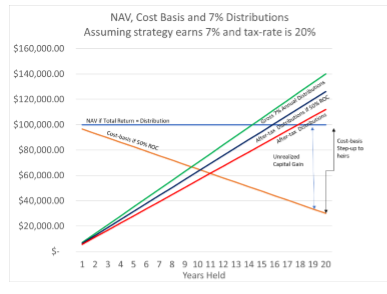

The following graph illustrates the effect by showing a $100,000 initial investment and holds the total return, distribution and tax rate constant to isolate the benefit of deferral.

If distributions are comprised 50% of return of capital, the investor’s cost basis declines steadily over the next 20 years, after-tax distributions increase and the investor can defer the realization of capital gains potentially indefinitely.

RETURN OF CAPITAL CAN DEFER REALIZATION OF CAPITAL GAINS

One of the benefits of the ETF structure is that it offers the potential to defer the realization of capital gains through the creation/redemption process of ETF shares. When ETF shares are created, they are sold to a special broker-dealer called an authorized participant (AP), who then sells them on the secondary market. Conversely, when ETF shares are redeemed, an AP redeems ETF shares that it has acquired on the secondary market.

Transactions between APs and ETFs generally do not involve cash. When an AP creates new ETF shares, it exchanges a basket of securities, called a creation unit, for shares of the ETF. The creation unit consists of all the securities that are represented by one share of the ETF. For example, in the SPDR S&P 500 ETF Trust (SPY), one share of the ETF represents a proportional share of each of the 500 companies in the S&P 500 Index. To create shares of SPY, an AP would buy shares of each of the 500 companies and exchange them with the ETF for shares of SPY. The process works in reverse when an AP redeems ETF shares, with the AP receiving the creation unit in exchange for ETF shares.

This is called an in-kind trade, since shares are swapped for shares. Because cash is not exchanged, the Internal Revenue Service doesn’t consider this a taxable transaction. This means that in a redemption, an ETF can “in-kind out” appreciated securities for ETF shares without realizing capital gains on the appreciated securities. In contrast, since mutual funds generally sell and redeem fund shares for cash, they may have to sell appreciated securities for cash in order to fund redemptions, thereby generating capital gains inside the fund that must be distributed to shareholders. The in-kind creation/redemption process is the foundation for the much-noted tax efficiency of ETFs compared to mutual funds.

While the ETF structure offers the potential to minimize realized capital gains inside the fund, investors may still incur capital gains when they sell their fund shares. Consider the example above in which ABC Fund pays out a $7,000 annual distribution with 50% of it consisting of return of capital. If the investor holds ABC Fund’s shares for two years and receives a $7,000 distribution each year for a total of $14,000, $7,000 of that would be taxed as ordinary income and $7,000 would be return of capital and not taxed. This would lower the investor’s cost basis to $93,000 ($100,000 minus $7,000 in return of capital over two years).

If over that period, the shares of ABC Fund earn $7,000 in investment income and experience $7,000 of unrealized capital gains, the investment would still be worth $100,000. Consequently, if the investor decides to sell his shares in ABC Fund at that point, he would incur a capital gain of $7,000 ($100,000 less his adjusted cost basis of $93,000).

By paying out a return of capital rather than selling appreciated securities to fund its annual distribution, ABC Fund avoids realizing short-term capital gains inside the fund on its appreciated securities and allows the investor to defer taxes on his investment appreciation until such time as he sells his shares in ABC Fund. If he holds his shares in ABC Fund for more than a year, he receives long-term capital gains treatment and pays a lower tax rate.

LONG-TERM BENEFITS OF USING RETURN OF CAPITAL

The investor can permanently avoid capital gains taxes on his unrealized gains by not selling the shares and leaving the investment in ABC Fund to his heirs. Under the federal estate tax, when beneficiaries receive property from an estate, the cost basis in the property is “stepped up” to its current value. Thus, if the shares in ABC Fund are worth $100,000 when the investor dies, the cost basis for the beneficiaries

becomes $100,000—even if the investor’s adjusted cost basis had been reduced to $93,000. This step up in the cost basis of the shares has the effect of eliminating taxes on the investor’s $7,000 of unrealized capital gains. The beneficiaries only pay taxes on share price appreciation above the new cost basis of $100,000.

CONCLUSION

Returns of capital are considered an inferior way to pay out corporate dividends because they do not come out of company profits and instead represent the return of an investor’s original investment capital back to the investor. In this context, returns of capital may indicate a company is generating insufficient earnings to fund its dividend.

However, in an ETF, a sophisticated fund manager can strategically use return of capital in a distribution to defer and potentially eliminate taxes on unrealized capital gains. Simply stated, money is fungible and investors who need to spend money should consider investment strategies and distribution policies that maximize the tax efficiency of their consumption. ETFs that incorporate return of capital as part of a distribution plan may be beneficial to investors seeking to defer or eliminate taxes on capital appreciation.

For more articles by Lawrence Carrel, visit ETFs for the Long Run.

For more market trends, visit ETF Trends.