The debt crisis that affected Greece, Portugal, Ireland, Spain, and Cyprus at different points after the global financial crisis of 2008 has done major damage to integration. In many countries we can find important political parties calling to leave the euro (even in Germany). If people had a vote, the outcome would be hard to predict. Many in northern Europe believe they have bailed out other countries that irresponsibly managed their economic affairs, spending more than what they had. At the same time, many people in the less-developed countries think the euro has mostly benefited Germany, the main exporter to countries outside of the EU, by allowing it to keep a devaluated currency relative to where the old Deutsche Mark would be —enjoying a fixed exchange rate within the euro area.

However, the euro and the EU should be analyzed separately. Beyond the euro, we believe people in all EU countries —with exception of the UK, of course— would still vote to remain in the union, if asked. Nevertheless, it is worrying that European institutions are now so distrusted by large swaths of the population, meaning the tide of public opinion could very well change in the future. This is partly a consequence of the debt crises in many member states.

Austerity policies, seen by many as imposed by Germany, have angered many EU citizens and political leaders. Moreover, the 2015 refugee crisis inflicted further damage. The latter was used as a main argument for the Leave campaign in the UK, and has fueled the prospects of its critics, some of which have won power at the national level (e.g., Italy and Hungary).

The euro, on the other hand, presents a much darker outlook. A couple of questions help to sum up our view. What if instead of bailing out Greece, a larger economy, like Italy or Spain, had needed those levels of assistance? What if that were to happen now? Would the voters be willing to rescue another country, at a much higher cost? What could the ECB do, if it has already set interest rates at zero, and embarked on an asset-buying program even larger (as a percentage of GDP) than the one undertaken by the Fed? We summarize our view in the conclusions.

What would a breakup of the eurozone entail?

There are many variables at play to try to make a succinct prediction of such an outcome. A good starting point is to think of currencies themselves. If each country were left with its own currency, with them starting at a 1:1 exchange rate, which is what the euro does today, what would happen? Clearly, the 1:1 exchange rate would not last very long.

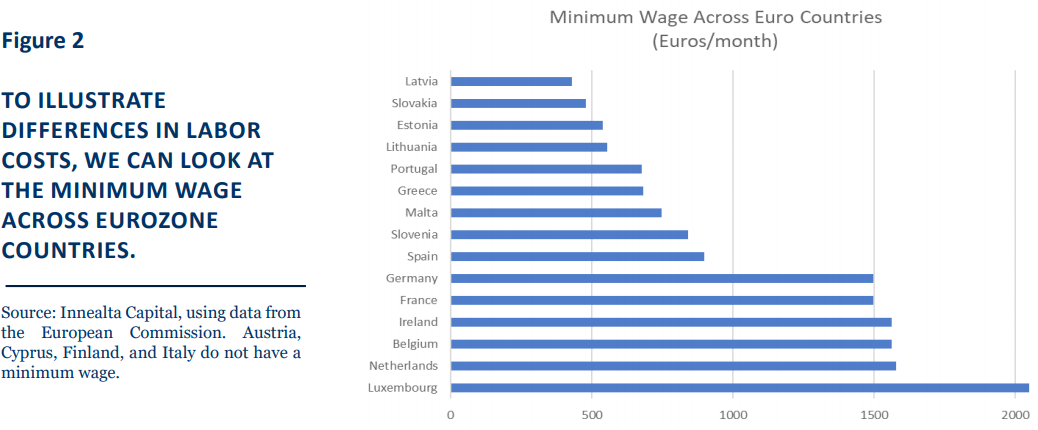

Many variables play a role in the determination of exchange rates. For example, current-account balances, debt levels, interest rates, inflation rates, economic growth, gap between actual and potential output, political risk, all of them matter. Yet we can safely make a few predictions. Germany’s currency would appreciate relative to the rest. Its savings levels, trade surpluses, and political stability would all push the value of the currency up. Countries in the south, with high levels of unemployment and weaker fiscal positions, would very likely see their currencies depreciate relative to the current euro. In this group we could count, at least, Greece, Cyprus, Italy, Spain, and Portugal. Other northern countries (Finland, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Belgium, Austria) should probably also see an appreciation. France would more likely than not also join this group. Even sharing the same currency, the cost of living and wages vary wildly as one moves across the euro area. Figure 2 compares minimum wages for 15 countries.

This means the weaker economies would become more competitive in international markets: they would export more and they would attract more tourists. However, these same economies would see their yields increase, even skyrocket (Greece, maybe Italy). There would be no winners in the short run, that is for sure. The levels of uncertainty would create tremendous volatility, investors would be scared, and a sell-off would ensue. Investors would incur further losses in those markets where currencies lost value against the dollar. The single market would not be as great as it now for trade if every country went back to its own currency. The banking sector would also suffer, with each country going back to its own set of rules, and the added frictions that different currencies would impose.

Conclusion

When looking at Europe, it is necessary to distinguish between the European Union and the euro. The common currency is one of the main features of integration, of course, but the EU preceded the euro, and it comprises more countries. It is perfectly possible to have an EU without the euro. This was exactly the status quo until 1999. Our outlook on the prospects of the euro area is dim. First, the eurozone was close to breaking apart after the sovereign-debt crises that affected many members in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. The EU was able to bail out Greece, but a bigger economy, like Spain, would have been a much bigger challenge. These days, the problems come from Italy, an even worse problem than Spain would have been. Italy is the third-largest economy in the euro area, with more than twice the levels of public debt required to be part of the common currency. What would happen if Italy defaulted? To add more fuel to the fire, the EU has rejected the Italian government’s recent budget, which will create even more tensions. The tugging between Brussels and Italy will continue in the future, that is guaranteed.

Moreover, the fact that the euro area is not a fiscal union — with a common budget and harmonized tax policy— will make sustaining the common currency in the future much harder. However, there is absolutely no path for a fiscal union. Voters from richer countries would surely reject it. Voters in Denmark have already refused to even join the euro, and people in Sweden are also opposed. Further political integration, also required to provide more support to the euro, is looked with suspicion almost everywhere. Voters in France and the Netherlands rejected the common constitution in 2005, before the financial crisis. It is certain that those levels of rejection would be substantially higher today. The refugee crisis has also contributed greatly to increasing levels of distrust towards Brussels.

All of these factors will continue to put pressure on the monetary union. It is more likely than not that within a decade the eurozone will look very different than it does now, probably with fewer members, if any. It may be hard to imagine a country leaving, just as it was hard to imagine a country leaving the EU until Brexit happened. Political volatility in the continent is increasing fast, casting doubt over a series of institutions that have been taken for granted for a long time. The “United States of Europe” is, currently, just a pipe dream. Thus, investors with allocations to eurozone countries should be aware of the potentially catastrophic losses associated to a collapse of the euro area, and be mindful of those when making asset allocation decisions.

(1) Four other countries participate in most aspects of it. This forces them to comply with all EU rules regarding those areas. These countries are Norway, Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Switzerland.

(2) The ERM, established by the European Economic Community in 1979, had the goal of reducing exchange-rate variability by semi-pegging currencies to a common unit. Semi-pegging means currencies were allowed to fluctuate within a range. The common unit was a first step towards the euro

Important information

This material is for informational purposes and is intended to be used for educational and illustrative purposes only. It is not designed to cover every aspect of the relevant markets and is not intended to be used as a general guide to investing or as a source of any specific investment recommendation. It is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instrument, investment product or service. This material does not constitute investment advice, nor is it a substitute for such professional advice or services, nor should it be used as a basis for any decision or action that may affect your business. Before making any decision or taking any action that may affect your business, you should consult a qualified professional adviser. In preparing this material we have relied upon data supplied to us by third parties. The information has been compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made by Innealta Capital, LLC as to its accuracy, completeness or correctness. Innealta Capital, LLC does not guarantee that the information supplied is accurate, complete, or timely, or make any warranties with regard to the results obtained from its use. Innealta Capital, LLC has no obligations to update any such information.

Cover picture, by Albert Häsler, taken from Pixabay (https://www[dot]pixabay[dot]com), is licensed under CC0 license. License details can be found at https://creativecommons[dot]org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/.

European map, created by Marcin Floryan, is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license. License details can be found at https://creativecommons[dot]org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/.