By Frank Holmes, CEO and chief investment officer for U.S. Global Investors

When Colorado-based Molycorp Inc. filed for bankruptcy in 2015, the U.S. lost its sole remaining miner and producer of rare earth elements (REEs) —those inconspicuous metals with unpronounceable names like praseodymium, yttrium, and gadolinium.

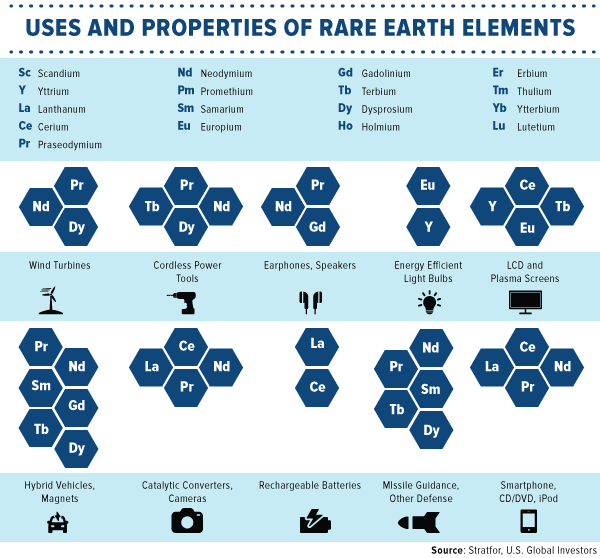

The company’s key project, the open-pit Mountain Pass mine in California, was once the world’s top source for rare earths, which are used today in a growing number of important high-tech applications, from lasers to wind turbines to missile guidance systems.

Multinationals, as varied as Boeing, Honeywell, Sherwin-Williams, Bayer, ExxonMobil, Stanley Black & Decker and Qualcomm all, have financial interests in the availability of REEs. The iPhone in your pocket would be inoperable without 16 of the 17 rare earth metals. Each F-35 fighter jet is estimated to contain about half a ton of the elements. To improve motor efficiency, Tesla’s 2019 Model S and Model X are installed with a permanent magnet motor that uses rare earth neodymium-iron-boron magnets.

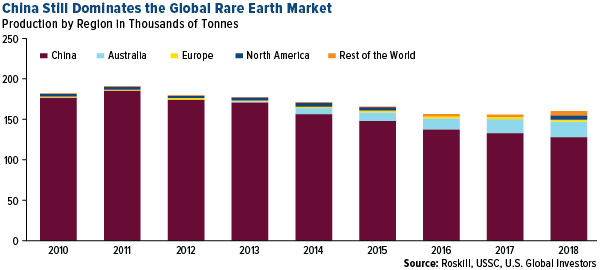

Lacking its own domestic supplier, the U.S. has for years been dependent on China, the world’s biggest producer by a huge margin. The Asian country has enjoyed a near-monopoly in the rare earth market, representing between 80 percent and 90 percent of global output.

Cracks in that market dominance are beginning to appear, however, as Australia has recently emerged as a competitive supplier. From 2013 to 2018, Australia’s annual output of REEs exploded more than 1,600 percent, from around 1,000 tonnes to 19,000 tonnes, according to consultancy firm Roskill.

The largest Australian company involved in the mining and processing of REEs is Lynas Corp., which trades on the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX). Other rare earth mining companies trade there as well, including Northern Minerals Ltd., Arafura Resources Ltd., and Alkane Resources Ltd., but Lynas is the biggest player by far, not just in Australia but in the entire world outside of China. It controls the prolific Mt. Weld deposit in Western Australia, which is responsible for about 8 percent of world output. Once ore is extracted, the company processes it in Malaysia at the Lynas Advanced Materials Plant.

I’ll have more to say on Lynas in a moment.

Seeking to Diversify Away From China

As I discussed back in May, China’s dominance poses a considerable economic and national security risk to the U.S., one that’s become all the more apparent in the months since trade relations between Beijing and Washington turned sour. “Control of the rare earth supply gives Beijing both economic and military advantages over the U.S.,” writes Michael Silver, CEO of American Elements, in a Wall Street Journal op-ed.

The word “weaponized” is overused today, but that’s precisely what Chinese officials have done with respect to these vital elements, threatening to curb their export to the U.S. in retaliation over tariffs.

As if to validate these not-so-veiled threats, China’s rare earth exports to the U.S. have begun to slow. In September, they fell nearly 18 percent from the previous month.

There’s a precedent of China using REEs as geopolitical leverage. In 2010, Beijing blocked its export to Japan in a dispute over the detention of a Chinese fishing captain. The move ultimately failed, as it had the effect of forcing Japan to build up its own rare earth supply chain. The Japanese government, in fact, helped fund the development of Lynas. Just last year, Japanese researchers discovered what’s been described as a “semi-infinite” deposit of rare earth metals underneath the country’s waters.

Faced with a similar predicament, the U.S. government and American corporations have been considering ways to limit their reliance on foreign supply. In December 2017, President Donald Trump issued an executive order calling on government agencies to explore strategies to “reduce the Nation’s reliance on critical materials.” Among the strategies—locating domestic deposits, improving access to data and expediting mining permits.