Each year at the Inside ETFs conference, my old friend Matt Hougan and I give our “State of the Union” presentation. It’s a chance to pause and really think about the year that was (2019 in this case) and make some observations about how the market is changing, and specifically how the wealth management and ETF markets are evolving.

The key theme from this year was simple: that for most investors, investing is a solved problem, and yet actually providing advice is becoming the true grand challenge in financial services.

The State of Play

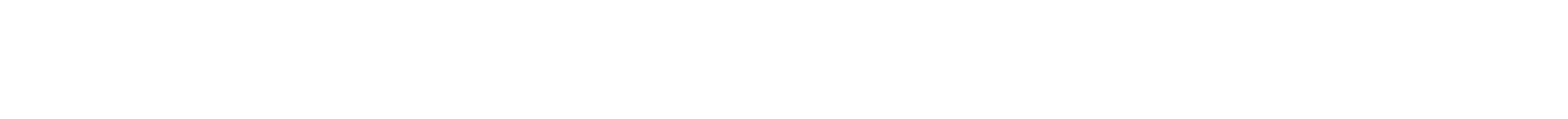

2019 was another incredible year for ETFs. $326 billion in net new money came into ETFs, evenly split between equity and fixed income. At the same time, traditional mutual funds had nearly $100 billion in outflows. Bolstered by buying from all classes of investors, that puts the tally since the global financial crisis here:

That astonishing $2.6 trillion in net flows means investors have voted with their wallets to the tune of $1 billion a day since the crisis, or $45,000 per second that the market’s been open. It hasn’t mattered whether the market is up or down, the flows have continued. This continued movement into the superior structure of ETFs means that it’s only a matter of time until ETFs cross mutual funds in total assets.

This model, which I’ve been running for over a decade, hasn’t changed much over time. Currently we’re predicting asset crossover in roughly 2027, and 10 years out, we’re looking at a $25 trillion ETF market. That may seem like a lot, but it was only a few years ago that $5 trillion seemed like an impossibly large number.

The reason for this growth — both past and predicted — is simple. ETFs now exist to cover virtually every investable asset class in the world, usually providing low cost, passive exposure. Whether you’re a believer in active management or not, the math is inarguable. The latest SPIVA report from Standard and Poor’s suggests that 85% of active large-cap managers underperformed their bogie in the equity space. Worse, the likelihood that a top performing manager in any given year repeats that performance for the next two years is just 8%.

It’s impossible to justify chasing these kinds of odds, when the world’s cheapest ETF portfolio is currently sitting at roughly 0.03% in aggregate expenses.

This simple portfolio, for what its worth, would have trounced the average endowment in any of the past few years. Last year, the average endowment returned under 6%. And this incredible decline in the cost of getting institutional-caliber exposure is really just the beginning. 2019 was the year commissions essentially disappeared. And even custody relationships are being disrupted by upstart firms like Altruist looking to remove even those small costs from an advisors business.

So that’s why I consider investing largely solved. Sure, there are plenty of things that advisors still need to pay attention to. ESG products will continue to flourish, and many investors will genuinely care and want to adjust their strategies. You’ll need to get smart about that. Cryptocurrencies and alternatives will become more important in the hunt for non-correlated assets. The crushing fee war means you need to pay very close attention to things like where your client’s cash is parked (because hidden fees are definitely going to be the new black.

But fundamentally, the games over.

The Grand Challenge

Because I’m a huge nerd, I tend to think of things in math problems, and I think the interplay between investing, and actual advice, is a bit like the P=NP challenge in math:

In it’s simplest terms, the P=NP question looks at two classes of math problems. One class, like a rubiks cube, is very easy to check (a 4 year old can confirm if you’ve done it right, and is actually pretty easy to solve, mathematically. Importantly, it doesn’t really matter how big you make the rubiks cube, the math scales with it. The other class of problems — called NP problems — are still super easy to check (like a sudoku puzzle) but there’s no quick math to solve them. For the most part, you have to brute force your way to a solution, and if you make the problem bigger (say, 10×10 blocks vs 3×3 blocks) the math gets blisteringly complex incredibly quickly.

To me, investing is a P problem. We know how the math works, and once you have a portfolio modeled, you can scale that to any number of clients, or any amount of money. Advice, however, is a pain in the neck. Human beings are messy. Worse, our behavior almost always gets in the way.

Depending on whose methodology you look at, investors real world performance lags their theoretical potential performance by anywhere from 1-6% a year. Advisors know this. In fact, one of my favorite quotes I’ve heard from an actual, real world advisor brings it home:

Depending on whose methodology you look at, investors real world performance lags their theoretical potential performance by anywhere from 1-6% a year. Advisors know this. In fact, one of my favorite quotes I’ve heard from an actual, real world advisor brings it home:

If only we could get rid of all those pesky clients with their illogical whims and desires and reactions, right? But that’s also precisely why advice is so important. While the portfolio may be somewhat rote, if your clients are just coming to you for an asset allocation, chances are your going to lose them to a roboadvisor platform from the likes of Vanguard or Schwab eventually. Instead, smart investment advisors are focusing on the “advisor” part of their moniker, helping their clients navigate home ownership, education planning, career growth and more.

How you get paid for those kinds of services will likely be the next big source of disruption, because, like an NP problem, real advice isn’t scalable. You can spend hours helping one client navigate a potential career change, and that does nothing to help you with the next client’s college funding nightmare. The next generation advisor is going to have to rethink their AUM-based fee model, whether that’s augmenting it with retainers, providing “family office” type services or simply charging by the hour.

The model is changing — and will continue to change, probably faster than we expect. According to Cerulli Associates, 1/3 of all the advisors currently working will be retiring in the next 10 years. As the next generation of advisor rises up to replace them, their inheriting a business deeply in flux, but also one that’s about as interesting as any I can think of: actually helping people.