By Peritus Asset Management

Accurately calling interest rate moves has proved to be a difficult, and futile, task for investors over the past several years as we have seen wild moves and really no sustained direction. As we entered 2014, virtually everyone (except ourselves) expected rates to rise as the long awaited “taper” began. Yet, the opposite played out. After seeing the 10-year Treasury yield hit the 3% level in late 2013 and early 2014, we have seen it vacillate between the 1.5-2.6% range over the past several years.(*1)

![]()

While the only aspect of rates that can be accurately predicted seems to be volatility, many are left wondering if the swift move in rates that we have seen in the first two months of 2018 is the beginning of a sustained move upward. As we look forward, we know the Fed has stated their intention to raise the Federal Funds Rate at least another three times this year, but just what does that mean for Treasury yields? We have seen the Fed undertake a number of rate increases already, all while the 10-year Treasury yield is at the same level it was four years ago. With the relative (lower) sovereign rates around the world and demographic overhangs (aging global population), we are not convinced that a massive rise in rates is on the horizon. So far this year we have already seen the 10-year rise nearly 50bps (*2) , so while we may hit and even surpass 3% on the 10-year, we feel the bulk of the move is already behind us.

However, for the sake of argument, let’s assume that rates do rise materially from here. What does that mean for the high yield market and the various “strategies” out there to deal with rising rates? High Yield in a Rising Rate Environment First let’s look at the high yield market and how it has traditionally responded to rate moves. Historically speaking, the high yield bond market has performed well in a rising rate environment, as we discuss below. Higher coupons and yields in the high yield space help cushion the impact of rising interest rates. High yield bonds have the highest coupons/yields in corporate fixed income. The following chart depicts the current yield-to-worst, coupon, and the spread over Treasuries for several fixed income asset classes.(*3)

Let’s think about this intuitively for a minute. If you own a bond with a yield of 3% and interest rates move up 1% that would obviously have a meaningful impact, as we are talking about a move equivalent to 33% of your total yield. However, if you instead have a starting yield of 7.0% on a bond and interest rates move that same 1%, you are looking at significantly less impact, at about a 14% change in yield. So the higher the starting yield, typically then the less interest rate sensitivity.

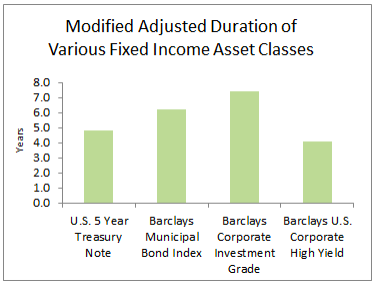

High yield bonds have shorter durations than other asset classes in the fixed income space. Duration is a measure of sensitivity to changes in interest rates that incorporates the coupon, maturity date, and call features of a bond. The fact that high yield bonds are typically issued with five to ten year maturities and are generally callable after the first few years, as well as offer higher coupons, typically provides the high yield sector with a shorter duration, thus less interest rate sensitivity, versus other fixed income asset classes. We’ve profiled some duration comparisons to the right: (*4)

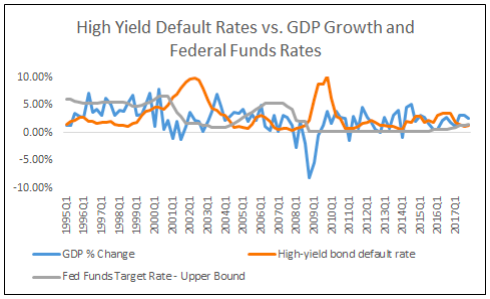

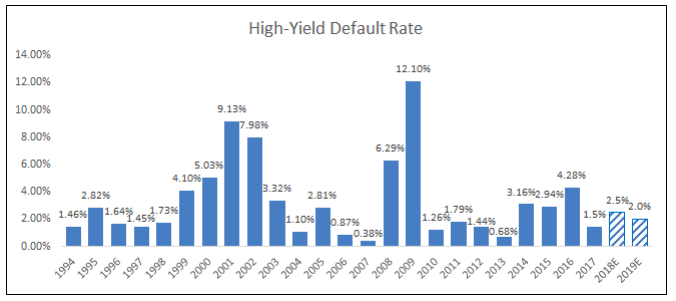

The prices of high yield bonds have historically been much more linked to credit quality than to interest rates. Historically, interest rates increase alongside a strengthening economy and a strong economy is generally favorable for corporate credit and equities alike. Due to the nature of the high yield bond market, the major risk on the minds of investors tends to be default risk (not interest rate risk), causing them to be much more concerned with the company’s fundamentals and credit quality than interest rates. When the economy is expanding, profitability, financial strength, and credit metrics generally improve. The move higher in Treasury yields that we have seen during the first couple of months of 2018 has been tied to expectations that the improved economic growth will give the Fed the fuel they need to continue with rate increases. As we look at the history of the high yield market, we have seen a negative correlation between the Federal Funds Rate and high yield bond default rates, which makes sense—if the economy is improving, the Fed is increasing rates, and simultaneously default rates are falling due to the stronger economy. On the flip side, if the economy is weakening, we generally see the Fed easing and default rates often increasing. The chart below demonstrates this historical relationship.(*5)

High yield default rates have been below historical averages over the past several years, with the exception of 2016 when we saw default rates temporarily increase due to the collapse in energy and other commodity prices. As we look forward, we are generally seeing stable fundamentals for high yield issuers and the expectation is for default rates to remain low.(*6)

A stronger economy would undoubtedly be a positive from a credit perspective and would likely indicate lower default rates, meaning likely improved prospects for the high yield market.

High yield bond returns are negatively correlated with Treasury returns. This means that as Treasury yields (interest rates) increase and prices decline, and thus returns decline, high yield would theoretically experience the opposite change with a positive return. Additionally, while high yield is still positively correlated to investment grade, we see a stronger, positive correlation between investment grade and Treasuries. As noted above, over the past 25 years, high-yield bonds exhibit negative correlations to the 5-year and 10-year Treasury bond of -0.12 and -0.10, respectively, versus a far higher positive correlation of +0.61 and +0.67, respectively, for high-grade bonds.(*7)

![]()

Not only does the negative correlation between high yield bonds and Treasuries indicate that high yield bond returns have historically performed positively in the face of rising Treasury yields, given these lower or negative correlations versus other asset classes, especially the more interest rate sensitive asset classes such as investment grade, an allocation to high yield bonds may help improve portfolio diversification and potentially lower risk depending on the mix of assets. On the flip side, an allocation to investment grade not only provides you a much lower starting yield, but can result in significantly more interest rate sensitivity.

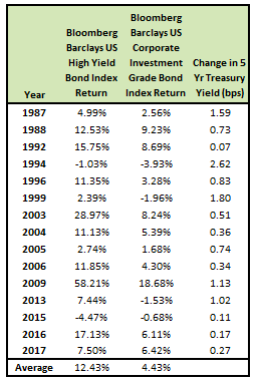

Historical Performance When Rates Rise Those are theories, but let’s look at some hard data as to how high yield bonds have actually performed in a rising rate environment. In the over 30 years of data, since 1986, Treasury yields have increased (i.e., interest rates rose), in 15 of those years. In all but one of those 15 years, high yield has outperformed the investment grade bond market. The long-term numbers show that over those 15 years when we have seen Treasury yields/interest rates increases, high yield had an average annual return of 12.4% (or 9.2% if you exclude the massive performance in 2009). This compares to only a 4.4% average annual return (or 3.4% excluding 2009) for investment grade bonds over the same period.(*8)

So the data is clear that the high yield bond market has historically not only provided investors with solid returns during years in which we see interest rates increase, but has also dramatically out performed its investment grade counterpart. Looking at this is a different way, below we lay out the historical returns for the high yield index during periods of rising rates. Here we specifically look at how the index performed prior to and following periods when rates rose 30bps, 50bps, 70bps, and 100bps over certain periods of time.(*9)