By Michael Paciotti, CFA

Last thing I remember, I was running for the door. I had to find the passage back, to the place I was before. “Relax, ” said the night man, “We are programmed to receive. You can check-out any time you like, but you can never leave! ” – Eagles, Hotel California,1976

In normal times, if there ever were such a thing, we could discuss traditional methods for central banks to achieve their dual mandate of unemployment and inflation, and then proceed into unconventional methods. At this point, who knows what is normal, conventional or unconventional. After a decade of dealing with imbalances in the financial system, what was unconventional during the great financial crisis seems normal today. It doesn’t mean it is. I’m sure somewhere we can concoct a definition of what is a normal policy approach vs. what is extreme. Everything has costs and benefits.

In the traditional world that seems like eons ago, economies followed a normal business cycle of expansion, peak, contraction, and recession. To have a cycle is normal and healthy. To prevent them, or to not experience them, is not. During peak prosperity, the economy should approach full employment, tight labor markets would cause wages to grow, inflation would creep up, the central bank would raise interest rates to combat inflation, cooling the economy and resulting in contraction. At this point, rates would be sufficiently high so that during recession, they could be cut to the opposite effect. Risk assets would follow a similar pattern of advance, stabilize, decline, and recover. The decline part is important and necessary, as it reminds investors not to get too greedy for fear of the consequence. That consequence keeps asset prices in check and deters bubbles from forming. Problems arise when through policy action, and perhaps more importantly inaction, there are no cycles. The purpose of this quarter’s Market Insights, The Dark Side of Fed Policy is to discuss in greater detail the intended and unintended impacts of central bank policy.

Fed Policy Tools

The primary mechanism for the Fed to achieve its goal of full employment and low inflation is monetary policy. Why? The price of money influences both the supply of credit and the demand for it. As money becomes cheaper (rates go down) people and business are inclined to borrow more. That extra borrowing turns into spending, which drives up the price of goods and services, and subsequently creates jobs. While changing the price of money to influence the supply and demand of credit is the stated intent, this is only one channel for the Fed to transmit monetary policy into the economy. Alongside rates, in 2008, central banks across the globe embarked on a new experiment, bond buying (or quantitative easing). The intent was the same as before…add immediate cash to the financial system. If the Fed buys a bond an investor holds, that investor receives cash today that they wouldn’t have received until the maturity of that bond. They’ve, in essence, pulled cash forward from a timing perspective. That cash rich investor can now spend it or reinvest it (we’ll get to this later) creating an immediate boost to jobs and prices, the same as with traditional interest rate policy.

Effects & Side Effects

The preceding paragraphs described in broad strokes how monetary policy is intended to impact the financial system. By reducing rates for businesses and individuals the Fed creates cash to do other things. Think of it like when you refinance a mortgage. You have the same mortgage balance, but a lower rate resulting in a lower payment and cash in your pocket to do other things. That is at work here as well. The larger impact is that for the same monthly payment (debt service), you can now borrow more money. The additional borrowing capacity created is the intent. Remember in the introduction when I wrote about pulling cash forward from the future to today? Same concept, getting cash now to be repaid later has a boosting effect. The same thing occurs with quantitative easing. The Fed buys your bond, gives you the money now that you would not have been paid for 10 or 20 years. Cash today is spent or reinvested elsewhere. Both are stimulative.

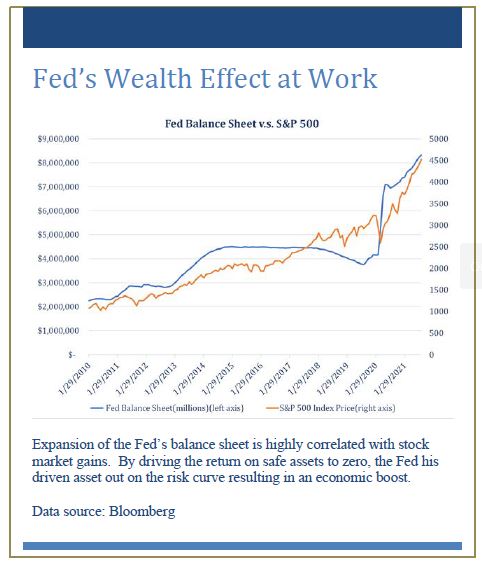

The reinvestment of cash from bond proceeds is an issue I said I would address later and may seem counterproductive until you drill down on the intent. In the mechanics of bonds, yields and prices work in opposite directions. When the Fed creates additional demand for bonds, as a big buyer, prices go up and yields go down. When you decide to reinvest that money, do you seek out a new lower yielding treasury bond to replace your old bond or a higher return somewhere else, such as in stocks or corporate bonds? By making safe assets undesirable to hold (i.e., by reducing the yield), the Fed pushes capital out on the risk curve with the same effect as bond buying. It bids up the price of risky assets, which can then be harvested and spent by consumers. At the same time, reinvestment into risk assets drives down the cost of capital for new issues companies can now finance their operations less expensively). Any mechanism that causes asset prices to deviate meaningfully away from their fundamental fair value is inherently unstable. Stimulative, yes, but at what cost? Potentially the highest cost of all. I’ll get to this later.

The reinvestment of cash from bond proceeds is an issue I said I would address later and may seem counterproductive until you drill down on the intent. In the mechanics of bonds, yields and prices work in opposite directions. When the Fed creates additional demand for bonds, as a big buyer, prices go up and yields go down. When you decide to reinvest that money, do you seek out a new lower yielding treasury bond to replace your old bond or a higher return somewhere else, such as in stocks or corporate bonds? By making safe assets undesirable to hold (i.e., by reducing the yield), the Fed pushes capital out on the risk curve with the same effect as bond buying. It bids up the price of risky assets, which can then be harvested and spent by consumers. At the same time, reinvestment into risk assets drives down the cost of capital for new issues companies can now finance their operations less expensively). Any mechanism that causes asset prices to deviate meaningfully away from their fundamental fair value is inherently unstable. Stimulative, yes, but at what cost? Potentially the highest cost of all. I’ll get to this later.

When bond proceeds are reinvested into stocks, valuations climb, investors feel wealthy, and ultimately spend more money. The Fed has once again pulled cash forward. They have not, I repeat not, altered the economic value of the equation. They’ve just changed the timing. Higher equity valuations create greater returns today at the expense of tomorrow’s returns. It’s a true borrowing from Peter to pay Paul relationship. Take a simple example. Buy a business. The business has $100,000 in annual profits and you pay $1mm for that business. What is your return on investment without selling that business? Its 10%, or 100,000 divided by your $1,000,000 initial investment. What happens if you get the same profit but pay $2mm. Your return becomes 5%. The simple act of paying more reduces your future return. Now, I qualified my example…I said “what is your return on investment without selling it?” The one way to enhance your return is to entice an even greater fool to pay more. Said differently, the valuation keeps rising or the bubble keeps inflating. There is an end to this because eventually you run out of greater fools. The sustainable source of return is from the earnings and cashflows derived from the business, not from enticing the greater fool.

Let me take a moment to describe why the economics don’t change from stimulus by acknowledging and addressing a few points. Theoretically we should, and most times in practice we do, get higher earnings from stimulus. But, the earnings boost is only temporary, as the influx of borrowed funds or harvested equity market gains are repurposed into additional demand. When all the borrowed money is spent, how is the higher earnings trend sustained? It isn’t. You can argue that it creates jobs. True. More jobs equal more spending and even more earnings. Also true. And tight labor markets create higher wages. Again true. But wages translate into higher costs for the business. Higher costs result in price increases, as costs are passed on…aka inflation. What am I describing? A cycle. Stimulate, recover, wages go up, prices rise, then the Fed tightens before contraction and recession. I haven’t changed anything other than manipulating when cash is received, spent, and repaid. It doesn’t change the economics and really isn’t meant to. Fed policy is intended to smooth the peaks and valleys, not change the value of the equation.

Let me take a moment to describe why the economics don’t change from stimulus by acknowledging and addressing a few points. Theoretically we should, and most times in practice we do, get higher earnings from stimulus. But, the earnings boost is only temporary, as the influx of borrowed funds or harvested equity market gains are repurposed into additional demand. When all the borrowed money is spent, how is the higher earnings trend sustained? It isn’t. You can argue that it creates jobs. True. More jobs equal more spending and even more earnings. Also true. And tight labor markets create higher wages. Again true. But wages translate into higher costs for the business. Higher costs result in price increases, as costs are passed on…aka inflation. What am I describing? A cycle. Stimulate, recover, wages go up, prices rise, then the Fed tightens before contraction and recession. I haven’t changed anything other than manipulating when cash is received, spent, and repaid. It doesn’t change the economics and really isn’t meant to. Fed policy is intended to smooth the peaks and valleys, not change the value of the equation.

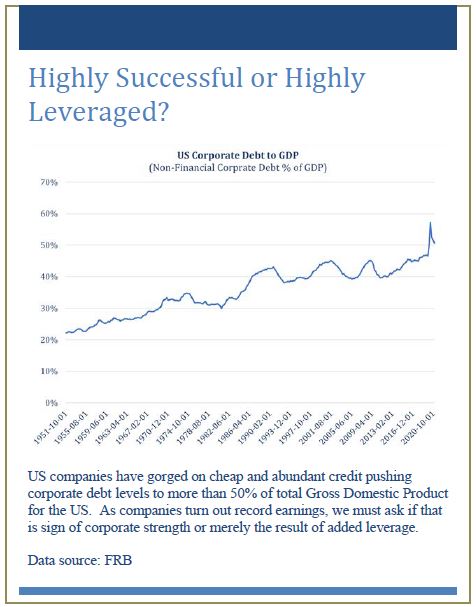

A second side effect that is intertwined and related to elevated equity prices is leverage. Previously, I mentioned that bidding up asset prices reduces the cost of capital. When financing costs decline, this either reduces debt service or opens room for additional borrowing, again just like refinancing your mortgage. The Fed has now encouraged companies to add more debt to their operating structures. While one can argue that this can be done responsibly, it is impossible to argue that more debt on your balance doesn’t create more risk. When you celebrate a company for persistently growing their earnings are they doing that with more debt than they did in the past? If so, the persistency of earnings may simply be the result of financial engineering and increased risk-taking, not brilliance. Leverage is a wonderful amplifier when things are going well and a not-so-wonderful amplifier when they aren’t.

On balance, leverage in the form of direct borrowing by companies is certainly a negative side effect, but it isn’t the only form of leverage. Investors can also borrow money or margin their accounts to add risk. In risk on environments, margin debt increases (see figure to the right). While I would like to believe this is in anticipation of lower returns to follow, and maybe it is by some of the more astute investors, adding margin related risk is probably nothing more than performance chasing and a sign of speculative excess, which adds risk to the system.

On balance, leverage in the form of direct borrowing by companies is certainly a negative side effect, but it isn’t the only form of leverage. Investors can also borrow money or margin their accounts to add risk. In risk on environments, margin debt increases (see figure to the right). While I would like to believe this is in anticipation of lower returns to follow, and maybe it is by some of the more astute investors, adding margin related risk is probably nothing more than performance chasing and a sign of speculative excess, which adds risk to the system.

Related to this, how about when an investor who is conservative is lured by those past returns to add more equity risk to their portfolio, perhaps more than they should? Aren’t they in essence more levered to equity market risk than before the change? If prices move up or down based on the marginal buyer or seller (the next buyer or seller not to be confused with buying on margin), as investor’s increase their equity portfolio allocations this eventually eliminates the marginal buyer. If we extend one step farther than this, what happens when that marginal buyer bites off more risk than they can chew? They become a marginal seller during risk-off environments. I think we can agree both margin buying and adding equity risk through portfolio structure add to the collective risk in our financial system.

The last thing I’ll discuss is potentially the highest cost of all. In my opening remarks I mentioned that cycles are normal and healthy. The stimulate, expand, stabilize, contract phases are all equally important because they provide balance. Without contraction, the pendulum of fear and greed stays swayed toward greed. It’s like driving a racecar with the accelerator stuck to the floor and no brake. There are two speeds: fast and faster. When there is no consequence for risk taking, it tends to reach levels that become foolish. At times, the central bank must be the responsible adult in the room. They need to recognize when everyone has had too much to drink and responsibly remove the punch bowl. If the Fed doesn’t tighten or tighten sufficiently, the speculators never learn the consequences of excess risk taking, leaving prices inflated. When the next crisis arises and the Fed needs to stimulate, they are doing so from already elevated valuation levels.

So why not tighten? Intentionally or not, the Fed has created a series of side effects, The Dark Side of Fed Policy, that stands in their way. The list includes direct on-balance sheet corporate leverage at over 50% of GDP and investor margin balances exceeding levels last seen at the peak of the internet bubble. At the same time, household equity ownership and valuations are at or near record highs. Put it all together and we have record levels of leverage on top of sky-high equity valuations, while households hold more equities, as a percent of their household assets, than they ever have. This has left the Fed the precarious position of if they tighten, they may cause the unwinding of the asset bubble that they created as a policy tool. What would that do to household balance sheets? The truly harmful side effect of Fed policy isn’t even the impact on asset prices themselves. It’s that they may never be able to leave the new normal of unconventional stimulus.

2021 has thus far been another strong year for financial markets. Some will argue the market pullback in early 2020 is evidence of a cycle. I would respond that a one-month decline, even as sharp as that was, is hardly representative of a cycle and was certainly not enough to flush out rampant speculation. If anything, they were emboldened by it and the sharp recovery, as evidenced by the meme and Reddit stock and option buying activity that became popular later that year. I encourage our advisor partners and clients to please be cautious in your approach to planning decisions. I can point to countless euphemisms, but none more appropriate than the advice of Warren Buffett to be fearful when others are greedy and greedy when others are fearful. Very good advice. Given each of the issues that we’ve discussed today, the Fed may be trapped between the proverbial rock of stimulating too much and hard place of popping the bubble and causing the economic disaster they’ve been trying to avoid…essentially, the Hotel California of monetary policy. You can check out any time you like, but you can never leave. Try as they might, tightening sufficiently will be difficult if even possible. The real trick will be what do they do if inflation becomes a serious problem? I’ll leave that for another quarterly Market Insights. Thank you as always for your trust and confidence.

4th Quarter 2021 Market Insights is intended solely to report on various investment views held by Integrated Capital Management, an institutional research and asset management firm, is distributed for informational and educational purposes only and is not intended to constitute legal, tax, accounting or investment advice. Opinions, estimates, forecasts, and statements of financial market trends that are based on current market conditions constitute our judgment and are subject to change without notice. Integrated Capital Management does not have any obligation to provide revised opinions in the event of changed circumstances. We believe the information provided here is reliable but should not be assumed to be accurate or complete. References to specific securities, asset classes and financial markets are for illustrative purposes only and do not constitute a solicitation, offer or recommendation to purchase or sell a security. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investment strategies and investments involve risk of loss and nothing within this report should be construed as a guarantee of any specific outcome or profit. Investors should make their own investment decisions based on their specific investment objectives and financial circumstances and are encouraged to seek professional advice before making any decisions. Index performance does not reflect the deduction of any fees and expenses, and if deducted, performance would be reduced. Indexes are unmanaged and investors are not able to invest directly into any index. The S&P 500 Index is a market index generally considered representative of the stock market as a whole. The index focuses on the large-cap segment of the U.S. equities market.