By Gary Stringer, Kim Escue and Chad Keller, Stringer Asset Management

There is no Trump economy, just as there was no Obama economy. In fact, no administration owns the U.S. economy. The people of U.S. own our economy and decades of historical data make this point very clear.

The U.S. has and will continue to have an economy based on capitalist principles. These principles have been in place since the country’s founding and have been upheld by the Supreme Court when challenged, most famously when the Court struck down significant parts of Roosevelt’s New Deal as unconstitutional.

Despite messaging that lays the success or failure of the U.S. economy at the foot of politicians in Washington, DC, the historical data shows that it is individual decisions by the people that drive economic prosperity.

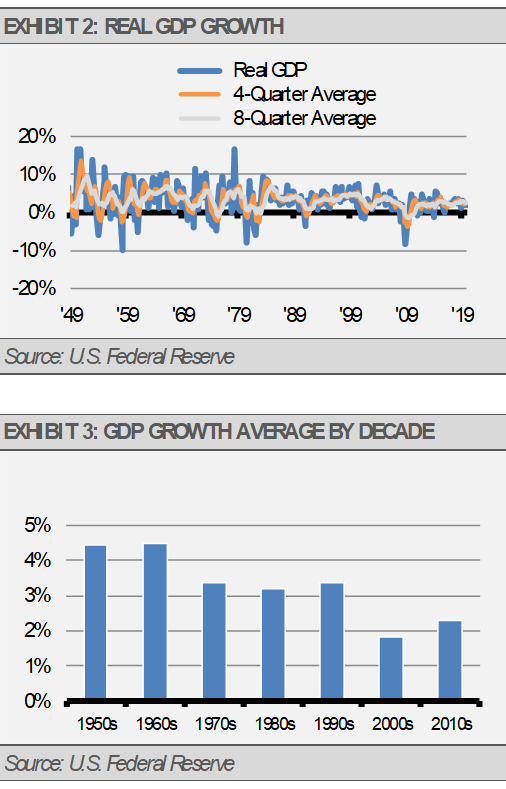

For example, the St. Louis Federal Reserve publishes a wealth of helpful historical economic data. In particular, the St. Louis Fed publishes GDP growth data, the broadest measure of the pace of growth for the U.S. economy, which goes back to July 1947. Since then, we have seen Republican and Democratic presidential administrations come and go. Throughout that history, we can identify a few trends, however, changes in economic growth by administration is not one of them. It turns out that the economy is bigger than what happens within the Washington beltway.

As the tables below shows, there is not strong correlation between the party in the White House and the pace of U.S. economic growth. There is simply no significant relationship, aside from the strong growth experienced by the three democratic administrations of the post-WWII through the late 1960s period and even this was coincidental.

While it can be argued that different administrations had different issues to work through and some may be more conducive to GDP growth than others, we cannot directly correlate the pace of growth to the Presidency. However, certain trends are prevalent.

Overtime, the pace of economic growth declined and became less volatile. The graph below illustrates this point with quarterly annualized, rolling 4-quarter, and rolling 8-quarter data. Clearly, the pace of growth has also become more muted over the years. This decline might be expected as the rate of labor force growth has similarly declined in recent decades. Additionally, the magnitude of swings in the pace of GDP growth has also fallen, which might be expected as the economy grows, matures, and becomes more stable.

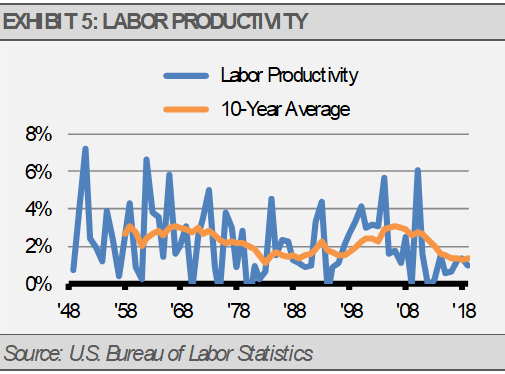

Long-term GDP growth is generally determined by two broad factors: the growth rate of the labor force and the productivity growth of the labor force. The data shows that the growth rate of the labor force has been on a steady decline for decades while productivity growth has been much more cyclical.

Importantly, both factors are driven by decisions and developments coming from the private sector, both at the household level and at the corporate level. For example, the labor force growth rate is heavily influenced by how many children families have and how many adults decide to participate in the labor force. Meanwhile, innovation, which leads to productivity growth, is primarily driven by the corporate research and development. Neither of these areas are determined by politicians.

After WWII, labor force growth may first have been propped up by the baby boomers entering the workforce, and then the number of women entering the workforce in the 1970s and 1980s when the labor force grew significantly faster than population growth. Now that both of those trends have worked their way through the system, the overall pace of labor force growth has declined.

The overall economy is not weaker in our view. It’s just that one of the major factors contributing to the pace of economic growth has shifted significantly and sustainably lower.

Meanwhile, the other major contributor to economic growth, labor force productivity, has been more cyclical. While productivity growth can be volatile year-to-year, rolling 10-year averages paint a clearer picture. As the exhibit below illustrates, productivity growth peaked in the 1960s, fell in the 1970s, was relatively stable through the 1980s and early 1990s, accelerated in the mid-1990s to early 2000s, then declined again over the most recent 10-year period.

Innovation is generally credited with driving productivity growth, yet economists are uncertain as to why productivity growth has exhibited such cyclicality. For example, recent weakness in productivity growth has been attributed to technological innovations focused mostly on digital platforms that do not impact overall productivity. For example, commercial aircraft fly no faster today than they did in the 1960s and since the information revolution and advent of software like word processing, digital innovations have not made our workforce significantly more productive. On the other hand, some economists argue that recent innovations have just not had enough time to become apparent in measurements of the real economy.

Regardless, sustained acceleration of GDP growth will be dependent on an increase in productivity growth now that labor force growth has stabilized at today’s low levels.

Though the media and the political class like to embellish the importance of politics in economic outcomes, the data just does not support those claims. Intuitively, this make sense. A capitalist economy would be expected to be driven by the private sector, inclusive of both businesses and households. It would be inconsistent to think that politics would be a dominant factor, and that is indeed what the data suggests.

As has historically been the case, we can rely on innovations from the private sector, such as those from Henry’s Ford’s assembly line to Bill Gates and Microsoft, to unlock our economic potential.

This article was written by Gary Stringer, CIO, Kim Escue, Senior Portfolio Manager, and Chad Keller, COO and CCO at Stringer Asset Management, a participant in the ETF Strategist Channel.