Just when we thought that the inflation narrative might be easing somewhat, the latest CPI print came in at 9.1%, reigniting its specter over, well, just about everything.

As a macroeconomic neophyte, I tend to sponge what I can from every side of the inflation conversation without judgment and then move on. But one idea recently rankled me.

“We need five years of unemployment above 5% to contain inflation…,” said former US Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers in a speech in London, according to Bloomberg. “In other words, we need two years of 7.5% unemployment, or five years of 6% unemployment, or one year of 10% unemployment.”

Unemployment currently sits at 3.6%.

To my uninitiated thinking, Summers’s argument seems dire. I concede that it makes sense that if enough people can’t afford a place to live or food to eat, the price of living and eating might come down–but is that really worth it? In 2022, is this truly the only economic tool available?

CPI and Inflation

To understand if wide-ranging unemployment is the only tool in our toolkit, we need to go back to basics to better grok what the problem is.

Inflation is a collapse in the purchasing power of money. That’s not the same thing as CPI, which tracks the price changes of a basket of consumer goods. Though CPI is a measurement that reflects inflation, what it actually represents is a very specific thing.

Several factors cause inflation. Changes in demand or production costs can impact how much a good or service costs. If materials and labor are more expensive, then, to turn a profit, a good or service will need to be more expensive. If more people have resources available (because, say, they have secure jobs and are making money), then that too can increase demand for goods and services, driving up prices. Similarly, if supply is crippled, then goods will be more scarce, thus increasing their demand and thus their cost, which in turn makes a single unit of money less powerful.

On a recent episode of Citations Needed, Josh Mason, Associate Professor of Economics at John Jay College at CUNY said, “When you say inflation, you imply that there’s one thing going on, one economic process, one source, one set of causes and one solution. And the truth is, you know, that’s really not true.”

This means inflation isn’t just one thing with one cause. The price of housing is innately driven by different factors than the price of oil, which depends on other factors than the price of food or healthcare. Not all of these things are even tethered to labor at all. For example, housing and energy prices are more about scarcity than how much an American worker is making.

Phillips Throws Us a Curve

Summers is working with a simple theory: Lower unemployment rates increase a worker’s ability to demand a better salary. If workers get better wages and more people are working, then more people have money. If more money chases the same goods, then prices go up.

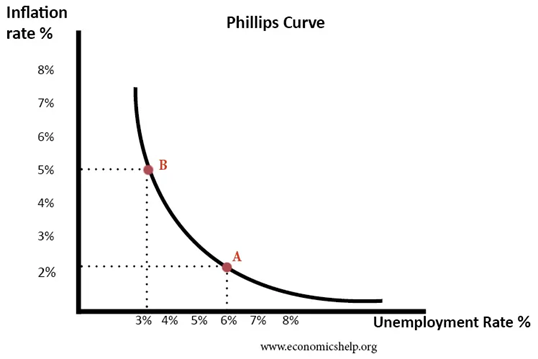

This theory is often represented in the Phillips curve, originally put forth by economist A. W. Phillips. which demonstrates the rate of unemployment vs. the rate of inflation:

This theory had broad acceptance for some time following World War II, until stagflation put the model in doubt. The ‘70s saw high unemployment mixed with high inflation. Meanwhile, later periods (such as 2010-2020) would be marked by low unemployment and low inflation.

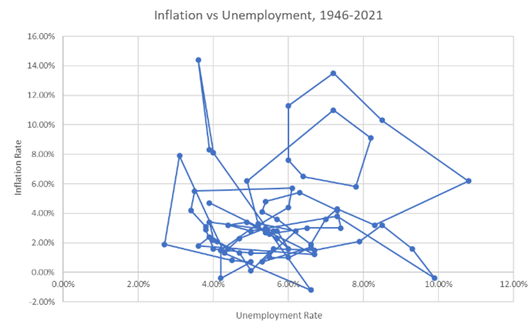

A further illustration of how shaky the Phillips curve model comes from Twitter user @Itmechr3, who saved me a heck of a lot of time by charting inflation on top of unemployment:

It seems pretty clear to me that, if low unemployment rates correlate with high inflation, this chart shouldn’t look like something my cat hacked up.

Is It All Labor?

The story Larry Summers and company prefer is that unemployment rates alone drive inflation. But it is abundantly clear that many factors go into inflation, so why simplify the narrative to focus on employment? Would full employment be a bad thing for society?

To some folks, it absolutely would be. Many workers stay in positions that underpay because they worry about their prospects if they leave. Particularly in the United States, where basic healthcare is tied to employment, workers often face enormously high stakes if they decide to leave a job. Under full employment, this would not be the case. Which, to my neophyte’s eye, seems like a good thing – even if it does cause some inflation. People should have options.

Economists such as Michał Kalecki believed that, aside from being economically sound, full employment was necessary for a society to thrive. His 1943 essay on full employment points out that one of the reasons Germany had turned toward fascism was because fascism offered full employment at a time when unemployment was rising. This full employment was, of course, the sinister revival of Germany’s dormant military machine. Still, Kalecki concluded that if they wanted to survive, capitalist countries would need to find their own path toward full employment, lest their citizens be tempted by fascism. Kalecki was skeptical of nations’ ability to do that, however, as unemployment was highly useful to business leaders.

In the essay, he writes:

“Every widening of state activity is looked upon by business with suspicion, but the creation of employment by government spending has a special aspect which makes the opposition particularly intense. Under a laissez-faire system the level of employment depends to a great extent on the so-called ‘state of confidence.’ If this deteriorates, private investment declines, which results in a fall of output and employment (both directly and through the secondary effect of the fall in incomes upon consumption and investment). This gives the capitalists a powerful indirect control over government policy: everything which may shake the state of confidence must be carefully avoided because it would cause an economic crisis.”

When Summers suggests the only path out of inflation is for 1 in 20 people (or more) to be condemned to poverty, I think about Kalecki’s warnings. Bombing the village to save it feels more like Nixonian/Kissinger foreign policy than it does a sound economic plan for America in 2022.

Decreasing demand, as Summers suggests, is one way to impede inflation. High unemployment, recessions, economic slowdowns, and fear will all destroy demand, to be sure. But there is another avenue forward: supply enhancement. Investments in infrastructure, re-shoring our societal structures, fixing broken supply chains, and making existence easier for humanity enhances supply and remove the need to destroy demand. It’s better for a larger number of people and shifts the cost of solving inflation away from the most vulnerable members of society, those living on the margins.

Labor’s Moment

Labor is having a moment right now for a myriad of reasons. Workers at Amazon and Starbucks are unionizing, there’s unrest over the lack of change to the minimum wage, and the COVID-19 stimulus packages put together by both the Trump and Biden administration sparked a national debate about unemployment benefits, one that is still very much alive today. Sen. Mitch McConnell recently said, “You’ve got a lot of people sitting on the sidelines because, frankly, they’re flush for the moment. What we’ve got to hope is once they run out of money, they’ll start concluding it’s better to work than not to work.”

Summers is saying we need more unemployment, and Mitch McConnell is saying that people are choosing not to work because they got $1800 from Trump when COVID started, then another $1400 from Biden about a year and change ago. Thinking about these things brought up two thoughts: The first one being “hey, wait, doesn’t Biden still owes us all $600 as per his initial campaign promise?” and the second being that both these threads tie into a general fear about rising wages causing hyperinflation.

Historically, we have only seen hyperinflation occur when states collapse, usually due to being on the losing end of a war. Germany’s loss in World War I led to hyperinflation. Yugoslavia shattered in the ’90s and saw hyperinflation. The US has certainly had its moments of strife but remains a powerful, solvent country overall.

Neither Summers nor McConnell, however, have acknowledged that over a million workers recently died. Of course, there are staff shortages right now. People aren’t holding out for higher salaries because they got $3200 during a pandemic; workers just have more leverage for a variety of reasons–the most morbid of which being that the labor pool is significantly smaller than it once was.

Mason also noted on Citations Needed, “You’re right to be skeptical about stories that too much power for labor, too many people can be too picky about jobs, and that’s the cause of inflation. I think you’re right to be critical of that. But it is actually the case that the balance sheets, the finances of most American families are much better than they were a couple of years ago. I don’t think we want to go so far that we dismiss the real success of the pandemic economic response in sheltering American families from what otherwise could have been an absolutely devastating economic disaster.”

Yet even understanding that American workers are more flush with cash and in possession of more economic leverage than they’ve had in a long time, Fed chair Jerome Powell recently conceded that rising American wages aren’t driving inflation. Powell and the Fed are raising rates rapidly in the hope of hitting a Goldilocks scenario where they manage to slow down inflation without necessarily knocking unemployment too high at the bottom of the economy.

Living in Inflation Nation

The case Mason makes is that a myriad of solutions needs to be presented, each catered to a specific problem. Many of these solutions are supply enhancers instead of demand destroyers. Notably, he points to widespread investing in bus services and mass public transportation to relieve the squeeze Americans are feeling at the pump and the car dealership. Other ideas put forward include public subsidies to make childcare more affordable, implementing rules that keep pharmacy prices down, capping rents, and bringing down the value of housing. Heck, even the successful COVID lockdown plan of stimulus is on the table – California plans to send people money to help them make up the gas gap.

As evidenced by the number of diverse causes, people, and institutions that all share the blame for inflation, it stands to reason that diverse, wide-ranging solutions could be helpful. Some of these ideas may not work, and some might face political headwinds. Some good ideas that genuinely make life easier and better for more people might also have inflationary effects. If we’re doing the right thing, though, I believe it’s a worthwhile trade-off. Because the goal of all of this [gestures broadly at society] is supposed to be shared safety and prosperity, right?

Personally, I’d rather not bomb the village, even to save it. Much like inflation isn’t just one big economic force, 5% unemployment isn’t just “some unemployment.” In a country of 260 million adults, that’s 13 million people with no way to afford to exist. Thirteen million human lives fed through the poverty grinder so the rest of us can feel a little more comfortable doesn’t seem like a good trade, especially not when we have other options on the table.

For more news, information, and strategy, visit VettaFi.com.