For all they lack in economic merit, tariffs and trade wars are certainly keeping us busy here at DWS. As a key provider of access to Chinese markets, recent events have seemingly led to more focus, attention, and questions on this region, than ever.

And, one that we have as often as any, is the question of valuation. How has the sharp decline of last year, and the equally sharp rebound for much of 2019, left the China A-share equity market looking? Here are three thoughts on just that.

Metrics

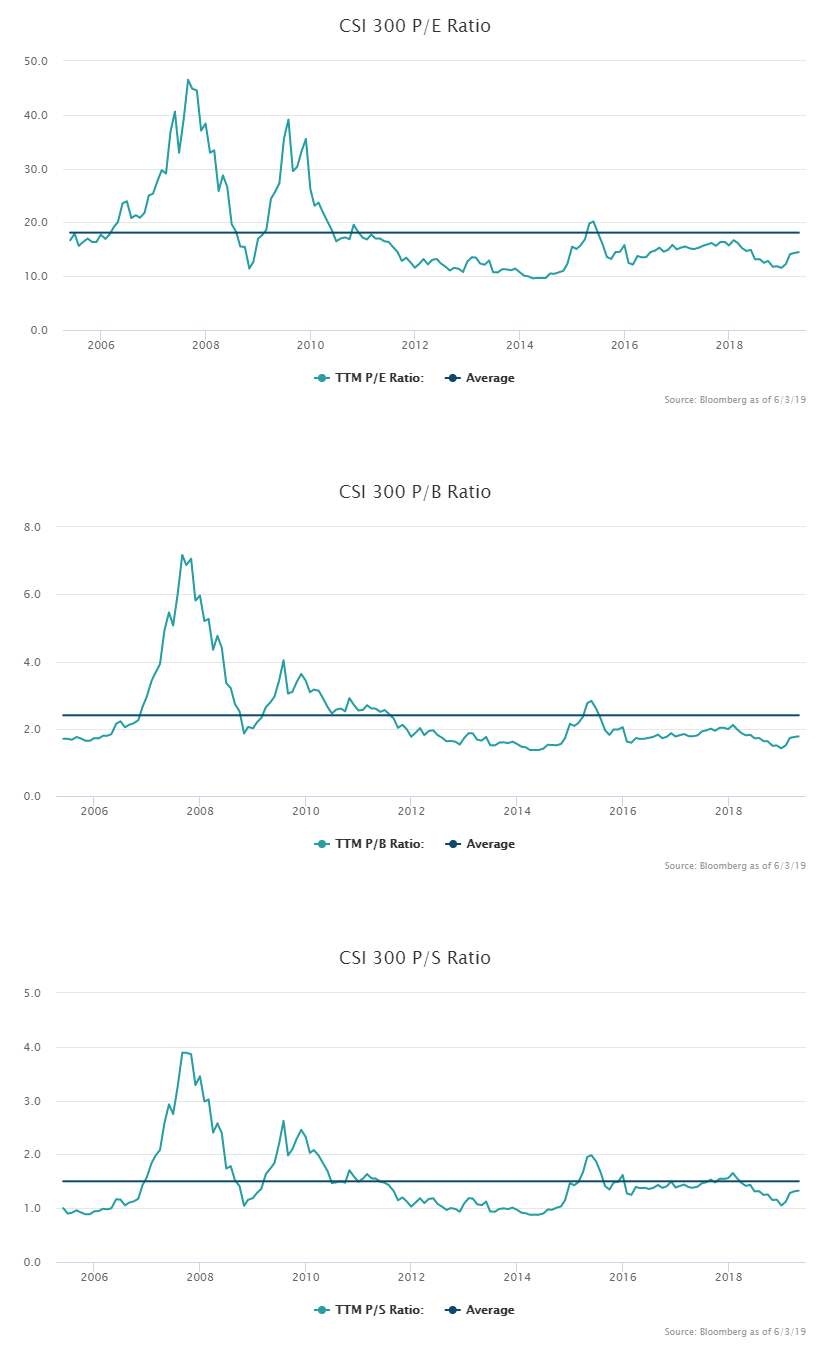

Since the debate around the relative merits of various valuation metrics (the valuation of valuation?) is an enormous topic, perhaps we can offer a blindingly simple solution – look at a few. For those worried about the continued relevance of Price-to-Book (P/B), or the cyclicality of Price-to-Earnings (P/E), it seems to us that running a couple of different metrics is a straightforward and pragmatic solution. The below charts show perhaps the “big-three” of valuation – price-to-earnings, price-to-book and price-to-sales (P/S). Perhaps reassuringly, the story doesn’t change too much regardless of which valuation measure we use, but that might not always be the case. There’s a reason why three judges sit ringside.

Figure One: Three Valuation Metrics for the China A-share market – Price to Earnings, to Book, and to Sales (5/2005 – 4/2019, source Bloomberg)

Myopia

Myopia may be too strong of a word, but in this final section, we wanted to highlight two additional points about valuation that we think are important – one obvious, and one more subtle.

The obvious one is that valuation to other markets must be placed in historical context to be meaningful. By which we mean that, if an investor were to witness an equity market currently trading at, let’s say, a 20% discount on a P/B basis versus the US, it would be myopic to believe that were cheap. And the reason of course is that equity markets can, and do, trade on different long-run valuations. For instance, if the Chinese equity were observed to have a long run historical P/B discount to the US of around 30% (which it turns out is about right over the period we looked at), then clearly that is context for a more recent valuation number that can’t be ignored. Or, simplifying even more, you wouldn’t feel as good about the shirt you bought for 20% off when your colleagues tell you it had been marked at 30% off until recently. Indeed, decreasing the discount is effectively putting up the price.

The more subtle aspect of valuation is the time period over which it might be hoped to pay off. If you buy something cheap you may feel good about that at the time. But if it stays cheap forever you have a problem. And, from what we could tell, looking at Chinese equity market valuation history and subsequent returns, two good working assumptions on valuations are that; they are only part of the story (many things impact equity markets), and that they seem to pay off over longer time periods (the relationship between valuation and subsequent return seems weak, but strengthens as the holding period lengthens).

So, the bottom line is that we like valuations very much – but we like them in context. Try different metrics, compare them to different markets, contextualize them with history, and stay patient.