proposed a new Asia credit index with weights toward China slashed due to political issues and a “dimming appetite” for bonds. Not only are corporates already in a lot of debt, but the system is so convoluted that corporate bonds are at risk of contagion.

China’s debt to GDP ratio hit a record high of three times GDP to close 2022. That’s much higher than advanced economies like the Euro area or the U.S., or even in the emerging markets category outside of China. Emerging markets debt has been an exciting place overall for investors, but China and Russia have been a drag, consistently pulling the default rate for emerging market corporate debt higher for the whole category.

China and Russia bring the default rate to 11% based on the JPMorgan corporate CEMBI, according to research at McKay Shields. Without the two, that number drops to 1%. Compare that to India, which is arguably behind China in the progress of its economy but has just a 4% average default rate for companies over the past decade.

In fact, halfway through last year, Chinese firms had missed payments on $26.2 billion worth of offshore bonds. A broader credit correction is underway just as $292 billion worth of debt for China’s debt-ridden property sector, made famous by the ongoing debacle for real estate development megafirm Evergrande, is coming due this year.

Those payments after a record wave of defaults loom large over corporate debt offerings, especially as the real estate sector has worrisome potential to impact the broader economy. But that relationship goes both ways, too — corporates need China to get back on track with growth because, according to the IMF, “lower potential growth risks worsening debt dynamics in the economy, as deleveraging through high growth becomes less likely, and creating challenging policy tradeoffs.”

Gordon: Defaults have been high, primarily driven by the property sector, it’s true, but supportive measures by national and local government agencies are bringing those numbers back in line for 2023. According to Bloomberg, analysts expect high yield property company defaults to drop by one-third this year, while the government has committed to a fiscal deficit of 3% of its economy in 2023 at the 14th National People’s Congress happening currently.

Peters-Golden: That all brings us to an important, additional point — the Chinese fixed income market is really complicated and twisted, thanks to its market socialist approach and command economy skeleton that undergirds it all. There are both onshore, Chinese renminbi-denominated fixed income securities and offshore fixed income securities denominated in foreign currencies.

The onshore securities can come from government and “government-related” entities, ranging from government banks like the Export-Import Bank of China to corporations themselves. The KraneShares Bloomberg China Bond Inclusion Index ETF (KBND) weights its Chinese debt securities half from government bonds from the central bank and other government banks and half from corporations and “other government-related entities” — leading to a messy web of bonds flying around the interbank system.

Take a look at this graphic from JPMorgan Asset Management for more color:

Source: JPMorgan’s market bulletins

In summary, there are a lot of big risks in the complicated world of Chinese corporate bonds, not only in the form of default rates but in onerous restructuring agreements that can cut into the rates found in corporate debt. The headline issues in the real estate sector with heavy debt aren’t exclusive to property, as there are increasing warnings signs for wider industries like construction, engineering, consumer discretionary, and consumer staples.

Gordon: The government has been engaged in a campaign to deleverage its nonfinancial debt and “shadow credit” since 2019, an agenda that got put partly on hold with the onset of the pandemic in 2020 and the pivot to working to support the beleaguered property sector. The corporate default rate seen since 2020 isn’t so much a signal of an impending debt crisis but arguably more a matter of China working to combat its bloated credit and create a more sustainable credit system. According to the World Bank, the corporate sector’s debt to GDP (excluding local government financing vehicles, or LGFVs) was approximately 117%, as of Q3 2022.

I can’t talk about China’s debt without discussing the differences in how China’s market and participants are structured. China has a socialist market economy and has been evolving from goods to a services-oriented economy, a transition that takes enormous government investment, as we have seen in China over the last two decades. Many of China’s corporations are state-owned enterprises (SOEs) that are either wholly or partially owned by the government and work to stabilize the economy and drive infrastructure growth and the economic evolution in China.

Because China is a socialist market economy, government policies and rhetoric indicate how the economy is being shaped and driven. A noteworthy change in rhetoric has happened in recent months as Beijing has become more business-oriented, aimed at supporting the recovery of its private industry struggling to recover from COVID-19 lockdown impacts, and is wholly dedicated to helping support the economy.

Peters-Golden: Becoming more business-oriented is one thing, but as the U.S.-China trade war deepens, it’s important to note too that not all businesses are supported by the government in Beijing — plus, in an already debt-laden environment, more government intervention could distort matters even more.

Gordon: True, but the rhetoric really matters, and thus far, it has been strongly in favor of realistic growth this year headed into the National People’s Congress. From President Xi down, Chinese officials are committing to boosting economic growth and letting slack into the economy for corporate growth, though the stimulus is likely to be more targeted going forward as the government also works to curtail extraneous debt. The People’s Bank of China recently announced that it will favor private companies as it seeks to support growth this year and improve real estate companies’ balance sheets as the industry transitions; such an accommodative policy approach for the private sector could reduce default risk.

Liu Kun, China’s Finance Minister, has also indicated that the government will be in support mode as it seeks to boost recovery this year through subsidies, stimulus spending, and tax cuts. While it remains to be seen what actual policy will come out of the 14th National Party Congress happening now, it’s strong rhetoric in favor of underlying support for the private sector and broad economy this year, and rhetoric carries great weight in China.

Peters-Golden: When talking about China, we’d be remiss if we failed to discuss the political pitfalls related to the country’s ability to manage financial risks. Now, I’m not one of those people who really believe that China is uninvestible overall — but President Xi Jinping’s consolidation of power over the country’s central bank, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), is a real issue for its response to all of this corporate debt risk.

Xi has installed a number of his key associates to lead the central bank, limiting the extent to which investors and China watchers can rely on the bank as a guide to interest rate policy. Back in 2021, China’s Prime Minister Li Keqiang told the IMF that the reserve requirement ratio would be cut to boost the economy, with the bank announcing the cut just three days later.

Yes, corporations in China may benefit from the political machinations that produce a long-lasting regime of low rates, but central banks are more than just a lever that reads “inflation up” or “inflation down.” The central bank has a huge remit in financial regulation, and political motivations to keep corporates alive in a financial crisis could easily lead to mismanagement of their debt or a huge restructuring of their bond arrangements for global creditors — including ETF investors left holding the bag.

The PBOC move is just the latest in a series of events that indicates that there may be less transparency in China’s economy moving forward, including pressure from the Ministry of Finance on state-owned firms to shun some of the biggest international accounting firms.

Gordon: All fair points, and there is absolutely a consolidation of power happening under President Xi and a level of risk that inevitably comes with that, but it’s worth coming back to the point that this is a government that is both aware of its debt issues and working to reform its credit system while reducing borrowing. Also worth mentioning is that China’s Premier Li Keqiang has officially set its growth target at 5% this year, a reasonable goalpost that should require less government borrowing to support the economy overall.

Peters-Golden: The European Central Bank’s economic bulletin has highlighted a related issue, that risk remains underpriced for corporate debt so long as China’s “shadow banking” sector creates an implicit expectation that the government will help guarantee returns. It’s a classic case of moral hazard that implicates the LGFVs, a frequent participant in the shadow banking sector.

The reason to be concerned about the LGFV debt, as a quasi-government organization, is that while not all corporate debt in China is securitized, much of the corporate bond default rate in the past has been the result of weak credit availability in provinces, according to the Rhodium Group, where the LGFVs that back up corporations are themselves facing defaults on their own bonds and thus limiting their ability to backstop troubled corporates needing new credit lines.

That presents a contagion risk if China’s government is expected to step in, and if it’s politically compromised, that invites even more complication. Many LGFVs are under pressure and can no longer issue bonds in China’s domestic market or, crucially, refinance maturing debt, according to the Economist. In short, it’s a twisty setup with precious little transparency and a lot of delicately balanced arrangements that are straining.

Gordon: Right now, there are some really noteworthy yields happening in high yield bonds in Asia and China compared to the U.S. that most U.S. investors are likely missing out on: As of the end of 2022, Asian high yield bonds had yields of 12.9% while U.S. ones had 8.8%, according to KraneShares, and Asia had a lower high yield default rate than the U.S. in 2019 and 2020. The FTSE Chinese USD Broad Bond High-Yield Index, as of the end of January, had corporate high yield bonds with an overall yield-to-maturity of 15.65%.

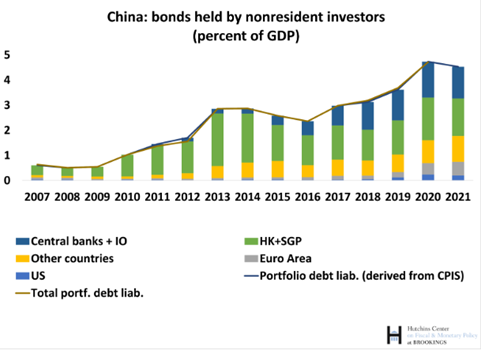

U.S. investors historically have an underallocation to Chinese bonds, according to a recent academic analysis from IMF, the Brookings Institute, and the European Central Bank.

Image source: Brookings

There are various options for advisors looking to capture the yield opportunities happening right now in emerging market bonds with a focus on China and diversification opportunities in both onshore bonds and offshore U.S. dollar-denominated exposures. For offshore exposure, the actively managed KraneShares Asia Pacific High Income Bond ETF (KHYB) has a 30-day SEC yield of 9.91% as March 2, 2023, is USD-denominated, and is benchmarked to the JPMorgan Asia Credit Index Non-Investment Grade Corporate Index with exposure to high yield debt from companies in Asia and a management fee of 0.68%.

Peters-Golden: Important to note, too, the cost of owning those ETFs on top of the uncertainty in the market there — 68 basis points in a world of passively managed low-fee funds tracking foreign debt indexes is a gut check moment, to be sure.

Gordon: Those advisors and investors looking for higher-grade offshore bond exposures should consider the iShares J.P. Morgan EM Corporate Bond ETF (CEMB), which has a 30-day SEC yield of 6.40% as of March 1, 2023, and offers passive exposure to USD-denominated bonds issued by EM corporations. The majority of CEMB’s exposure is to bonds rated between AA–B, with China the heaviest-weighted country at 8.07% and management fees of 0.50%.

For exposure to EM government bonds through local onshore currencies, the passively managed VanEck J.P. Morgan EM Local Currency Bond ETF (EMLC) has a 30-day SEC yield of 6.94% as of March 3, 2023, and China is the heaviest weighting in the fund at 10.58% as of February 28, 2023, with management fees of 0.30%. For onshore allocation with a focus on China, specifically through RMB-denominated bonds, the KraneShares Bloomberg China Bond Inclusion Index ETF (KBND) is worth consideration and provides exposure to investment-grade corporate bonds alongside Chinese Treasuries with a 30-day SEC yield of 1.70% as of March 3, 2023, and has fees of 0.48% right now with fee waivers that expire August 1, 2023.

Peters-Golden: To me, the main point here is that risk should drive investors to look elsewhere for yields — but they don’t have to look too far away. Emerging markets are still an intriguing place for foreign fixed income, just as long as China exposure is limited — on top of all these risks, the S&P China Corporate Bond Index, is only yielding 3.15%. That’s pretty weak for all that risk when you can get a 5.52% yield from the S&P 500/MarketAxess Investment Grade Corporate Bond Index.

Advisors can access the latter index in the ProShares S&P 500 Bond ETF (SPXB), which charges just 15 basis points for exposure to those investment-grade corporate bonds. Investors can also go for the WisdomTree U.S. Corporate Bond Fund (WFIG), which charges 18 basis points and tracks the WisdomTree Corporate Bond Index, which has also seen better yields than corporate bonds in China, with 5.63% yields to maturity.

Still looking abroad? Why not try the actively managed WisdomTree Emerging Markets Local Debt Fund (ELD)? It has higher weights for bonds from places like Brazil and South Africa than it does for China, returning 290 basis points YTD, about 215 basis points more than either its ETF Database category average or its FactSet segment average, adding $4 million in net inflows over the last month. ELD charges 55 basis points for its approach.

Basically, there’s an opportunity cost when it comes to investing in Chinese corporate debt. There are too many other options and ways to diversify to ignore in favor of a politically compromised and yield-limited investment area on a yield basis and on a performance basis.

Gordon: Let me reiterate by saying I’m not rose-colored glasses about risk when it comes to investing in foreign debt, particularly in China. It’s a complex morass that requires careful and educated awareness of what is being invested in, and for some clients, it may be outside of their risk tolerance. What I am saying is that it’s not just a black and white picture, and for those that are willing to navigate some of the gray areas, there’s real diversification and yield opportunity to include China in EM debt strategies this year.

Nick, it’s been really great doing this, and I’ve enjoyed the chance to try and make what’s usually such an opaque area of investing maybe a little less so. Now speaking of black and white, I’ve got a strong hankering for green tea, so I’ll hang up my bull horns until next time.

Peters-Golden: Likewise! I always learn a lot chatting about all things China, and I’ll undoubtedly watch whatever the government there does with monetary policy. I wish my own household had a vigorous and independent central bank, sometimes, myself!

For more news, information, and analysis, visit the China Insights Channel.