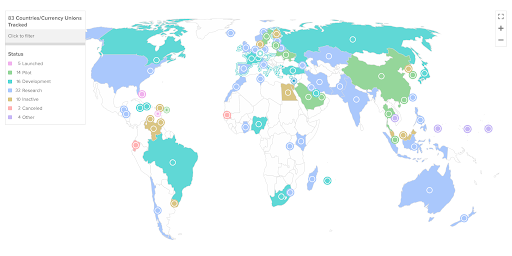

Central bank digital currencies, or CBDCs, have been making an increasing number of headlines this year — and for good reason. The number of countries said to be exploring CBDCs has doubled in the past year, according to a tracker released in July by The Atlantic Council, a D.C. based think tank:

Source: atlanticcouncil.org/cbdctracker, August 25th, 2021

“It’s an enormous increase,” said Ole Moehr, associate director of the GeoEconomics Center at the Atlantic Council. When the first version of the tracker was released last year, only 35 countries were exploring CBDC development. As of this July, there were 81.

CBDCs could solve one of the most persistent problems in banking: how to broaden financial inclusion for traditionally underbanked populations. However, they’re not without their own regulatory and structural hurdles.

Still, increasingly the question isn’t if the U.S. will develop its own digital dollar, but when.

What Is a CBDC?

A CBDC is digital money issued by a central bank; just as the U.S. Federal Reserve prints dollars and mints coins, it could also issue digital dollars and coins.

Whereas other digital currencies (aka, cryptocurrencies) are issued by private companies or mined as part of a decentralized network, CBDCs would be issued by the government, and exist as a digital version of an existing physical currency.

However, CBDCs would function technologically like other digital currencies, using the same distributed ledger technology. Essentially, a distributed ledger is a database spread across a network. Blockchain, the technology underpinning Bitcoin, Ethereum and most other major cryptocurrencies, is arguably the best-known example of a distributed ledger.

As of August 2021, five countries have fully launched CBDCs under two central bank regimes. The first was the Bahamian Sand Dollar, issued by the Central Bank of the Bahamas in October 2020, while in March, the Eastern Caribbean Central Bank launched Dcash for Antigua and Barbuda, Grenada, Saint Lucia, and St. Kitts and Nevis.

CBDCs Can Broaden Financial Inclusion

The Caribbean CBDCs were developed to broaden financial inclusion and access. For example, as the member nations are composed of multiple islands, in-person banking is not always easy or feasible.

The Bahamas Central Bank Governor John Rolle told Bloomberg in May that not only is physical banking in the country more costly due to island geography, but frequent hurricanes and national disasters can threaten financial access as well. Wireless payment systems using digital currencies can allow commerce to recover quickly in the aftermath of a disaster, even if individual bank branches and their cash reserves take longer to restore.

Even in larger economies, financial inclusion is a big part of CBDC discussion.

“A central bank digital currency could provide an onramp into financial services for traditionally underbanked populations,” said Chris Giancarlo, Senior Counsel to Willkie Farr and Gallagher. Giancarlo is also a former chairman of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission who co-founded the Digital Dollar Foundation, a non-profit which seeks to explore a U.S. CBDC.

According to a recent FDIC survey, over 5% of U.S. households are unbanked, meaning that some 7.1 million households do not use banks in any capacity.

Being unbanked can cause a multitude of problems. Unbanked individuals often must use prepaid credit cards to handle transactions that banked consumers would use a credit card for; these prepaid cards often come with high fees. They also do not allow users to build credit, and without a credit history, unbanked consumers cannot access loans. They may also run into issues accessing employment, insurance, and rental opportunities.

During COVID-19, the unbanked were put at an even greater disadvantage, as the IRS prioritized direct deposit stimulus payments to individuals with bank accounts over those who would require paper checks, meaning many already vulnerable households had to wait months for much-needed funds.

The Digital Dollar vs. Stablecoins

Despite their benefits, CBDCs would have likely remained a mostly theoretical exercise in the U.S. if it weren’t for the rise of stablecoins, or privately issued cryptocurrencies linked to stable assets, such as the U.S. dollar.

Regulators have expressed concerns that the lack of transparency into stablecoins’ cash backing could result in the U.S. losing some monetary control.

For example, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell has said that one of the strongest arguments in favor of developing a digital dollar is that the CBDC currency could compete with an emerging stablecoin market.

“The whole conversation around CBDCs was pushed to the front burner by the rapid rise of privately issued stablecoins,” said Sean Stein Smith, assistant professor of economics and business at Lehman college and a member of the advisory board for the Wall Street Blockchain Alliance, a non-profit trade association for financial professionals.

For the moment, the U.S. is markedly behind in CBDC development, compared to other developed economies. The Bank of Japan, Bank of England and the European Central Bank have all announced that they are actively researching CDBCs, while the Fed has not yet announced any official plans.

Fed Chair Jerome Powell is frequently quoted as saying, “it is far more important that the Fed get a digital dollar right than it is to move quickly.”

See also: While Support Grows For Fed-Issued “Digital Dollar,” Progress Is Slow

Moehr agrees. “Given that the United States has the global reserve currency” as well as “the deepest most liquid global financial market,” the U.S. has to get it right, he says.

But this does not necessarily mean that the U.S. has no role to play in the meantime, he adds. “At the Atlantic Council, we believe the US can still lead in the international arena in terms of shaping standards and regulation without necessarily having to pursue their own digital dollar at home.”

How Best to Regulate a Digital Dollar

Regulation is key in determining both the use and design of CBDCs, says Moehr. “As countries develop their CBDCs and make certain design decisions the trade-off between security and privacy will be a really key question for central banks.”

A CBDC would not only need to be secured against cyberattacks, but also sufficiently address concerns about the privacy of citizens’ financial data and autonomy. It must also balance those concerns against the central bank’s need to prevent money laundering and terrorist financing.

Most central banks worldwide seem to be exploring a “two-tiered” system for their digital currency. In a two-tiered system, central banks issue the coins while traditional banks and payment service providers manage the individual accounts, serving as facilitators and taking on the important customer-facing work vital to the standard anti-money laundering and anti-terrorist financing operations. Such a system helps preserve some of the protections embedded into the current banking structure.

Additionally, some central banks are considering limits on CDBC transactions and account balances. The European Central Bank, for example, has suggested that each person might be allowed only 3,000 digital euros, limiting the ability of the digital euro to disrupt the traditional euro-based economy.

Would CBDCs Really Kill Crypto?

Although CBDCs and stablecoins are often pitted against one another, many experts believe it is unlikely a CBDC would phase out other cryptos entirely. In fact, widespread CBDC use could be good for the broader cryptocurrency market.

“Having [a CBDC]come in helps the market figure out what the path forward for bitcoin is,” said Stein Smith. “Is it a currency? Is it a gold equivalent? Or is it its own new type of asset class?”

A digital U.S. dollar could help solidify Bitcoin as a store of value rather than a transactional currency, he said, adding that a CBDC would offer the same convenience and accessibility as any privately-issued digital currency.

According to Stein Smith, the argument that CBDCs and cryptocurrencies cannot coexist rests on the already disproven belief that the U.S. financial market can’t incorporate new asset types or products.

As Stein Smith says, “All you have to do is go back to 1990 or 1985 and see how many new ETFs, mutual funds, and other products have come into the marketplace, to see how incorrect that attitude is.”

For more news, information, and strategy, visit the Crypto Channel.