By Brandon Bischof and Tom Hardin, Canterbury Investment Management

The Coronavirus has been sweeping the world. It has affected more than 70,000 people, killing over 1,700. Most recently, there has been 15 reported cases in the US. The financial news seems to attribute every slight market pullback to this ongoing event. The question is: How much, if any, does an event like the Coronavirus have on the financial markets?

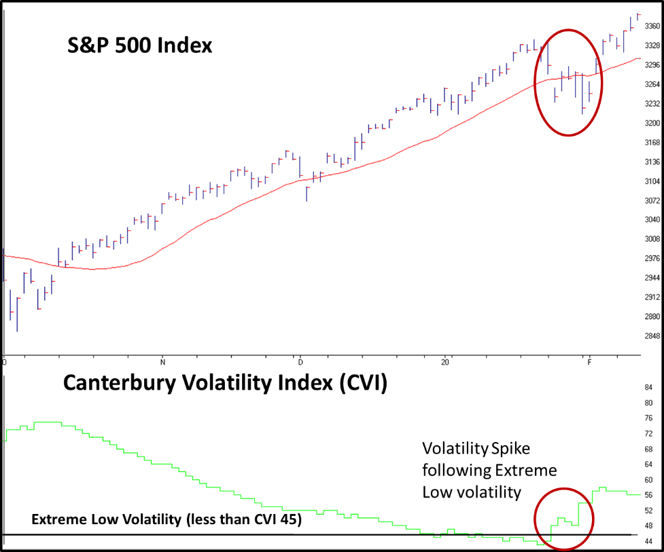

The S&P 500 moved up in a very consistent and orderly manner, with extremely low volatility, from about the second week of October, through January 23rd. We have written many times about our evidence showing that periods of “extreme low volatility” are typically resolved by one or several outlier days of about 1.0% or more. Friday, January 24th was down almost (-0.9%) and the following Monday was down (-1.6%); Tuesday +1%; a week later February 2nd up +1%; the next day +1.5%; and then the next +1.1%.

To summarize, the S&P 500 hit a new high on January 21st at 3,325.54 and then registered another new high, 9 days later at 3,334.69. Of those 9 days, 6 of them qualified as outliers. In fact, there had not been a one-day outlier in 71 trading days prior to January 24th, and then there were 6 days, out of 9, that qualified as outliers. In total, the S&P 500 experienced a minor pullback of (-3.12%). A few days later it was back to a high point as if nothing had happened. Interesting.

Source: AIQ Trading Systems

So, why did the rare 6 outlier days occur, all clumped together? Did the news of the spreading Coronavirus cause a spike in volatility, or was it just a random piece of news that just happened to occur when the market’s volatility was squeezed down to a point that outliers were going to occur anyway? Was the rally back to a new high due to an easing of worry, or was the rally just typical of the current bullish market environment?

News does not drive the markets. News can drive market noise, or maybe a series of outliers are set to occur either with, or without a news event. The market’s reaction to a news event is largely dependent on the state of the current market environment. We have seen this many times before. Market history rarely repeats itself, but it does often rhyme. The current event we are seeing (Coronavirus) is very similar to a market event we saw back in 2014: Ebola.

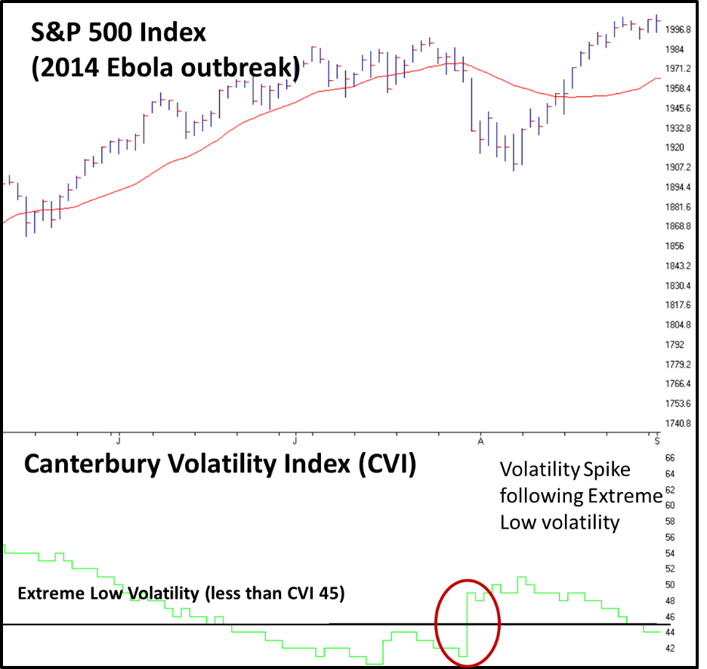

Back in July of 2016, we wrote a weekly update centered around the 2014 Ebola outbreak and extreme low volatility. Referenced in that update were headlines such as “It could Change the Economy of the World (Bloomberg Markets, Sept 25, 2014)” and “Wall Street Tumbles on Ebola Fears (Wall Street Journal, Oct 1, 2014).” The events leading up to Ebola were also similar:

Excerpt from the Canterbury Weekly Update on 9/22/2014:

Keep in mind that extremely low volatility will sometimes bring the “one day outlier” we have discussed many times in the past. Markets are supposed to move. Slow markets mean complacency among investors. Complacency will sometimes end with a knee jerk reaction to an unexpected short-term event. The important point to remember is that such moves are just part of the random market noise and will have little impact on the overall trend.

From September 25, 2014 to October 15, 2014, the S&P 500 saw a volatility spike and a few outlier days, following a period of extreme low volatility.

For something that was supposed to “change the economy of the world” and an event that caused Wall Street to “tumble,” the S&P 500 had a peak to trough decline of -7.40%, and then rebounded to a new high over the next twelve days. Ebola was simply the news that caused some pent-up pressure from extreme low volatility to be released.

Source: AIQ Trading Systems

There have been several other newsworthy events in history that had very different impacts. For example, the JFK assassination, which had massive historical implications, occurred during a bull market. At that time, the market dropped 3% and then rebounded to a new high a few days later. Brexit, which occurred back in 2016, also happened during a bull market, and again the market dropped 3% and then rallied back like nothing had ever happened.

On the other hand, events like President Eisenhower having a heart attack (and surviving) or 9/11 both occurred in a bear, or transitional Market State environments. The markets were already nervous and jumpy. An unexpected piece of news was likely to cause a much bigger move just because the volatility was already high. The impact of these events had less to do with their severity and more to do with the overall market environment at the time.

Bottom Line

News events can drive market noise, but the impact of the event is largely dependent on the preceding market environment. An event like Ebola, and now the Coronavirus, was preceded by extreme low volatility and caused a release of the pent-up pressure. Following each volatility spike, the market went right back to the normal and efficient environment that preceded it. This is very typical of low volatility environments. On the other hand, an unexpected news event that occurs during a more volatile market environment will have a bigger effect on price change. Such an event can have a larger short-term impact or can trigger a move that would exceed a normal “correction,” defined as -10% decline from the previous peak.

Canterbury’s studies show that an unexpected news event, during a bull market, will not cause an immediate shift to a bearish market environment. Markets do not go from a low volatility bull market to a high volatility bear market overnight. A change in market environment requires a process.

Markets are dynamic. They go through many different phases ranging from rational to irrational behavior. These market phases will produce extended periods of extremely low and periods extremely high volatility.

Common sense would tell us that a stagnate buy, hold and rebalance portfolio management strategy, like the traditional fixed strategic allocation methodology, is doomed to eventually fail. In other words, dynamic markets, like changing outdoor temperatures, require an adaptive process in order to maintain a consistent temperature indoors, or in the case of portfolio management, an adaptive process to systematically adjust the portfolio’s holdings in order to maintain stability through all market environments… bull or bear.

This article was submitted by Canterbury Investment Management, a participant in the ETF Strategist Channel.