GTO’s secret sauce included impeccable timing, a heavy investment grade tilt, and a steadfast refusal to panic.

2020 was a chaotic year, especially in fixed income. But all the upheaval proved at least one thing: opportunity.

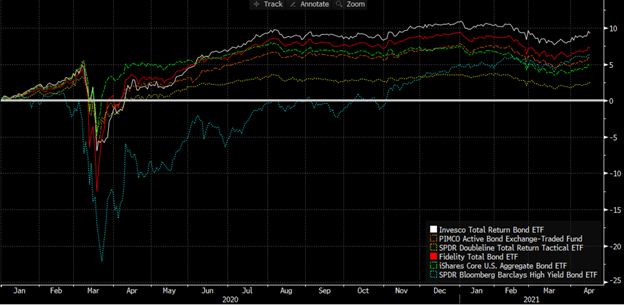

While most actively managed total return bond ETFs have posted fairly anemic returns since January 1, 2020, the Invesco Total Return Bond ETF (GTO) has gained 9.24%, handily beating every major competitor (and all major bond indexes, from Treasuries to high yield):

Source: Bloomberg

How did GTO’s returns manage to stay so strong during 2020’s chaos when so many other funds had wobbled?

To find out, I reached out to Matt Brill, the Head of Investment Grade Fixed Income for the Americas at Invesco, as well as a senior portfolio manager at the firm. Brill helped steer the ETF through all the ups and downs of the past year.

He was kind enough to give me an hour of his time to share his story. The following is a lightly edited transcript of our conversation.

Dave Nadig: GTO has crushed all comers lately, but it’s perhaps less well-known than some other total return ETFs out there. What sets your approach apart?

Matt Brill, Head of Investment Grade Fixed Income for the Americas, Invesco: With GTO, the goal is to look and act like the Bloomberg Aggregate [Bloomberg Barclays US Aggregate Bond Index, a.k.a. “the Agg”], but to do it better. We’ll still give you those core characteristics of a bond fund, but with more yield and more total return.

Nadig: So is the Agg a benchmark you’re trying to hug?

Brill: The only thing we’re benchmark-aware of is duration, because GTO is an intermediate bond fund, and investors expect that means a duration of 5-8 years. So, we might be a year long or a year short, but generally, that’s our range.

But fixed income is much more interesting than that makes it sound! Not all duration is the same. For example, right now we have a curve steepener on: we’re underweight the back end of the interest rate curve, [around]10 [years]out to 30 years; we expect rates to rise there. But with the Fed on hold through 2023, we’re overweight the 2-year key rate duration bucket. So while we’re in “the zone,” we don’t get there by just monolithically constructing for portfolio duration.

We really don’t look at [the Agg’s]portfolio weighting. I don’t need to own a certain percent of agency mortgages, or of investment grade. There is no high yield in the Agg, and we can own up to 33%. Structured securities are generally off benchmark as well. I’ve never looked at what any individual security is in the benchmark. We don’t look, and we don’t care.

Nadig: If you aren’t measuring for an average exposure on credit quality, how much of what you invest in wouldn’t be rated then?

Brill: Within the high yield portion, our goal is to help [GTO] outperform the AGG. For example, we’ll buy some of the highest quality high yield names, like Netflix (NFLX)—which a traditional high yield manager might not buy, because for them, it would bring down their overall yield. But I don’t care if it under-yields the highest-yielding high yield index. What I care about is that it’s more attractive than an investment grade bond that I can buy with very similar credit characteristics. I’m getting more yield; and when it gets upgraded to investment grade, then I’ll get the total return that’s comes with that upgrade as well.

Nadig: So, a bit of a “fallen angels” approach to the edges of ratings.

Brill: Generally, we’ll own a lot of BB names we think are rising star candidates, so the average credit quality of our high yield holdings will be much greater than the average of a high yield index.

Our credit quality in emerging markets is the same: We try to find the best-in-class emerging markets debt, [like]Alibaba (BABA), Tencent, Baidu (BIDU). These are $500 billion market cap companies, but because they’re emerging markets, they trade 50-75 bps behind Google (GOOGL) or Amazon (AMZN).

Nadig: Talk to me about how you went into March of last year. Obviously, few people were really predicting what happened in the markets then, but some people got in a little earlier, or acted a little quicker. What did that 90-day window around March 2020 look like for you?

Brill: It starts in Japan. Mid/late February of last year, a few colleagues and I went to Tokyo. By that point, everybody knew about the virus. It was the first time I’d ever taken a mask anywhere, and I had [used]hand sanitizer between each meeting. We talked on the ground to waiters and bartenders, and it was clear that everything was at 50% capacity because of restrictions.

Meanwhile, back home, our colleagues were seeing companies like Apple (AAPL) and Microsoft (MSFT) pulling their guidance. So we made the decision there was no upside in owning credit at that point. Even if this was just a minor blip, [we thought]valuations were very rich.

As bond managers, we’re always thinking about: what is the skew? What’s the upside and downside from here? [At that time], there was a lot of downside and very minimal upside. So in GTO, we reduced our credit risk in investment grade to 27% exposure. Honestly, I wish we would have gone lower! But I believe that that was lower than market weight at that time. It was the lowest we’ve ever been.

Nadig: That was a bit of a prescient dodge. But lots of folks managed to sell early, only to horribly mis-time the bounce.

Brill: And, obviously, everything started blowing up in the middle of March. But little by little, you started to see the highest quality companies come to market with new issues: Disney (DIS), Coca-Cola (KO), and Procter & Gamble (PG). Procter & Gamble, for instance, came out then with an issuance at the widest spread since the financial crisis, while at the same time you literally couldn’t buy toilet paper [because]demand was so high.

So we started wading in, buying the highest quality names within the investment grade space. Then the Fed came out on March 23rd and said they were going to start buying corporate credit for the first time in history. We said, “this is even better.”

Nadig: Did you look at the Fed’s buying list for what those underlyings were? I remember talking to a bunch of bond managers last summer who were on pins and needles every month when we got the report about which ETFs the Fed bought.

Brill: To me, [Fed-leading] was the no-brainer trade. It had to be a U.S. company [that the Fed bought], and I don’t think they could buy banks. So if they’re going to be buying, you’d want to go buy them [too]. And they bought the [bond]ETFs, and you can look through what the ETFs are buying.

So we pretty much put all our chips on investment grade, because we thought, “that’ll survive, no matter what.” It’s pretty much bulletproof, in our opinion. So we ramped up our investment grade exposure, from that all-time low of 27%, all the way up to 43%.

But we didn’t go into emerging markets or high yield, although we had some bonds that were fallen angels at that time fall into high yield. [So it might appear that] our high yield picked up just a touch, but that was all fallen angels. We bought a lot of investment grade bonds: the highest quality first, then the middle quality stuff. We caught the wave that came all the way back.

Now, there were some things we had to use deep credit research on—some of the re-openings, like Ross Stores (ROST). Companies like that were just enormous opportunities, but they had stores opening and little online presence, so there was pretty close to zero revenue. I had to take a leap of faith that if they got access to capital, it [would]help buy them time to kick the can down the road until the world improves. This was going to help preserve them. And we were starting to hear our credit analysts say, “they’re pivoting really fast.” These companies took a bath for a month or so, but they learned how to live within that environment.

Nadig: You said something that I think is really critical: these companies had access to capital, which bought them time. Do you think this was a disproportionate shaking out in the economy? Companies that already had a relationship with the Street were more likely to survive than companies who’d maybe been private or who had done very little issuance before, and therefore weren’t on people’s radars, even if they were AAA-rated or coming to market with a new issuance in April, etc.?

Brill: I think so. There was some discussion about the Fed program where, if you couldn’t get access to capital, you could go to the Fed for [some, at] what they viewed as a reasonable rate. Nobody ended up having to use it. So if you were a private company and you didn’t have financials, I think you still could have eventually gotten capital.

But companies used the 2009 playbook as well: once the market started opening up, they tendered for a lot of their frontend debt, then issued a lot of long-dated debt. At first, they drew down their bank lines, but once they realized they had access to the bond market, they issued a lot of debt. Then they realized maybe they don’t need all this debt, so they started tendering for it. As long as they felt they had enough cash, they could kick the can down the road. That was what they did in 2009, and I think many companies did it again in 2020.

Dave: You had seen this movie before.

Brill: Right. [So we knew that] the first companies to come with the highest quality – they were going to make huge concessions. Those were the names that you needed to pile into, and with significant size. If things continued to play out, then you would get more and more opportunities.

So, while we went to 43% Corporates, we did recycle a fair amount of capital as well. We rotated out of a lot of names, because there was so much good supply coming on that we literally couldn’t buy every deal. We would’ve run out of capital.

Nadig: The same thing happened on corporate balance sheets, right? Yes, you were getting good deals, but smart companies were also restacking their capital structure in a positive way.

Brill: They did it in stages. The first stage was to just get cash on the balance sheet. They said, “well, we’ve got this old 4.5% coupon outstanding, but we just borrowed at 3%, so let’s go ahead and take that out.” Little by little, all-in yields went lower and lower. As rates stayed low and credit spreads got lower towards the back half of the year, companies were tendering a lot of debt and replacing it.

That’s one of the key differences versus active versus passive. In passive, bonds go into the index at the end of the month, whereas we [as active managers]always try to use the new issue market as an opportunity.

Nadig: How proactive were you? Were you hunting for those new issues—or, as an established active shop, were they calling you? For example, back in the ’90s, getting a juicy new issuance was all about who you already knew.

Brill: It depends on the timing. At the worst time periods – say, for the airlines – it was every day we’d get the call: “Here’s the fleet we’re looking at, etc.” Meaning, there were a lot of calls that were essentially: “Here’s the collateral. What do you think of it? What loan to value [ratio]would you be interested at?”

So, yes, there are certainly times where having a good relationship with the Street is important. Those relationships are something you build up over the course of your career.

For example: a company came to us and wanted to issue a 60-year bond at the end of 2019. Nobody else would work with them on a 60-year bond. Then I pointed out that the math works out such that if you get enough yield in a 60-year bond, the company could actually default in 30 years and one day, and you’d have made more money than if just bought the original 30-year.

So Wall Street will come to you. You have to work with them to get the best opportunities, but most of the time there will be a food fight for bonds, typically when the times are good.

Nadig: Did you have any liquidity issues in all that capital recycling? Any issues with big inflows or redemptions?

Brill: My biggest fear through March was outflows. We had so much dry powder—our Treasury balance was the highest we’d ever had—and I wanted to be able to use that money for good purposes when times turned, rather than just paying off outflows for investors. But we didn’t see any material outflows at all.

Once we knew we weren’t going to get the outflows, we could then push into investment grade and ramp up the risk. If we didn’t have the dry powder, we would’ve had to sell investment grade bonds into a bad bid to buy more investment grade bonds—just spinning our wheels. But [as it was], we could sell Treasuries to buy investment grade bonds first.

Nadig: Let’s fast forward. Coming out of April, May, June, you’re sitting at over 40% investment grade. That’s a significant tilt. Where does that take you, as we go through the summer of 2020?

Brill: [Back then] we were saying that this is the second-best buying opportunity of our lifetime, and you need to take advantage of it! Eventually, of course, it no longer was. Credit spreads came back—and quickly. We looked at the valuations and said, “okay, this is still a decent opportunity—but no longer should we pound the table for everything.”

So we started scaling back. We moved our investment grade exposure from around 43% to the middle 30s range. We were still overweight in the summer, but it wasn’t really that generational opportunity anymore.

Nadig: Then we head into the fall.

Brill: By the time we got to the election run-up, we pivoted. We thought that the elections would go one way—but, more importantly, that there was a vaccine coming soon. I was convinced. I’m just a believer that science in America wins in the long-term. Then, within one week, you got the Pfizer announcement and you had the election results.

That made us shift into new three themes: reflation, reopening, and rerating. Reflation meant rates were going up and the curve was steepening; so we started adding more to high yield in emerging markets. Reopening meant travel and leisure: we had done some deals with airlines, but now we added names like Expedia (EXPE), and other high-quality travel and leisure names.

Last was rerating. We felt confident that the pendulum was swinging back into accelerating economic growth. So that means rerating bonds out of high yield and into investment grade. We increased our exposure to BB-rated names, as the high yield firms started issuing more debt. We tried to buy as many names as we thought would be coming to investment grade. A lot of high-quality tech names—huge, mega cap names like Crowdstrike (CRWD) and ZoomInfo (ZI), with $25 to $50 billion in market cap—are rated high yield. Twilio (TWLO) has $1 billion of debt, and they are a $50 billion market cap company! They just issued debt because they wanted to build out their capital structure. Possibly because, as we talked about earlier, you have to have a capital structure in place if you need to borrow money so that people are familiar with you.

Nadig: We spent most of this conversation talking about the corporate space. But that’s roughly 20-40% of your portfolio. What’s going on in the rest of your portfolio at this time?

Brill: Non-agency mortgages were an area that we had been overweight. We thought there was pretty good value there going into the crisis. But that was one of the areas that didn’t do as well, because everybody thought that we would go back to a housing market crisis, right? As time went by, they realized, no, this [moment]is actually really good for the housing market, because it means lower rates, and everyone’s stuck at home and they want more space.

So we did the work on what this all meant. And [we decided to]add agency mortgages, non-agency mortgages. We wanted to have the theme residential over commercial, though, so we didn’t add CMBS. We’re still cautious on CMBS.

Nadig: What about CLOs?

Brill: We do buy AAA CLOs, and by the third or fourth quarter we’d started adding more. But within that market, we’re generally playing at the top of the capital structure. CLOs are part of that reflation theme, as well: they’re going to participate in the accelerating economy with a floating rate instrument.

The one bond asset class I haven’t mentioned yet is taxable municipal bonds. Taxable munis were a great opportunity in 2020. You had all these AA-rated hospitals and universities that were issuing debt in mid-to-late 2020. These were 30-year bonds, too, so you get that spread duration.

That was an asset class that didn’t even really exist 10 years ago. The Trump tax code made it so you can’t refinance a traditional muni with another traditional muni; if you want to refinance early, you have to use the taxable market to do it. Looking at the ratings, these really were great opportunities.

Nadig: Okay, so, we talked the past and present. What about the future? How are you thinking about your positioning, given all the discussion around inflation?

Brill: For inflation, longer-term, three things are important: demographics, globalization, and technology. None of those three things have changed with the pandemic—and in fact, I would argue that technological improvement has accelerated. And all three of these things are deflationary, longer-term.

Nearer-term, you’ve got $1.8 trillion of estimated consumer dry powder in excess savings that we wouldn’t have had without a pandemic. People are stuck in the house. They can’t spend their money. For the longest time, they were afraid to spend money, because they thought they were going to lose their jobs. [Now] that money will get spent—and that’s even before the stimulus we just had.

So you’ve got probably $2.5 trillion or so of dry powder [money]that’s dying to get spent. I think near-term, you’re going to see very heavy inflation prints. In the economy right now, there isn’t enough staff at the hotel; there aren’t enough rental cars at the airport; and if you go to a restaurant, you can’t get a table. These companies will raise their prices, as everybody gets vaccinated and wants to spend all that money they’ve accumulated.

With near-term volatility, we’d use that as an opportunity to look to at longer rates. Right now, we are shorter rates and have a steepener on.

Nadig: So if the belly of the curve starts popping, you start to see the 10-year and 20-year sell hard. You’d look at those as long-term buys, right?

Brill: Yes. Because we don’t think anything has changed, but I certainly think it’s going to be hard to own a 1.6%, 10-year Treasury when you see a CPI print of 4%. If that happens, I think people are going to get nervous.

Nadig: Any thoughts on how the infrastructure bill–whatever version of it might eventually pass–impacts things?

Brill: The infrastructure is more of a heavy bleed, if you will: a heavy dosage of money, after money, after money, for 10 years. Longer-term, it’s part of the reflation trade.

We do think that oil and steel companies and the like are all going to benefit from this. And the infrastructure that Biden’s talking about isn’t just the traditional roads and bridges; some of it is broadband and tech.

But overall, I think that infrastructure is debt on the U.S. balance sheet. Longer-term, the country does have to pay back the money. And longer-term debt is generally a deflationary burden. Money that the country would have spent on other things now gets spent to pay down or service debt.

So I joke: you got the party this summer and you got the after-party with infrastructure. But after that after-party comes to the hangover. Hey, government? You’ve got to pay it back.

Nadig: Do you think it changes anything in the muni space at all? Because I’ve seen a lot of people wrestling with how the proposed infrastructure bill will impact the muni space, because traditionally infrastructure spending is primarily financed by municipal bonds, not direct DC spend.

Brill: I think there will be major demand for munis, because first off, I think individual income tax is definitely going up. Lots of money will flow into munis from that side of things. Then, on the infrastructure spending, yes, there’ll be a lot of projects done with muni debt, but also a lot of money in this recent stimulus plan will be given to local municipalities to help shore up their balance sheets.

Net, I think it means probably more supply and better fundamentals for me, and also demand coming in from individuals trying to manage their taxes as best they can.

Nadig: Last question: what should our audience know about your domain that they might otherwise gloss over, or just not really get?

Brill: I know that the fixed income market is three-dimensional. There’s credit curves, there’s rate curves, there’s sectors. There are asset classes. But the average investor just hears “the ten-year Treasury did this!” That never tells the whole story, because not all bonds are created equal.

There are so many ways to approach the fixed income space, and that’s what makes this fun and interesting.

For more news, information, and strategy, visit the ETF Education Channel.