By Aurour Investments

We recently watched a TED talk by fiction author John Green. He opened his talk by discussing Agloe, a made-up town in New York that he used in his book Paper Towns. Agloe was created by the cartographers who made Esso maps in the 1930s as a means of detecting future plagiarism. If Agloe found its way onto another cartographer’s map, they would know their work had been stolen. And when two decades later the town name appeared on a Rand McNally map, the cartographers naturally threatened to sue McNally. In fact, however, it turned out that after more than 20 years, Agloe had indeed become a landmark. A general store had opened right on the spot, and seeing the name Agloe on an Esso map, the proprietors named it Agloe General Store, legitimizing the “paper town.”

In this tale of cartographers unintentionally helping to create a landmark, we see an interesting analogy to today’s global economy.

The Federal Reserve and its central bank brethren have moved interest rates to nearly zero as a means of reigniting economic activity. In so doing, they have unintentionally built an ecosystem dependent on low financing rates, which has caused some to claim they have given up on their main mission of price stability.

This newsletter will highlight one example of this low-rate dependency, as well as a potential change in the environment we should all watch, and last, it will touch on an unintended consequence resulting from the low-rate environment.

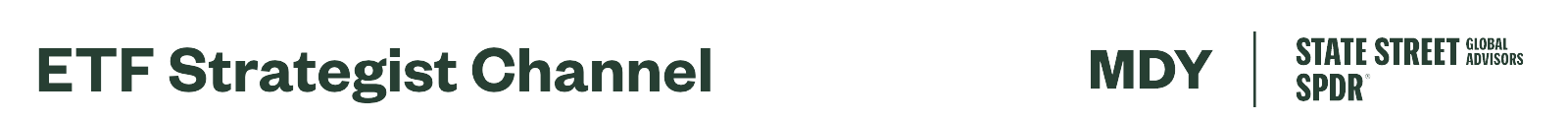

Headlines have been filled with the news that the largest property developer in China, Evergrande, is struggling with very significant debt and low liquidity. In 2021, Evergrande’s stock price has declined 85% as the markets fear an eventual default. With more than $300 billion in liabilities, should there be a bankruptcy, it would be one of the largest on record.

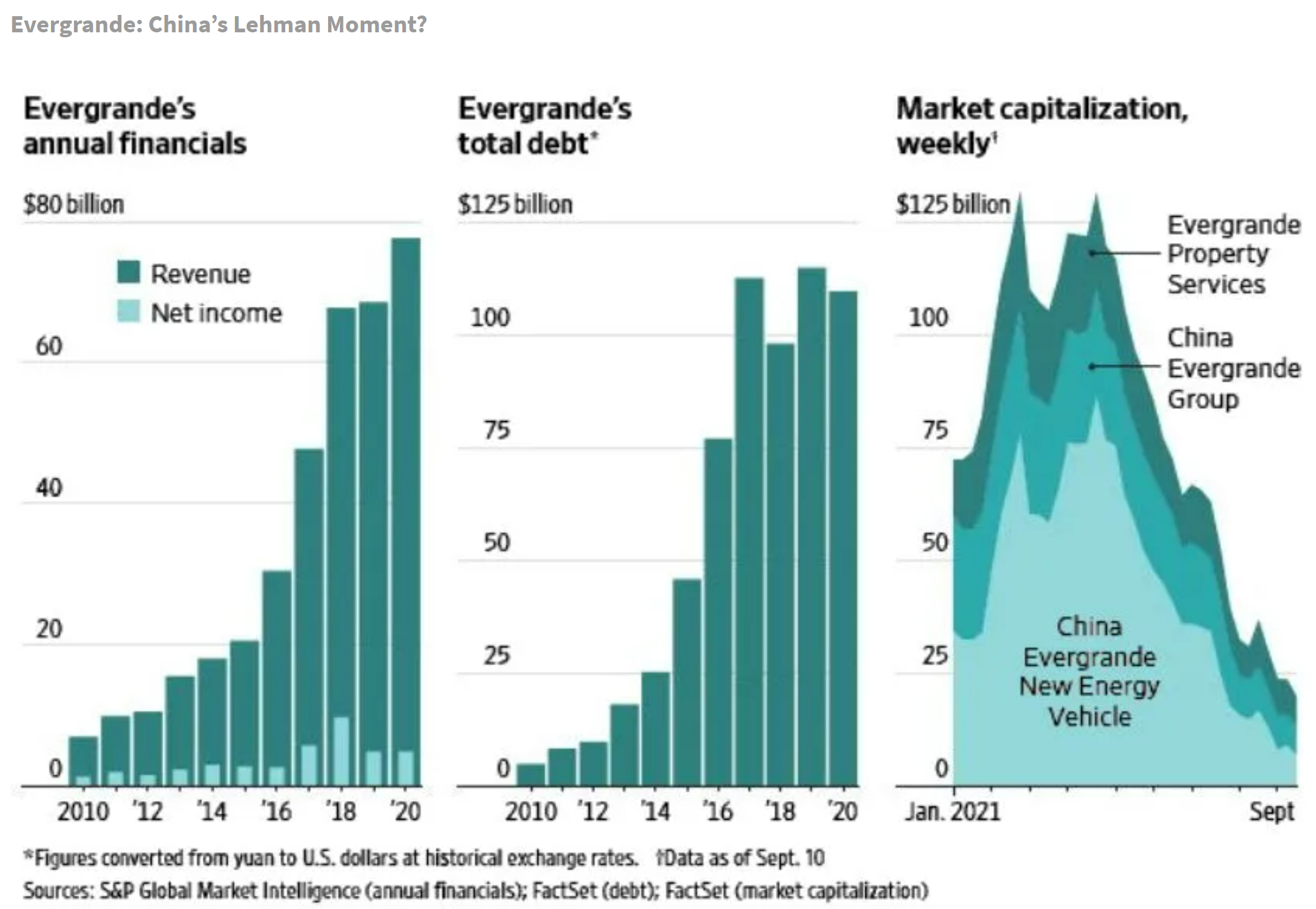

To put such a default in context, Lehman’s bankruptcy resulted in a bond default of $150 billion. Now, Evergrande’s potential corporate bond default would likely come to less—approximately $200 billion of their liabilities are in buyer deposits and supplier payables—but no matter, the bond default would still approximate $90 billion, almost four times the largest default experienced since 2011.

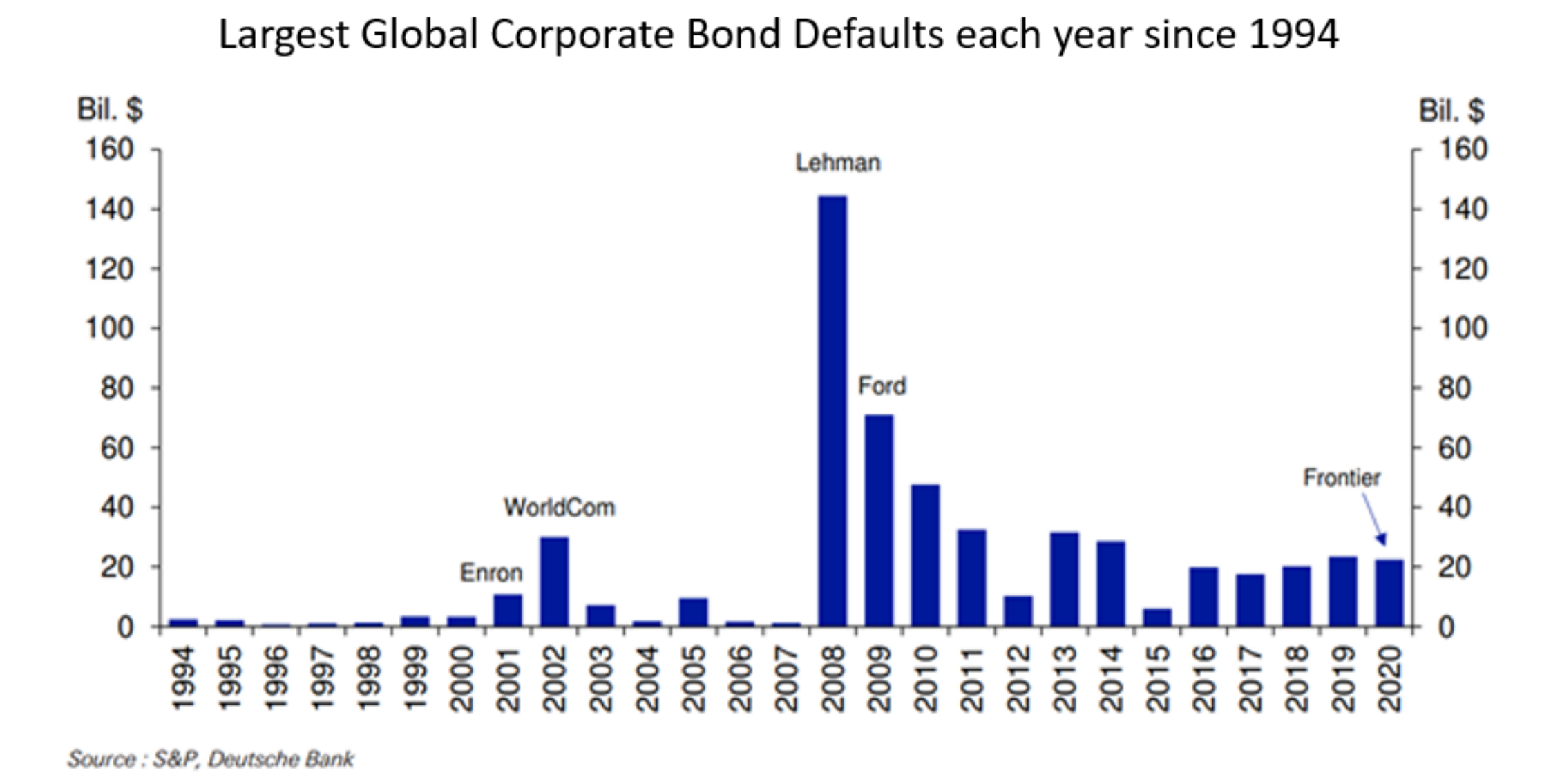

Currently, Evergrande has missed their September payments on U.S.-dollar denominated bonds. Looking at what’s due in future monthly payments suggests the problem will only get worse.

Many are asking if this is China’s “Lehman moment.” Is this the domino that falls and topples other fragile institutions causing greater value destruction and liquidity constraints? We don’t think this is quite that bad. Lehman was uniquely situated to cause collateral damage because, as a global investment bank, it served as a middleman in transactions amounting to trillions of dollars across the globe. Their default spread across large swaths of global GDP. Lehman’s downfall also happened very quickly, and the U.S. regulators lacked the authority to thwart the collapse.

Evergrande’s troubles are not as far-reaching as Lehman’s, and they have been known for years. Also, China, with its controlled economy, can likely address the property developer’s liquidity issues through its state-owned enterprises.

Just because it is not likely a Lehman moment doesn’t mean the boomtown mentality will hold up within China. Asian property developers, such as Sunac and Greenland (no relation to the country), are experiencing funding shortages while there is concurrently a slowdown in home sales in China. If sales wane, prices likely will fall, too, and the results could be uncomfortable for many.

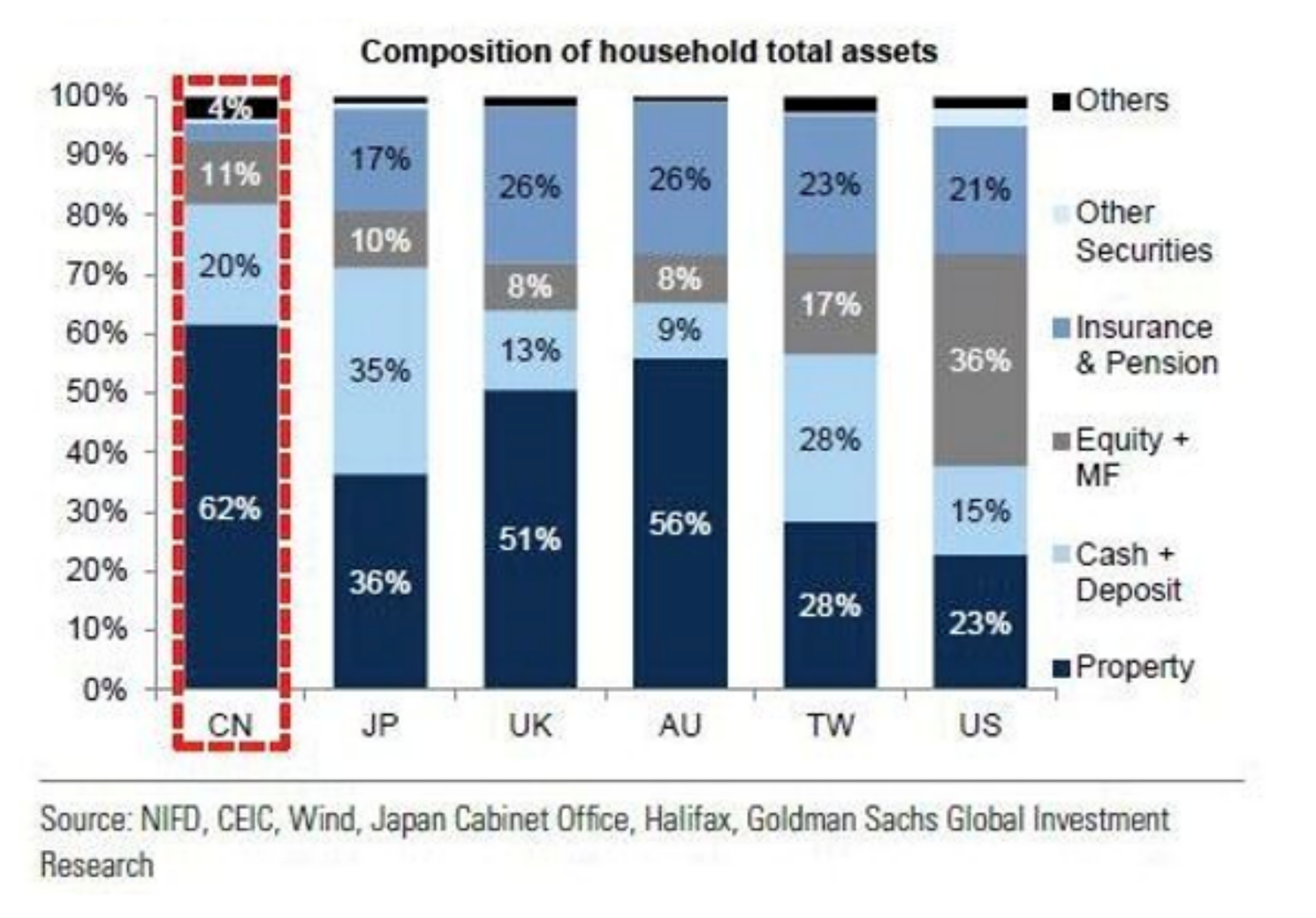

China’s economy and the wealth derived from it are highly tied to the real estate market. Unlike in the U.S., where housing assets represent about a quarter of household wealth, in China they represent more than 60% of wealth. Housing and the industries tied to it represent about a quarter of China’s GDP. We have discussed the implications of the wealth effect on U.S. consumption, where declining wealth leads to declining consumption. One should assume the same is true for China’s consumers.

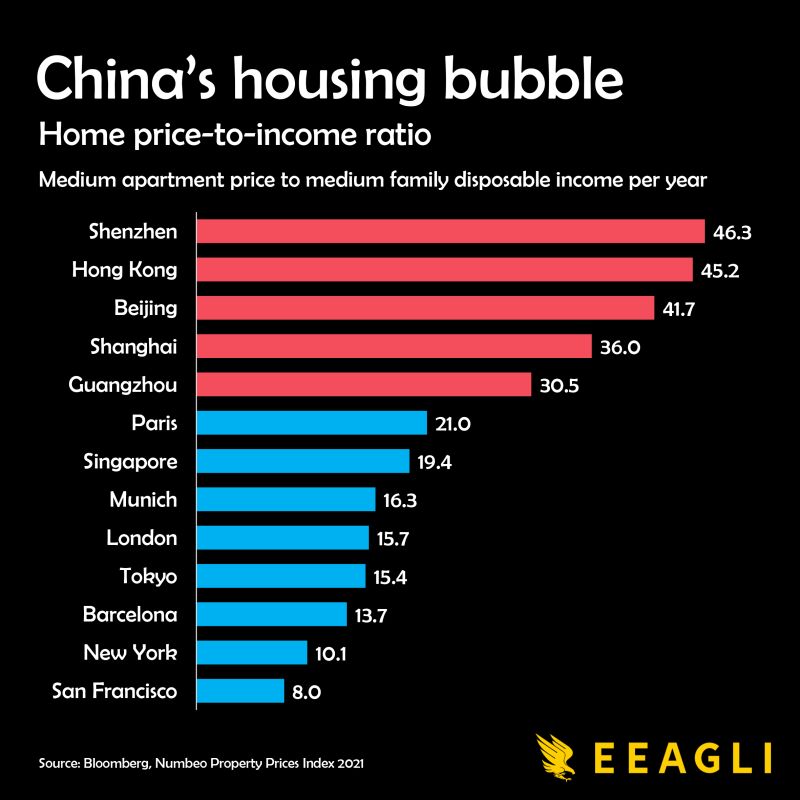

respect to pricing, China’s housing market looks fragile. We were young when it burst, but we still remember the many justifications given for the bubble in Japanese real estate in the late 1980’s, and we hear the same reasons today being used to describe the property situation in China. Economic activity and low rates can create a nice backdrop for optimism, but long-term reality may lead to some sorrow. Chinese home prices as a percent of income are the highest in the world. Low rates allow buyers to think about how much in monthly payments they can afford. However, if rates start to move up, householders’ attention may well move to how much debt they have tied to an expensive asset.

Interest Rates

The push for lower and lower interest rates appears to be in the rearview mirror. The rapid rise in inflation and concerns that it will linger has contributed to global central banks taking the foot off the accelerator and at least modestly tapping the breaks.

Rate hikes are now outpacing cuts (albeit off a low number). Some will see this as a tepid move to a more normal rate environment, but we believe it warrants attention because the global investment markets have become accustomed to easy money. The incremental tightening of money availability may be considered by some to be a radical change. Financial leverage is high and modest shifts in cost of debt and its availability could bring about dislocations to global markets.

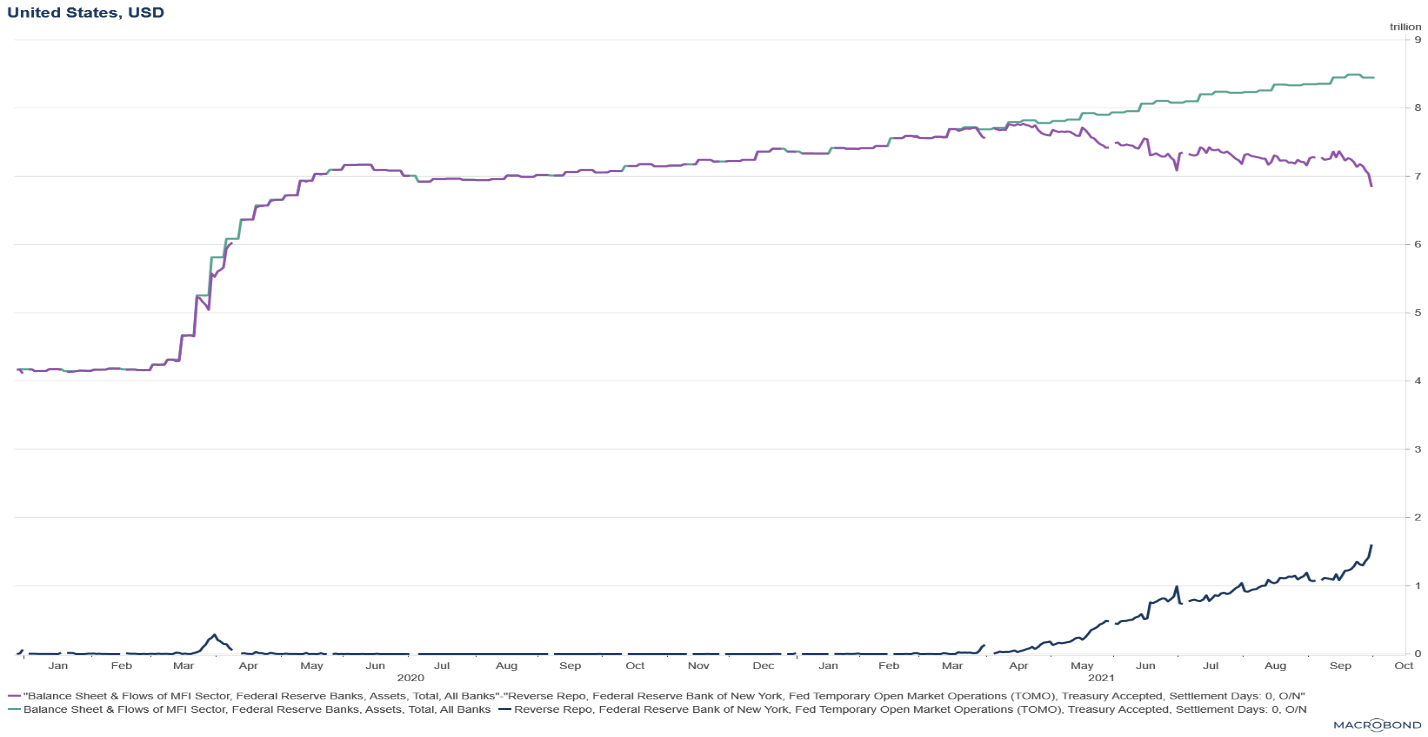

The chart above looks at liquidity as defined as the Federal Reserve balanced sheet minus the money that is being placed back with them as a means of finding a safe place to store it. The continued growth in the Fed balance sheet is well known; less publicized is the amount of money going back to the Fed for safe keeping. The purple line is the net liquidity offered by the U.S. central bank. It peaked in April of this year, and we have been experiencing a declining liquidity environment with the rate of decline accelerating.

Keep in mind that the Evergrande troubles were showing themselves long before the modest U.S. liquidity drain shown above and before rate increases were becoming significant.

Blockchains and Digital Assets

The Agloe analogy really hit us as it pertains to the blockchain ecosystem. The unintended consequence of a few cartographers brought about the birth of a real place on the map.

Central banks, in their attempt to stabilize economies, have caused some to create a new town that is independent of central bank dictates. The low-rate environment has brought about concern that governments are in a race to debase their currencies to placate their populaces. The fear has generated a desire by some for an asset that has finite units and therefore a hope that it would retain its value relative to fiat currencies. Bitcoin is the poster child. We are not believers in this fear, at this point, as central banks are still independent institutions that continue to state their main objective of providing price stability. We will see if they can regain trust.

However, the bitcoin phenomenon has birthed a technology idea (blockchain) that has gathered adopters for purposes other than dollar-replacement assets. Blockchain, as a technology, intrigues us as we witness the development of new business models because of it. As personal computers moved computing power to the individual and away from the glass walled mainframes, we see an opportunity for blockchain technologies to drive a continued evolution to decentralization.

The caveat to this intrigue is that we are early, and history has not been kind to the first movers. In the late 1990’s, the internet was promising but nascent. We remember the pitch of many brokers that one should buy a basket of names to participate in the long-term theme of the internet. The idea was to build a portfolio of internet leader that included companies such as JDS Uniphase, Worldcom, Corning, Sun Microsystems, AOL, Yahoo, Cisco, Intel, VerticalNet, Pets.com, Netscape, etc. Many of these were monsters in their respective spaces yet went on to become lackluster performers or outright value destroyers. The returns did not match the enthusiasm and the benefits did not accrue to many of those companies.

We offer this up as an example that optimism on an idea does not always reflect positive future returns to current players. Yet, the optimism is real and some new things are here to stay. Optimism can bring about a new order upon which life is lived. We will continue to investigate the opportunities and threats that may result from blockchain technologies.

For more news, information, and strategy, visit the ETF Strategist Channel.