Exchange-Traded Funds (ETFs) are often hailed as a major financial innovation. Seen by some as next-generation mutual funds, these securities are generally considered to be more tax efficient than their fund cousins, while providing investors with intraday liquidity as well.

The key to this process is arguably the creation and redemption mechanism. This allows ETF issuers to create new shares when demand outstrips supply, or redeem ETF shares when supply overtakes demand.

This system is generally between what is known as an Authorized Participant and the ETF issuer. When shares of an ETF are created, the Authorized Participant “AP” will deliver shares in-kind of the underlying constituents in exchange for units of the ETF. For redemptions, the opposite holds true; the AP would deliver the issuer the ETF in-kind for shares of the component securities.

While this may seem like a technical nuance, it is actually the heart of the ETF process. Due to the creation/redemption mechanism, APs can arbitrage away any difference between the components and the ETF’s price, thereby helping to keep the trading price of an ETF in line with the value of its underlying securities.

In practice

This is easy to visualize for a well-known benchmark such as the S&P 500. An AP following this index would simply buy up all the component securities and deliver this as a basket to an ETF issuer. Such a process isn’t too difficult because all of the S&P 500 stocks are extremely liquid and there isn’t an overwhelming number of securities to purchase in order to create the basket.

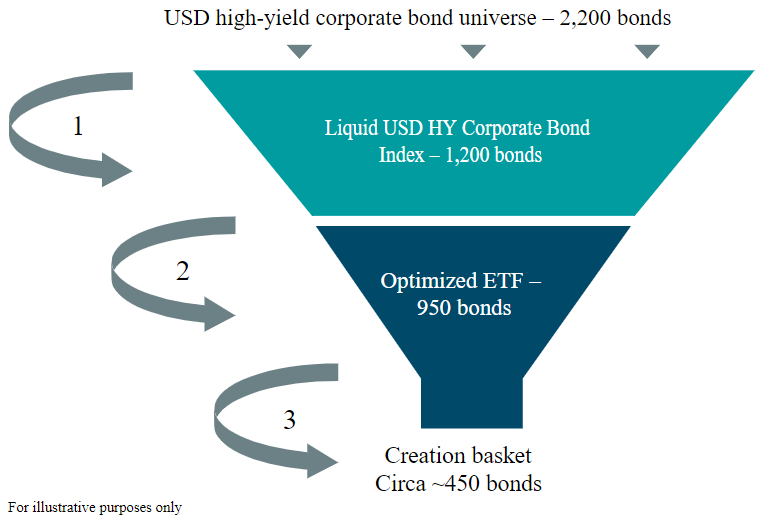

While that is pretty straightforward, what about for the world of fixed income? Bonds do not trade like stocks do, while the Bloomberg USD High-Yield Corporate Bond Index—a major benchmark of sub-investment grade-rated debt—has over 2,000 securities. And this doesn’t even begin to touch upon the issue of different maturity dates, again, something that is irrelevant for stocks. Clearly, the world of fixed income can be more complicated when it comes to building and maintaining an ETF. So how do fund managers solve these issues?

Replication vs. sampling

With a benchmark such as the S&P 500, a fund manager would use what is known as ‘full replication’. This means that the manager would buy each and every security that makes up a given benchmark. However, for a massive benchmark such as the high yield one described above—but also hard-to-trade equity markets and other illiquid investments—a ‘sampling’ process is used instead.

This means that the fund managers do not need to hold all of the securities in an index, but instead obtain a representative sample. Sometimes, this can be but a small fraction of the original index amount, though the goal is to deliver similar returns and risks as the original. For the high yield bond world, our process looks like this: