Financial markets have begun to price in the possibility that the U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed) will reduce, or taper, its purchases of U.S. Treasury and mortgage-backed debt. On the surface, one would expect that a very large purchaser of U.S. Treasuries stepping back from that market would lessen demand, cause prices to slip, and yields to rise. Indeed, long-term U.S. interest rates have again begun to move higher. We think that these interest rates will continue to move higher over the coming 12-18 months in fits and starts.

However, we think that there are powerful forces in the global financial system that will keep U.S. long-term interest rates from breaking out significantly above the 3% level. As a result, we expect long-term interest rates to maintain an average level that is less than what we saw during the previous business cycle.

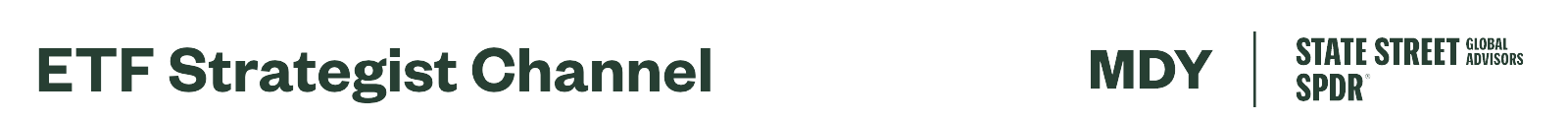

During the initial stages of an economic recovery, such as we are in today, the yield curve has historically risen to approximately 3% (exhibit 1). The yield curve, or the difference between short-term and long-term interest rates, reflects the market’s expectations for economic growth and inflation. Prior to a recession, long-term interest rates tend to fall below short-term interest rates, causing the yield curve to invert. When this occurs, it suggests that the markets are pricing in economic contraction, or recession, rather than growth. Conversely, when the yield curve is positive and long-term interest rates are higher than short-term interest rates, the market is reflecting expectations for economic growth and inflation. These forces are most pronounced during the initial recovery stage of a business cycle.

We think that the U.S. economy is currently in such a recovery stage. However, we also think that there are powerful forces at work that will keep the 10-year Treasury yield from spiking to levels seen during the previous business cycle. As historically low interest rates keep a lid on debt service costs and limit mortgage interest rates, we view this relatively muted yield outcome as a strong positive for the U.S. economy.

These forces tempering long-term rates include the massive amount of cash, or liquidity, sloshing around the global financial system, as well as the relatively low cost for global institutional investors to purchase U.S. Treasury bonds, which also supports prices and limits yields.

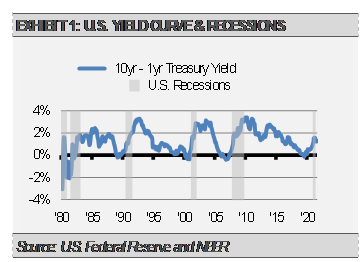

Historically, the 10-year U.S. Treasury yield traded within a range relatively close to the 10-year German Bund (exhibit 2). However, as central bank policies began to differ in the early-to mid-2010s, these yields began to diverge.

Around that time, the Fed began to increase short-term interest rates as the U.S. economic recovery from the global financial crisis solidified. Meanwhile, the European Central Bank (ECB) was struggling to deal with the European debt crisis, including the Greek default. Contrary to the Fed’s policy tightening, the ECB kept euro zone short-term interest rates pegged near zero.

The U.S. dollar strengthened versus the euro and the cost for foreign investors to hedge their U.S. dollar exposure increased. When an investor hedges foreign currency exposure, they are effectively borrowing in that foreign currency and lending in their own. The difference between these two interest rates influences the cost of the hedge. As short-term interest rates between the U.S. and the euro zone diverged, costs to hedge the U.S. dollar for foreign investors increased. This increased hedging costs explains much of the difference in yield between long-term U.S. Treasury bonds and the German Bund.

The expense to hedge currency essentially negated the increased yield a foreign investor would receive for owning U.S. Treasuries versus the Bund.

We are in a different situation today. In response to the economic impacts of the global pandemic, central banks around the world, including the Fed, lowered short-term interest rates.

With short-term interest rates expected to be lower for a longer period of time, the costs for foreign investors to hedge their U.S. dollar exposure has declined. Today, foreign institutional investors can purchase 10-year Treasuries, capture a higher yield than their domestic sovereign bonds pay, and hedge their U.S. dollar exposure at a nominal cost.

This relatively attractive situation for foreign institutions should result in increased ownership of U.S. Treasury debt by foreign institutions, thus replacing the demand for U.S. Treasuries by the Fed as they step down their purchases. Foreign demand for U.S. Treasuries should help keep a lid on long-term U.S. interest rates. We expect this situation to persist until the Fed has sufficiently increased short-term interest rates and the divergence between short-term interest rates in the U.S. and foreign countries again appears.

While we do expect the 10-year Treasury yield to move higher, we think the average rate during the current business cycle will be lower than what would have been the case without so much foreign demand and well below what we saw during the previous business cycle. Instead of averaging 3% or more, we may see an average of only about 2.5%.

DISCLOSURES

Any forecasts, figures, opinions or investment techniques and strategies explained are Stringer Asset Management, LLC’s as of the date of publication. They are considered to be accurate at the time of writing, but no warranty of accuracy is given and no liability in respect to error or omission is accepted. They are subject to change without reference or notification. The views contained herein are not be taken as an advice or a recommendation to buy or sell any investment and the material should not be relied upon as containing sufficient information to support an investment decision. It should be noted that the value of investments and the income from them may fluctuate in accordance with market conditions and taxation agreements and investors may not get back the full amount invested.

Past performance and yield may not be a reliable guide to future performance. Current performance may be higher or lower than the performance quoted.

Data is provided by various sources and prepared by Stringer Asset Management, LLC and has not been verified or audited by an independent accountant.