Japanese unemployment has fallen below 3% and companies face significant upward pressure on wages for part-time employees. Employers can avoid offering significant pay increases to their part-time workforce by instead offering them fulltime employment status. Fulltime workers in Japan have far higher social status and workers are willing to accept increased “face” in place of a fatter paycheck.

Despite helping hold down wage gains, this move to fulltime employment significantly contributes to increased economic dynamism and growth. Japanese part-time workers tend to save as if they could be fired at any time, even after years of consistent contract employment. Part-time workers often defer marriage and major expenditures like buying a house or a car until they achieve fulltime status. Moving more workers to fulltime status tends to mute overall wage gains, but also unleashes more consumption and less savings from these Japanese workers, in our view.

Better Economy Translates into Better Corporate Earnings

Abe’s successful reform of corporate governance in Japan is helping turn the increased buying power and confidence of the Japanese consumer into much stronger corporate earnings and much improved return prospects, in our view. Investors have been told so often and for so long that debt and demographics explain the long bear market in Japanese equities that it is now accepted as true.

We believe that Japanese equities struggled for nearly 20 years because the interconnected nature of Japanese companies (Mitsubishi Steel owning Mitsubishi Life owning Mitsubishi Automotive owning Mitsubishi Steel) prevented a rational popping of the Japanese equity bubble, and simultaneously depressed profitability as clubby, interlocking boards valued stability over profitability. ![]()

The US equity bubble of 1999/2000 peaked at about 35x earnings and once the bubble popped it only took about 18 months to return valuations to a more normal 22x. By contrast, the Japanese “keiretsu” system of interconnected company ownership helped inflate a much bigger bubble and prevented a rational popping of that equity bubble. The Japanese equity bubble peaked at 70x earnings in 1990 and did not drop below 22x earnings until 18 years later during the 2008 financial crises.

Abe has built upon earlier reforms to largely disassemble the interconnected keiretsu companies, and Japanese equities trade at market determined prices that are now typically less than 14x earnings. Profitability has similarly improved thanks to Abe’s insistence upon return on equity (ROE) targets for all publicly traded companies.

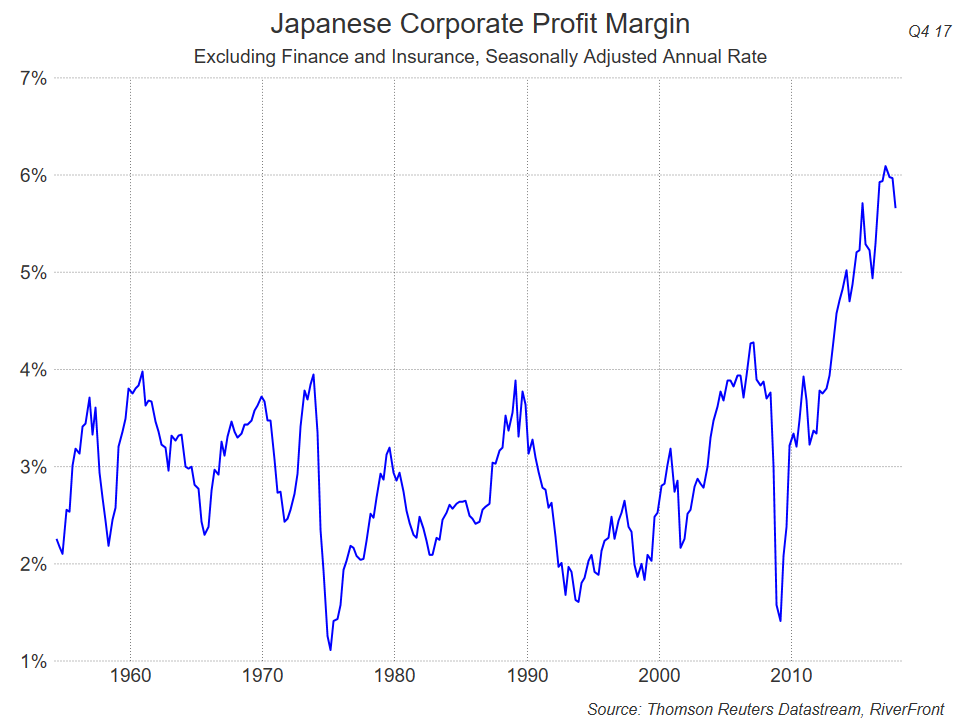

Achieving these targets is now a matter of “face” in Japan, and if a competitor raises its ROE target then every company in that industry faces social pressure to match or exceed the new, higher benchmark. During the 1980s heyday of “Japan, Inc.” when Sony, Panasonic and Honda were the most valuable brands in the world, profit margins in the clubby, interconnected world of corporate Japan never exceeded about 4%. Thanks to Abe’s sweeping corporate governance reforms, Japanese non-financial profit margins are approaching 6% and rising fast.

Conclusion

We believe that some of the best investment opportunities are created when a long-established market theme is beginning to change. After a 28-year bear market, investors may be understandably reluctant to change their attitude toward Japanese equity investments. Our recent visit to Japan reinforces our longstanding view that Abenomics represents a new chapter for Japanese investors.

We can see the tangible benefits of increased household income and employment stability, and improved corporate governance is translating these economic improvements into the best profit margins Japanese companies have produced since World War II. Investors who do not recognize Japan’s significant achievements over the past 5 years may miss one of the best investment opportunities in the global marketplace, in our view.