When we initiated our forecast on the S&P Healthcare Claims Indices in 2014, we wanted to avoid the effects of the ACA on individual and Small Group claim costs, so we focused on Large Group and Administrative Services Only (ASO) trends. The individual claim costs continued to show a sharp divergence in trends from the group business claim costs through 2014. In the first quarter of 2015, the high cost trends for individual were still below 2014 levels, as predicted. Also as predicted, the Small Group trends have begun to show an uptick (from virtually flat in December 2014 and January 2015 to nearly 7% by April 2015 on a three-month basis), but this increase was not nearly as strong as the increase for individual during the same period.

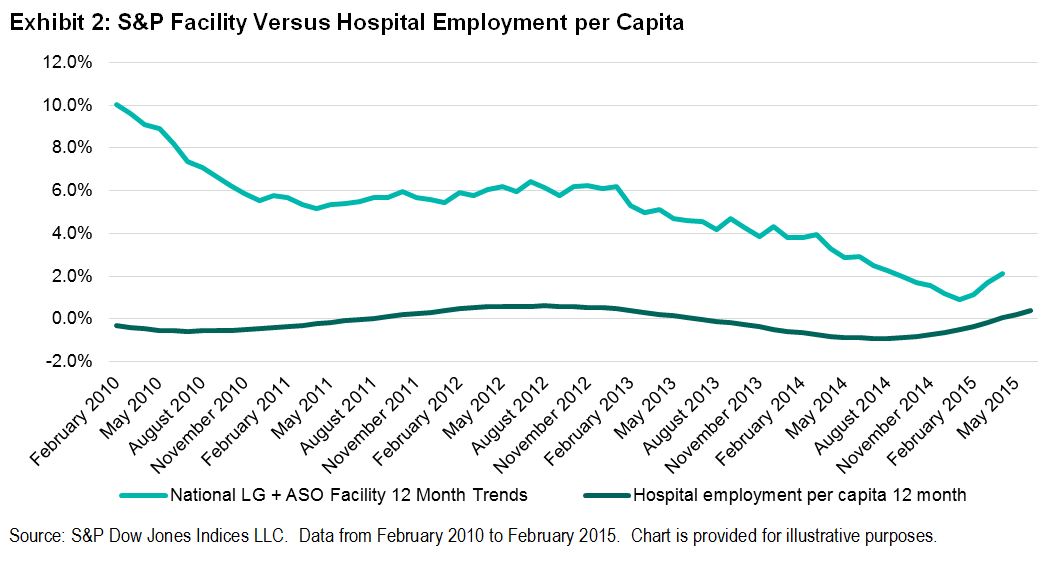

We expect that there could be a further increase in 2015 Small Group trends as a result of the ACA changes. The capacity of hospitals, as measured by employment per capita, declined below long-term average levels, but since late 2014, employment has increased at a faster pace. Medicare initiatives to cut readmissions and increase observation (emergency room) holds in order to avoid unnecessary admissions have been affecting Medicare and non-Medicare hospital patients by reducing admissions.[1] [2] These may have run their course.

[1] Due to the effects of deductible and copay leverage, large employers’ benefit plans that have not changed rates in the previous year could increase by as much as 2.5% or more on bronze-level plans and by 1% or more on gold-level plans. Risk takers may need to take this into account. In addition, the S&P Healthcare Claims Indices do not reflect the impact of benefit buydowns by employers (i.e., higher deductibles, etc.), since the indices are based on full allowed charges. Actual trends experienced by employers and insurers in the absence of benefit buydowns can be expected to be higher than trends reported by the S&P Healthcare Claims Indices due to plan design issues such as deductibles, copays, out-of-pocket maximums, etc. Benefit buydowns do not represent trend changes, since they are benefit reductions in exchange for premium concessions, but they can have a dampening effect on utilization due to higher member copayments. This can have a dampening effect on trends measured by the S&P Healthcare Claims Indices compared with plans with no benefit changes, further pushing up experienced trends relative to those reported in the indices. The long time lag between real personal income growth (highly correlated with real GDP) and the impact on healthcare trends defer the impact on healthcare costs for 30 to 36 months, and that is reflected in our forecasts. The lag on inflation is much shorter, with a range of 12 to 18 months.

[2] Readmission rates are much higher for the Medicare population than commercial patients, and Medicare has seen significant admission rate reductions in recent years. Medicare 30-day readmission rates have dropped from an average of 19.0%-19.5% four-to-seven years ago to under 18% in early 2014.

[3] Our operative theory is that healthcare is primarily a supply-driven system due to consumers being immunized from significant cost because of the effect of insurance. This increases the demand above what it might otherwise have been in the absence of insurance. Although ongoing market increases in deductibles and co-pays have a downward effect on demand, this would only have a marginal impact relative to the effect of having no coverage at all. This was demonstrated in the Rand Health Insurance Experiment conducted from 1971 to 1986.