By Gary Stringer, Kim Escue and Chad Keller, Stringer Asset Management

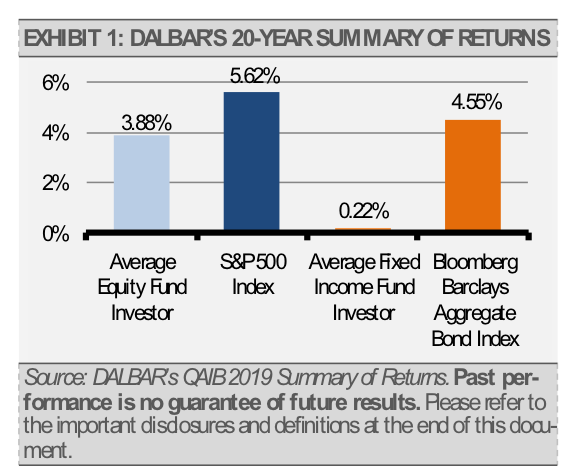

Coaching is one of the greatest values that Financial Advisors bring to their relationships with clients. We live in an emotional world, especially when it comes to the financial markets. At Stringer Asset Management, we believe that errors resulting from emotional decision making when investing is the primary reason that many investors do not capture the potential rewards that financial markets can provide. Coaching based on precepts of behavioral economics can benefit investors and strengthen their relationships with their Financial Advisors.

Richard Thaler won the 2017 Nobel Prize in Economics for his contributions to the field of behavioral economics. Despite the historical economic assumption that people make rational decisions, behavioral economics shows that people often make decisions that may not be rational. The work of Thaler and many others in behavioral finance may be boiled down to practical techniques that we think can help investors achieve better results.

PRACTICAL STEPS TO IMPROVE RESULTS

STEP 1: BE HUMBLE, WE ARE ONLY HUMAN

Investors cannot fight human nature, but steps can be taken to keep detrimental behavior in check. The first step is for investors to admit they are fallible. Once investors acknowledge that they do not know what is going to happen for certain, processes can be put in place to help control the behavioral pitfalls of investing.

STEP 2: HAVE A WELL THOUGHT OUT & DOCUMENTED PLAN

To avoid distractions investors should focus on the big picture, which starts with a fundamentally sound investment strategy. Without a definable and repeatable process, a positive outcome is just dumb luck. In his 1999 commencement address to the University of Pennsylvania, Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin outlined his four principles to decision making: “First, the only certainty is that there is no certainty. Second, every decision, as a consequence, is a matter of weighing probabilities. Third, despite uncertainty we must decide and we must act. And lastly, we need to judge decisions not only on the results, but on how they were made.1”

STEP 3: INCLUDE RELIEF VALVES

Every investment strategy needs relief valves to help keep the negative impact from human behavior from causing harm. We see an analogy in engineering. For example, a mid-mission oxygen tank rupture caused the Apollo 13 space craft to abort its mission before landing on the moon. Helping avert disaster was a relief valve built into the tank which mitigated the damage and allowed the crew to make it safely back.

Investors can also build relief valves into their portfolios to avert disaster and help them sleep at night. For example, investors should keep savings and emergency funds separate from investment funds. Savings and emergency funds are safe funds (i.e., cash). Investment funds are where risk should be taken, and the amount of risk depends on the investor’s goals, objectives and constraints.

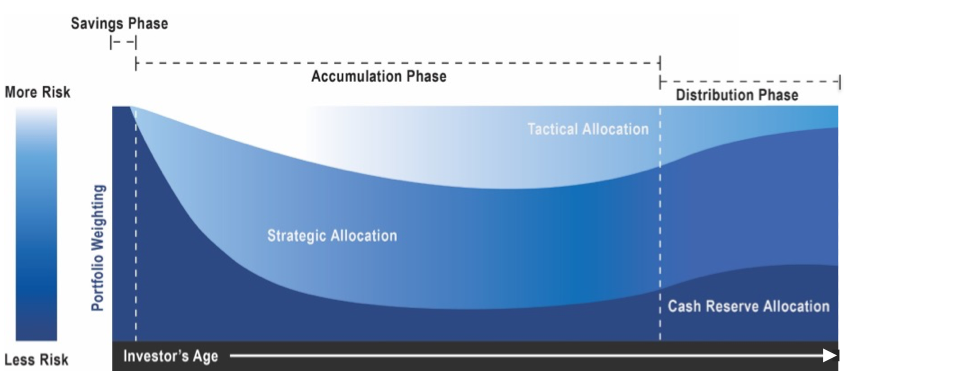

Consider the investor lifecycle chart below as an example of a sound investment plan. The investor starts off just out of school and their immediate goal is to build a cash reserve to cover emergencies. Once this reserve is built, the investor can begin the accumulation phase by allocating to both strategic portfolios (relatively static portfolios based on long-term expected return characteristics) and tactical portfolios (more active portfolios that attempt to take advantage of perceived market imbalances that create attractive short-term investment opportunities).

Throughout the life cycle, the cash reserve and tactical allocation can be considered the relief valves. We consider cash a relief valve in a mental accounting sense because it is always available to pay essential expenses, such as the mortgage and tuition. The tactical allocation is a relief valve because it can satiate an investor’s cravings for action.

Investors should allocate more aggressively in the early stages of their lifecycle and gradually move to more conservative portfolios as they age. Throughout the chart, more color reflects less aggressive investments and less color reflects more aggressive. Once the investor is approximately five to ten years from retirement, they should begin the distribution phase and invest accordingly. This phase should include less aggressive strategic and tactical allocations as well as more cash.

STEP 4: ALLOCATE WITH A RISK FIRST APPROACH

Understand that risk matters, and the importance of risk management is twofold. First, the arithmetic of loss makes it clear that positive compounded returns come more easily if downside deviations are limited. For example, a loss of 10% requires a return of 11% to get back to even, which is not an unreasonable expectation. Meanwhile, a loss of 30% requires a gain of 43% to get to even and a loss of 50% requires a doubling to get back to where the investor started.

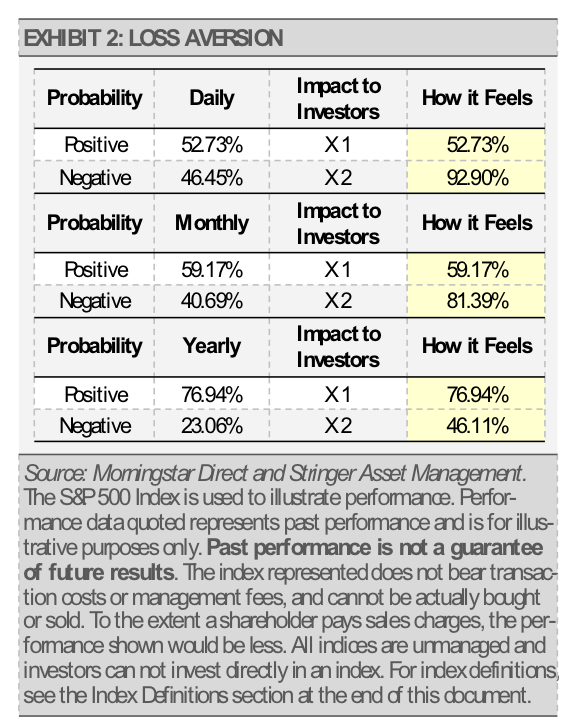

More importantly, losses have a larger impact on investor sentiment than gains. The behavioral economics concept of loss aversion refers to the tendency for individuals to be more sensitive to a loss than they are to a gain. More specifically, the pain of a loss is in some cases more than two times greater than the good feeling associated with a gain. When combining the pain of a loss with a bias towards action, investors can make emotional decisions in a down market, which is rarely a good choice.

While the probabilities of a loss small for fixed income investors, equity-oriented investors should understand how time and probabilities relate. For instance, the S&P 500 Index is just as likely to return a positive number as it is a negative on a daily basis.

However, if investors extend their timeframe, the probabilities of a positive return are greatly increased. Furthermore, we can illustrate the loss aversion problem by combining those probabilities with investors’ sensitivity to a loss. The discontent and impact felt by investors with a negative return on a daily basis is almost twice the satisfaction of a gain in their investment portfolio. The probabilities and resulting utility for equity investors does not turn to their favor until the timeframe is extended to about one year.

STEP 5: SATIATE CRAVINGS FOR ACTION

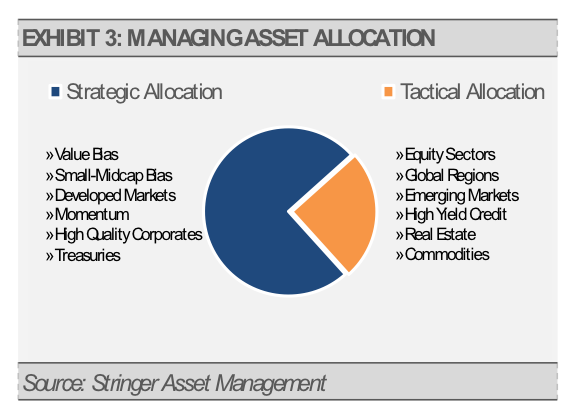

Many investors have a craving for action and we believe that there are opportunities for new investment or to play defense in every market. It makes sense that Financial Advisors should include a tactical allocation in their clients’ portfolios in order to attempt to take advantage of new opportunities or to quickly pare back risk, depending on the environment. These changes can help satiate their clients’ craving for action.

For example, within our strategic (longer-term) and tactical (shorter-term) allocations, we maintain specific biases that should benefit our clients over time. Our strategic allocations use market factors that we think perform best over the long-term. Conversely, our tactical allocations allow us to take advantage of short-term opportunities and manage risks in real-time. Furthermore, there are certain asset types that we favor for the strategic portion of a portfolio and others that we think are more appropriate for the tactical side.

STEP 6: HAVE A PLAN IN CASE OF AN EMERGENCY

Today’s 24-hour news cycle, where if it bleeds it leads, can drive investor emotions to extremes. Having a plan in case of emergency can help clients sleep at night. By this, we mean having a plan to reduce equity market exposure and increase defensive cash positions in anticipation of outsized market selloffs.

Importantly, this should be a stubborn plan. Attempting to time the market is not a fundamentally sound investment strategy. Nobel laureate William Sharpe found that market timers have to be correct over 70% of the time just to keep pace with buy-and-hold investors2. Since uncertainty is inevitable, a fundamentally sound investment strategy should alleviate the necessity to clear such a high hurdle.

The team at Stringer Asset Management has worked together for nearly 15 years on developing an investment management process with individual investors and their families in mind. Contact us to learn more about these and other behavioral economics strategies designed to help Financial Advisors and their clients realize better investment results, because at Stringer Asset Management, your success is how we measure ours.

This article was written by Gary Stringer, CIO, Kim Escue, Senior Portfolio Manager, and Chad Keller, COO and CCO at Stringer Asset Management, a participant in the ETF Strategist Channel.

DISCLOSURES

Any forecasts, figures, opinions or investment techniques and strategies explained are Stringer Asset Management, LLC’s as of the date of publication. They are considered to be accurate at the time of writing, but no warranty of accuracy is given and no liability in respect to error or omission is accepted. They are subject to change without reference or notification. The views contained herein are not be taken as an advice or a recommendation to buy or sell any investment and the material should not be relied upon as containing sufficient information to support an investment decision. It should be noted that the value of investments and the income from them may fluctuate in accordance with market conditions and taxation agreements and investors may not get back the full amount invested.

Past performance and yield may not be a reliable guide to future performance. Current performance may be higher or lower than the performance quoted.

The securities identified and described may not represent all of the securities purchased, sold or recommended for client accounts. The reader should not assume that an investment in the securities identified was or will be profitable.

Data is provided by various sources and prepared by Stringer Asset Management, LLC and has not been verified or audited by an independent accountant.

1Rubin, R. E. (1999, May 17). Treasury Secretary Robert E. Rubin Remarks to the University of Pennsylvania Commencement Philadelphia, PA. Retrieved from https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/rr3152.aspx.

2Sharpe, W. (1975). Likely Gains from Market Timing. Financial Analysts Journal, 31(2), 60-69. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4477805

Index Definitions:

Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Corporate High Yield Index – This Index provides a measure of the U.S. investment grade bond market, which includes investment grade U.S. Government bonds, investment grade corporate bonds, mortgage pass-through securities and asset-backed securities that are publicly offered for sale in the United States. The securities in the Index must have at least 1 year remaining to maturity. In addition, the securities must be denominated in US dollars and must be fixed rate, nonconvertible and taxable.

S&P 500 Index – This Index is a capitalization-weighted index of 500 stocks. The Index is designed to measure performance of a broad domestic economy through changes in the aggregate market value of 500 stocks representing all major industries.