Much of our analysis is focused on what can go wrong; this is something that George Soros offered as his recipe for success. He would decide on a course of action then focus on all the factors that could prove him wrong. By adopting this methodology, he avoided one of the banes of investing: confirmation bias. Confirmation bias is the tendency to only focus on news and factors that support one’s position and ignore factors that weaken one’s case. Therefore, after we make a market call, we do look for things that could prove us wrong.

In our 2016 Outlook, the base case is for modest gains in equities, slow economic growth and continued low interest rates. We offered four caveats that would cause our forecast to be unduly bullish. However, we didn’t offer comments about what could make us too pessimistic. To some extent, this makes sense. Investors probably need to be more prepared for what could go wrong rather than what could go right. Weather forecasters seemingly overestimate snowfall or weather severity with the idea that not predicting a record snowfall is more of a problem than preparing the public for an epic storm that fails to materialize. Of course, there is always the potential for “crying wolf” too often, although permabears always seem to have an audience.

So, what could be the bullish surprise for next year? The most likely candidate is a stronger consumer.

This chart shows the three-year average of consumption’s contribution to GDP growth. Consumption fell precipitously in the last recession and its recovery has been steady; however, the current average contribution remains well below levels historically seen at this stage of a recovery. Still, the trend is clearly rising and, on a three-year trend basis, is adding 178 bps to GDP growth.

What could bolster consumption in 2016?

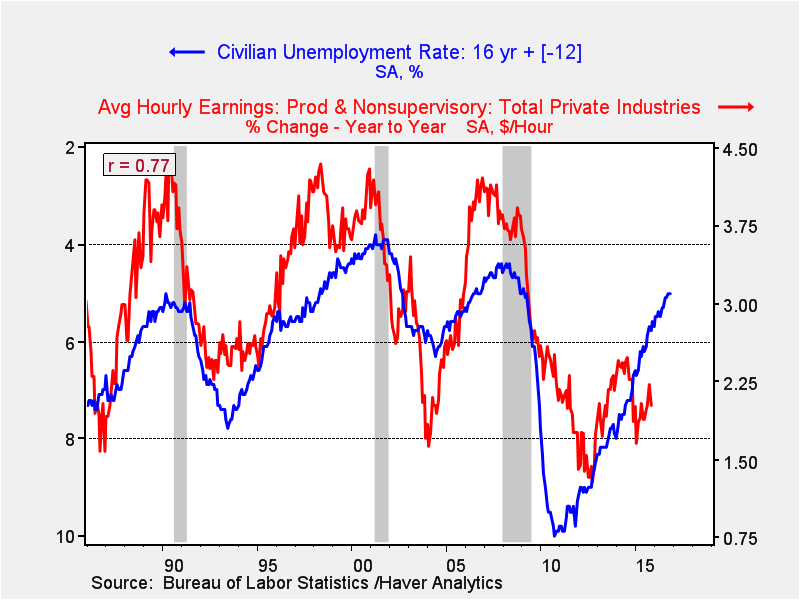

Wage growth: Usually when the unemployment rate is this low, wage growth improves.

This chart shows the yearly change in wages for non-supervisory workers along with the unemployment rate on an inverted scale. The unemployment rate tends to lead wage growth by about a year. In the past, an unemployment rate at this level has coincided with wage growth around 3.75% or higher. Although changes in the labor market may have changed this relationship, clearly the more hawkish members of the Federal Reserve fear that we will see a jump in consumption and higher wages that could lead to higher inflation.