By John Eckstein, Astor Investment Management

The last act of the Quantitative Easing play

If the global financial crisis was a play, the Fed is getting ready to begin the last act. This fall, the extraordinary support given to the US economy likely will begin to unwind. Such a significant move raises the question: What is the outlook for the Fed for the rest of the year and into 2018?

In large part, of course, it depends on the evolution of the US economy. But by closely reading Fed statements, we can see the broad outlines already. It seems likely that the Fed’s balances sheet will be substantially higher and interest rates substantially lower than would have been considered normal before the crisis.

How we got here

Ten years ago this summer, two Bear Stearns hedge funds failed. These were telltale signs of the imbalances that dominated the US financial markets, whose unwinding would lead to the global financial crisis. Twinned with the bursting of the housing bubble, the financial crisis plunged the US into the worst downturn since the great recession. The Fed started cutting interest rates in September 2007; rates reached 0.25 in December 2008.

The Treasury and the Fed enacted an alphabet soup of special programs (TARP, TALF) to buy assets and shore up this or that bulkhead in the leaky boat the financial system had become. But what about the broader economy?

At the time, it was widely thought that short-term rates could not get below zero, the so-called Zero Lower Bound. As the effects of the global financial crisis have lingered around the world. we have learned that, unfortunately, modestly negative interest rates are in fact possible.

But in 2008 the Fed was not ready conceptually to impose negative interest rates on the US. That left them with an economy crying out for help, but their preferred tool already fully employed. In other words, the Fed had already floored the gas pedal, but still needed to add power. What to do?

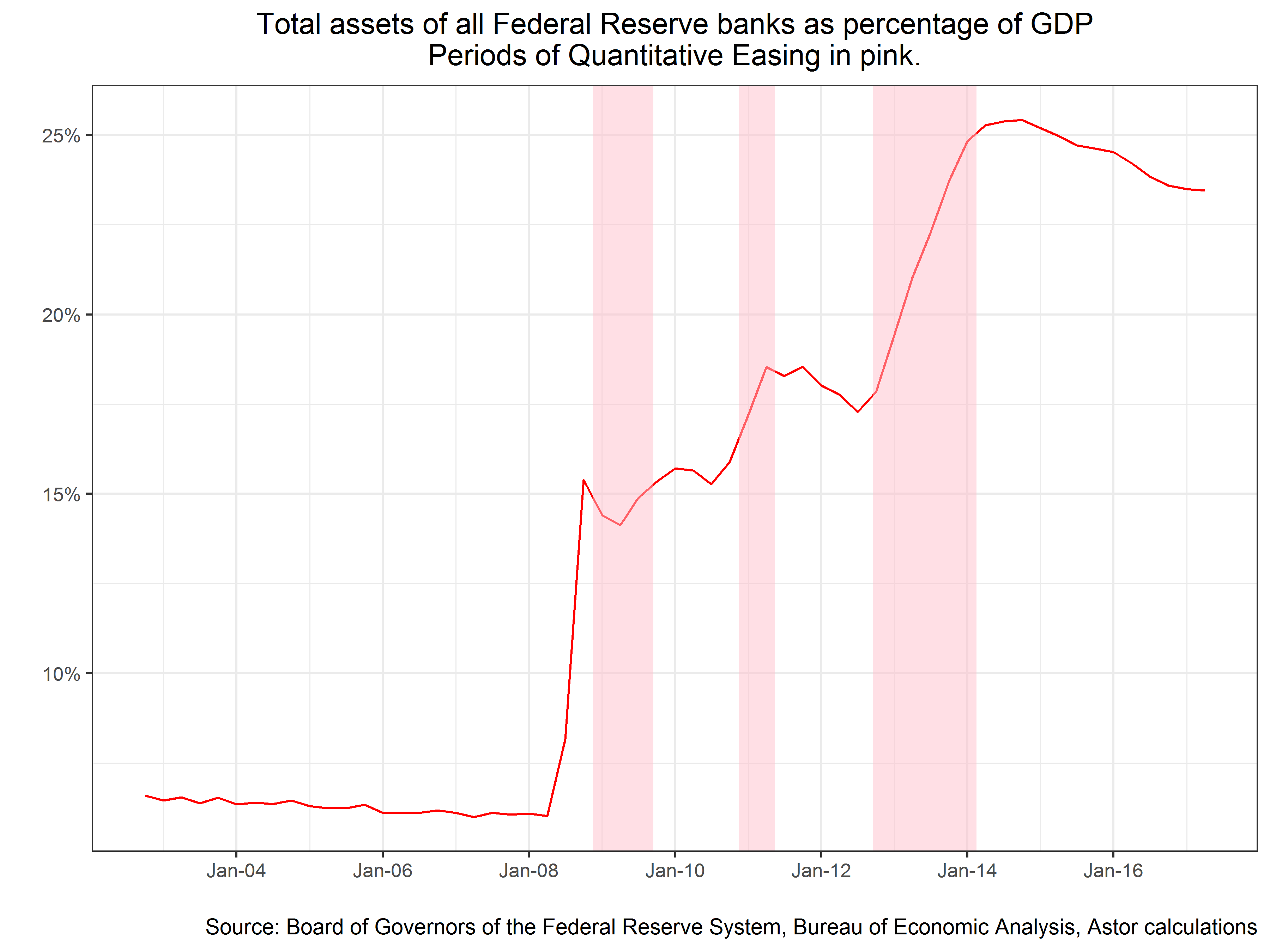

They settled on the related concepts of large-scale asset purchases combined with forward guidance on the level of interest rates. Forward guidance relates to language from the official FOMC statements and speeches about the need to maintain a highly accommodative stance for an extended period of time. Paired with this were large-scale asset purchases known as Quantitative Easing (QE). The Fed expanded is balance sheet dramatically as can be seen in the chart below.

This shows the size of the Fed’s balance sheet as a fraction of GDP. Before the crisis (marked in pink), the Fed had a much smaller balance sheet as a percentage of yearly output than it does today. The substantial expansion in the balance sheet occurred when we were years into the recovery.

Where is the balance sheet going?

While the Fed has not added to its balance sheet since 2014, it has been reinvesting the interest and principal payments received to maintain the balance sheet at a steady level. Direct additions to the balance sheet as a tool of monetary policy are fairly new in the US, and, in our view, the Fed is not completely sure how allowing the assets to run off will affect the economy. Hence, the long wait to begin to unwind until the Fed was fairly assured that growth is robust.

In my view, someday soon, likely this year, they will cease reinvesting all principal and interest payments and instead reinvest only the amounts that exceed a sliding cap. (See the FOMC’s deliberation over the timing in the minutes of the June meeting). The cap will start at $10 billion a month, so in the first month the Fed will reinvest whatever the principal payments are, less the $10 billion they are going to allow to roll off. The cap will rise quarterly to $50 billion. (The Fed’s most recent comment on normalization can be found here.)

Given those numbers, the Fed’s balance sheet will shrink by about $300 million in the first year and $600 million in subsequent years. These are large numbers, but the chart below shows that the Fed’s balance sheet went from about $0.8 trillion to about $4.5 trillion today. But where will the balance sheet settle? In our view, it will likely be much larger than a linear extrapolation from the old line. Former Fed Chair Ben Bernanke has cited (in this blog post) several reasons why the balance sheet may need to be around $2.5 trillion by the middle of the next decade – similar to estimates at this Fed study.