By Heather Rupp, Peritus Asset Management

Investing in floating rate bank loans has been a popular strategy this year given investor concern about higher rates. We have seen positive fund flows into floating rate loan mutual and exchange traded funds (ETFs) in 15 of the last 16 weeks, and so far this year $8.1 billion of inflows to loan mutual and exchange traded funds.(1)

At face value this seems like a “no brainer” trade, and many have embraced it as such, but the actual numbers tell a bit of a different story. For instance, 2013 was the last annual period in which we saw a meaningful increase in US Treasury rates, and during this period a whopping $63bn flowed into floating rate loan mutual and exchange traded funds.(2) However, in 2013 floating rate loans returned 5.3% versus 8.2% for high yield bonds.(3)

So even with the 10-year Treasury yield increasing by over 1.2% and the 5- year Treasury increasing over 1.0% (both over 50% from their respective yields at the beginning of year) (4) and a massive amount of inflows into the loan space in 2013, the high yield bond market, helped by higher initial starting yields, still outperformed the loan market, despite the fact that the high yield bond market saw slightly negative net outflows for the year.(5)

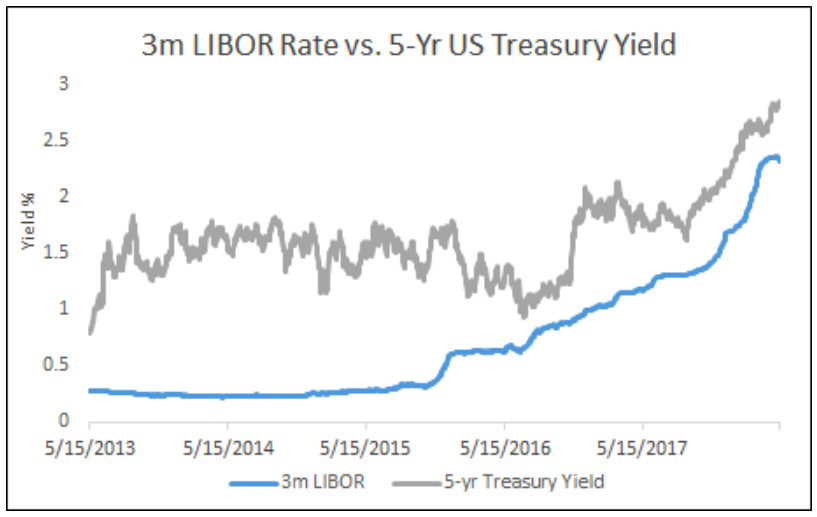

Another consideration when investing in the loan market must be an understanding of what the “floating” rate is tied to. Bank loans are generally based on short-term LIBOR rates, which doesn’t necessarily tie closely to longer term 5- and 10-year Treasury rates, which are the more relevant rates for high yield bond investors.

Related: The LIBOR Spike and Why It Matters

For instance all through 2013-2015 LIBOR was virtually flat, while Treasury rates surged. Then in 2016, we saw LIBOR increasing while Treasuries fell. It has only been over the last year and a half that LIBOR and the 5-year have been both moving upward.(6)

The relevant interest rate is important but so is understanding how the actual spread over that base rate works. Loans differ from bonds in that bonds are generally issued with a non-call period covering the first several years after issuance, and then have a set call schedule indicating premium prices at which the company can redeem the bonds over subsequent years.

Depending on the term of the bond, this often provides the investor call protection for much of the term of the security. However, with floating rate loans, that call protection period is generally a much shorter period of time. With a newly issued loan, you may have a non-call period for the first six months to a year or two, but many loans are issued with no call protection. Given the supply and demand imbalance in favor of issuers of late, there is often no call protection for loan investors at all.

Related: ETF Trends Fixed Income Channel

Why does this matter? Because the very minimal call protections can lead to constant “re-pricing” activity. This means that the issuer approaches the investor to lower the interest rate on the loan. The loan remains outstanding but now the investor is faced with a lower rate. So while investors have to approve the repricing, in times of high demand, it isn’t hard for issuers to get the repricing activity through (as the alternative is that they call the loan altogether and the investor loses the holding).

Over the past couple years we have seen a huge wave of repricings. In 2017, 45% of the $974bn in gross new issuance volume was related to repricings and so far in 2018, 48% of the $304bn in gross new issuance is related to repricings.(7) Index-based/passive bank loan funds track a specified index and thus largely hold the securities in that index. When a security is repriced and remains outstanding and part of the index, then these funds would be subject to a lower total coupon rate on that security.

In a period such as we are seeing now, interest rates can be rising via the LIBOR increase, so the base rate on the loan is increasing, but with the repricings that spread over the base rate can be falling, meaning the actual total coupon rate the investor receives may be actually falling, or at least going up much less than the LIBOR move would indicate.

An additional note, the general perception seems to be that loans are always less risky than bonds. In many cases we do see a bifurcated capital structure, whereby the company has a portion of their capital structure in a floating rate loan and revolver, which is senior in the capital structure and secured, and then the remaining portion of the debt issued is in subordinated bonds.