The bull market that began in 2009 reached seven years of age on March 9.

Despite the market’s impressive gains, recently many valuation conscious investors have been voicing doubts about the classic Graham-Dodd value-based investment style.

In accordance with the basic principles of value investing, investors’ believe that buying companies that are cheaper according to various balance sheet metrics should provide excess returns over time.

However, in the past few years the dreaded value trap (buying a company that is cheap only to see that company get cheaper – for good reason) has plagued value-oriented ETFs and mutual funds. The market decided that many apparently attractively valued companies were in fact overvalued, as their assets and earnings were overstated and unsustainable.

The energy, financials, and materials sectors, all sector overweights in value-oriented ETFs, have been hardest hit. The worst price damage has been done to emerging markets, and valuations in the space again are appealing – at first glance. In this article we will examine the opportunities and risks involved with investing using the value factor, particularly in emerging markets.

Screening for investment ideas based on comparative valuations is an idea that intuitively makes sense.

Indeed, the value factor was the first factor identified by academic finance, in Fama and French’s seminal 1992 article “The Cross-Section of Expected Stock Returns,” every factor has it weaknesses, however, and value investing’s risks, in particular, have recently been exposed.

While cheap comparative valuations might signal an investing opportunity, low valuations can also be a signal of the risks a company might face, including: higher financial leverage and stress (and thus higher risk of failure), negative market sentiment and technicals, and current business weakness.

As the numbers below bear out (for the five years ended February 2, 2026), value investing has not delivered many benefits:

In the U.S., the value factor has dramatically underperformed in the same five year period, producing lower returns at a higher volatility than the broad MSCI USA Index, while the momentum and volatility factors have produced comparatively strong returns, particularly per unit of risk. The factor also has fared poorly in emerging markets, producing returns that were lower than the broad Emerging Markets Index at a volatility of nearly 20% per year.

The recent poor returns of value investing help frame the dilemma facing investors in emerging markets, where valuations appear compelling but have been that way for some time. The cheaper valuations in emerging markets have indicated weakness and stress rather than strength, and returns have been very poor with above average volatility. Nevertheless, the case for emerging markets is not hard to make. Let’s start with valuations, where emerging markets stand out globally.

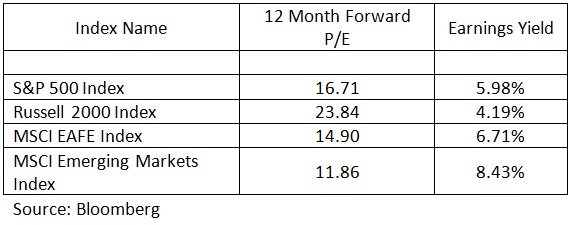

Here are valuations using 12- month forward P/Es as of March 9:

U.S. (P/E of 16.7) and particularly U.S. small cap (P/E of 23.8) valuations appear quite rich, while emerging markets, with a P/E of just 11.9, appear cheap. One way we like to think about valuations is to take their reciprocal, the earnings yield, and use it as a rough estimate of 10-plus year forward returns.

The concept was popularized by Robert Shiller and his work with the CAPE (Cyclically Adjusted P/E Ratio). While the P/Es that we show here are not cyclically adjusted, at least for emerging markets, we can at least state that given the collapse in commodities and emerging market currencies, we believe these earnings are not at a cyclical peak – something we cannot generally say about U.S. valuations.

When doing this, emerging markets again look attractive, with an earnings yield of over 8.4%.