Vltava Fund commentary for the third quarter ended September 30, 2018; titled, “How We Determine The Value Of Our Stocks (And Of The Entire Portfolio)”

Several years ago, we began showing a graph with two curves during our presentations at annual shareholder meetings and in the autumn seminars. One curve shows the change in Vltava Fund’s NAV and the other the development of the value of the Fund’s entire portfolio as we estimate it continuously over time at weekly intervals. We have been publishing this graph twice a year, and in the meantime your requests for more up-to-date value developments were increasing. This past July, we therefore decided to begin providing current estimates of the portfolio’s value in the fact sheet you receive from us every month, right next to the current NAV. You thus will be able continuously to picture the difference between NAV and the portfolio’s value, in other words, how inexpensive are the shares you hold through the Fund, and also what this all means concerning probable future returns. This is a rather fundamental step, and that is why I want now to discuss what this portfolio value actually is, how it is estimated, and why it is important.

A Company’s Value

We believe the only logical way to invest is to pay a price that is lower than the value that we get in return. This rule should be universal and should apply for all types of investments, not just equities. Price and value are two different categories. Price is usually clear. In the case of equities, one has only to look at the current price on the stock exchange. That is determined by the momentary levels of supply and demand for the given stocks, and is the same for everybody. It is more difficult with value. Theoretically, the value of each asset is equal to the present value of all cash flows that the asset’s holder will receive in the future.

It is not quite so easy, however, to apply this simple definition in practice. Among other things, one has to estimate the company’s free cash flows into the future. That future is very long for stocks, because stocks theoretically have a lifetime that is infinite. That means more than half the value of the vast majority of the analysed companies derives from cash flows more than seven years into the future. Anyone who has ever managed a company knows that such long projections are highly unreliable and often are more indicative of the analyst’s subjective opinions than of the company actually being analysed.

The fact that something is difficult, however, does not mean that it is impossible. In analysing individual companies and determining their value, we proceed from two basic conditions: Analysing a company makes sense only if, first, what we are trying to determine in that analysis is actually determinable and, second, if it is at the same time sufficiently important. In establishing the values of companies, we therefore avoid those for which estimating their values takes on a semblance of gazing into a crystal ball. This includes companies which are non-transparent, unstable, financially weak, too young, or with unpredictable management, but also those for which determining their value requires looking into a too-distant future. We are aware that our estimate of the value of such a company would be very unreliable and therefore practically worthless.

Instead, we endeavour to focus on companies that are well-established, stable, transparent, financially strong, having consistent management, and that already produce very strong free cash flows, as those cash flows give us something upon which our analysis can be based. Even though they still contain a substantial dose of subjectivity, the estimates of such companies’ values can be utilised in putting together a portfolio.

The objective of the entire analytical process is not to establish a company’s value with exacting precision. That is impossible, and it is not even important. What is important is that we become convinced that the company’s value is substantially greater than is its price. For this purpose, we do not need to establish a precise value. We just need to estimate a range within which the company’s value probably lies. Its lower limit represents our conservative estimate. If this is substantially higher than the share price, then that information is sufficient.

Development of Value and Risk

A company’s value is not static, but rather it changes over time. It increases over the long term for equities as a whole, and this explains why share prices also grow substantially over the long term. This is because (whether we speak of individual stocks or the market as a whole) stock value draws the share price or prices towards it over the long term. But there are great differences among individual stocks. Value increases for some, diminishes for others, and stays about unchanged for still others. For some stocks, it changes slowly, and for others it leaps up dramatically. Compare, for example, the long-term price developments for JP Morgan and Deutsche Bank, Berkshire Hathaway and Immofinanz, or Apple and Nokia. The developments of these companies’ values eventually exerted a pull on their prices, and the differences are dramatic. If there is one thing a person can rely upon in equity markets it is the fact that price follows the development of a company’s value over the long term. Sometimes it takes a very long time for this to happen, but it always happens eventually. The selection of stocks matters really a lot, however. When picking stocks, we are interested not only in what is a company’s value today, but most of all where it will go in the future.

The growth in value is very important. If the current difference between price and value is large but value is increasing only very slowly, then in our investing we have to rely on the difference between price and value narrowing very quickly. We sometimes enter into such investments, but we like much more those where the difference between price and value is large and at the same time value is increasing rapidly. Then we can say that time is on our side and we just have to hold and wait. Best of all are those investments where value is growing rapidly but we need not pay much for that growth, when the share price is at such a level that we receive the future growth practically for free. There is usually very low risk associated with such investments, because we are not dependent on the future’s developing in accordance with how we envision it.

What does this all look like in practice for us?

The crux of our work lies in studying one company after the other. In the more than 14 years of the Vltava Fund’s existence, we have studied 1904 such companies from 64 countries. We then remove those we do not understand, those whose business we do not like, and those for which the value estimate is highly unreliable. Most companies fall into one or more of these categories. In the majority of cases there is no need to come back to these, because an unattractive business usually will remain unattractive. There still remains a sufficient number of companies regarding which we feel we understand what they do, whose businesses we like, and whose value can somehow be estimated. Such companies we study continuously year to year. There are many companies about which we have a history going back more than a decade, and even 25 years for some. The outcome of all this analytical activity is a list of good companies with a value estimate for each. We then select stocks for our portfolio from this list. Because we are not the only investors seeking good companies, the prices of these stocks are mostly at or above our estimated values. With a little self-discipline and patience, however, we can wait until we see a share price move substantially below its value – and that is the signal to buy.

We use various valuation models for different types of companies. These are not in and of themselves very complicated, but they are supported by rather extensive analysis of the given companies, their entire sectors, and their competitor companies. It would make this letter to shareholders unbearably long to describe specific valuation methods, so I will not do so here. We are planning to focus on them during our October seminar. So let’s skip over this step here and look at one concrete result of our analyses.

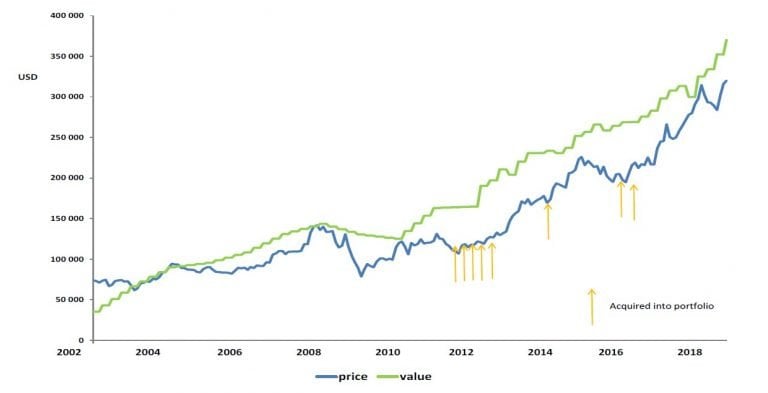

In the following graph, you can see the development of the Berkshire Hathaway share price and the development of our estimate of the share’s value, as well as points in time at which we bought it.

Development of value and price, Berkshire Hathaway, BRK-A (2002–2018)

Berkshire Hathaway has been our largest position for a long time and also is one of our oldest. Several conclusions can be made from examining the graph:

- The stock’s value is increasing over the long term, even though the long-term growth is interspersed with shorter periods of stagnation or decline.

- Share price follows the development of value over the long term.

- The development of price is much more volatile than is the development of value. A temporary drop in price by 40% would in no way be exceptional.

- From a long-term perspective, the price volatility loses some of its importance, but this is a source of buying opportunities when the spread between price and value widens to more than usual.

This is the key idea of our investment philosophy: The main long-term objective we monitor in selecting stocks is the growth in their value and growth in the value of the portfolio as a whole. Most of the time we ignore movements in share prices, but at times when they diverge extremely from the value we can utilise them for buying or selling.