Passive portfolio managers (PMs) sometimes get a bad rap. They’re only tracking an index after all, not trying to beat it. How hard can it be? Well, it turns out that, despite what seems like a simple proposition, there is, in reality, an awful lot of detail, technical expertise, and value add. We won’t go into every aspect of it in this blog, but there are numerous key issues, be it; scrutinizing every cent of a fund’s costs, reinvesting dividends, managing cash, rolling hedges, dealing with corporate actions, adjusting positions at rebalances, and, particularly for fixed income PMs, optimizing fund holdings.

But, if the ultimate goal remains providing an investor with an experience that mirrors the underlying index as closely as possible, how can we tell how well the PM is doing? Well, it turns out that there are two key numbers, similar, but subtly different, that can do a pretty good job of answering this – tracking error (TE), and tracking difference (TD).

So what are these two numbers that keep our PMs to account, and how should we interpret them? Well, tracking difference (TD) is certainly the more straight-forward of the two. It is simply the difference between an index return, and a fund return, over a given period. So, if the index you wanted exposure to is up 10% in a year, and the fund returns 9.8%, then the tracking difference is clearly -0.20%, or 20 basis points. There are many components of TD, and we won’t go into them all here, but, the biggest driver is likely to be the fee that the fund charges. After all, absent any other differences, the fund will at least underperform the index by the size of the fee (and this is generally charged to the net asset value (NAV) evenly across the year, so, after six months, you’d expect to see a TD of at least half the expense ratio).

One caveat though. It is probably best to compare TDs only between funds that track similar indexes. After all, a passive PM will almost always have a harder time buying and holding the assets of a more esoteric market. So to compare the TDs of a large-cap U.S. equity fund with, say, a small-cap emerging market fund would be to ignore the inherently large transaction costs that the latter strategy will be more likely to incur.

The more complex cousin of TD is TE. This metric takes the standard deviation of the difference in returns between a benchmark and a portfolio (or, equivalently, an index and a fund in the case of a passive vehicle). So effectively, it’s a volatility number (generally expressed in annual terms). As such it can be interpreted in the same way that a normal volatility can – by providing a probabilistic range of excess returns. For example, a fund that has a TE of 0.15%, and a TD of -0.20%, should normally be expected to have an excess return of between -0.50% and +0.10% versus the index, 95% of the time (this is a classic plus and minus two standard deviations). We actually find this way of looking at the world incredibly useful because it incorporates both numbers, and might enable funds offering similar exposures to be more meaningfully compared. We plan to write more on this in due course.

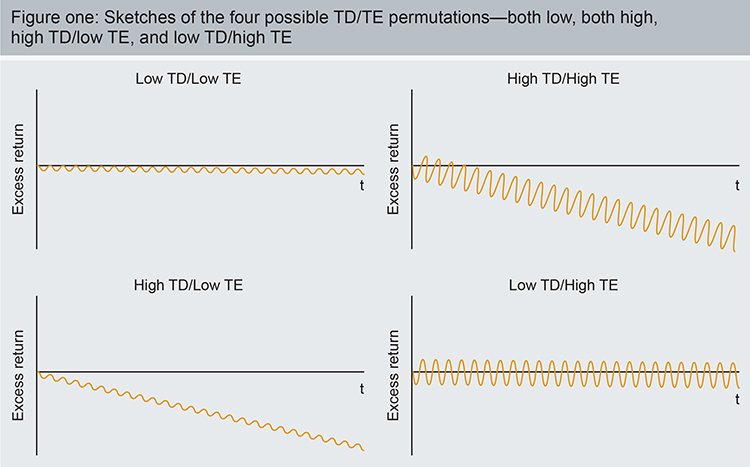

One final thought on TD and TE, that helps to emphasize the importance of looking at both, is illustrated by the below four sketches. In our view:

- The low TD and low TE scenario is clearly dominant. We can see no argument not to prefer funds which, all other things equal, exhibit low TDs and low TEs.

- Similarly, we feel the high TD and high TE example is demonstrably the worst.

- However, we think the two “mixed” examples of high TD and low TE, and low TD and high TE, are intriguing – because it’s not obvious which one an investor should prefer. Our initial thinking is that a short term investor might care more about low TE given that it offers a better chance of coming in and out of a fund at a level that is closer to the index. On the other hand, a long term investor might care less about that aspect, and instead prefer to have a low TD eating away less of their net asset value (NAV) in the long run. If they’re not planning to trade in and out of the fund, presumably they might be more accepting of a high TE.

The bottom line is that both TD and TE matter, and investors should look very carefully at both if they want to get their investments on track.

![]()