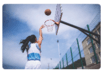

Amid speculation that stocks could be in for some bumpiness over the near-term, some investors may be considering exchange traded funds like the Invesco S&P 500 Low Volatility ETF (SPLV).

That’s a fine idea in its own right, but understanding how SPLV and other low volatility ETFs work is paramount in avoiding disappointment. For its part, SPLV, one of the funds that kick-started the “low vol” movement in ETF form, tracks the S&P 500 Low Volatility Index.

Today, SPLV holds 103 stocks, but the technical objective of its underlying index is to be home to the 100 S&P 500 members with the lowest trailing 12-month volatility. That’s an easy enough concept to understand, but where many investors run into dejection with funds like SPLV is with the expectation that these products provide strong upside capture. That’s not the objective.

“But there are trade-offs. Investors can’t have the best of both worlds,” writes Morningstar’s Ben Johnson. “Low-volatility strategies will tend to lag in bull markets. This is most evident in the downward slope of the line that spans the better part of the 1990s and more recently in the post-pandemic rebound. This is what investors in these strategies signed up for.”

Low Vol for the Long-Term

The point that Johnson is driving home is that investors need to know what they’re getting with low vol ETFs. The primary goal of a fund like SPLV is to keep drawdowns lower than a broad market or higher volatility fund when markets decline, not to be fully participatory in overt bull markets.

Knowing that, the next point investors need to account for is that an ETF like SPLV is most effective at smoothing out bumps over longer holding periods. That’s a positive because while stocks historically trend higher over the long-term, deep drawdowns are punitive to investor outcomes.

It’s possible that if an investor buys and holds an ETF like SPLV for an extend time frame, say five or 10 years or longer, the associated overall returns will be comparable to the broader market’s with less volatility. And as Johnson notes, “low volatility” isn’t the same thing as “no volatility.”

“Low volatility does not mean no volatility, just less. Low-volatility stock funds are still stock funds. They are designed to be less volatile than their selection universes, and there’s no question that they have delivered based on that criterion,” adds Johnson. “But it can be dangerous to equate ‘less’ volatility with ‘low’ volatility. The former is a more apt description and one that would better calibrate investors’ expectations. The latter better describes assets that would better diversify equity risk, like high-quality bonds.”

For more news, information, and strategy, visit the ETF Education Channel.

The opinions and forecasts expressed herein are solely those of Tom Lydon, and may not actually come to pass. Information on this site should not be used or construed as an offer to sell, a solicitation of an offer to buy, or a recommendation for any product.