Few topics are more polarizing at a cocktail party full of the investor class than anything related to environmental, social, or governance (ESG) informed investing. While it’s not quite the third rail, it’s definitely a danger zone because it lives at an uncomfortable intersection of modern capitalism and politics.

So, it’s not super surprising that the media seems to vacillate between four independent categories of narratives:

| Believes ESG Is “Good” | Believes ESG Is “Bad” | |

| ESG + α | “Steamroller approaching; get out of the way!” “Told ya so!” |

“We have to fix proxy voting!” “ESG is a Scam!” |

| ESG – α | “We must be measuring it wrong!” “Impure! Greenwashing!” |

“Let’s launch our anti-ESG fund!” “Told ya so!” |

This seems tedious.

ESG is a terrible acronym that can cover everything from green metals funds to funds that focus solely on proxy activism to ETFs focused on Catholic values and those trying to empower women. So it’s completely unsurprising when Elon Musk goes on a tear against S&P for kicking Tesla out of their ESG funds (even though Tesla’s regulatory overhang risk — a big issue in the “G” for ESG — is absolutely undeniably a real issue). One person’s clean energy darling can absolutely be another person’s poster child for reckless management.

How is it possible to reconcile this? By going back to the beginning.

Money Is the Imaginary Power System for Connected Humankind

Money is a heck of an invention, but make no mistake, it’s just a made-up thing that humans decided should exist. As soon as people started needing to barter more than they could carry, we needed some way to buffer power. At the species level, power is about survival, longevity, and genetic projection. A farmer has power because he grows surplus food. He can use that power to start a commune, to barter with the lady down the road who has too many chickens, or he can sell it for money, putting that power into a store of potential energy — money — which works as a store of power because we have created a system to enforce that through taxation, armies, and capitalist cultural hegemony. It’s pretty foundational to most of the modern world.

But the last 100 years or so have baked “money=power” much more deeply into the global ecosystem than is obvious from econ textbooks. The macroeconomic lessons of the great depression and WW2 were that governments’ ability to control money could redirect all that power in incredible ways — defeating monsters, sending folks to the moon, controlling a closed-state economy, or engendering globalism with an open one. But since WW2, the constant narrative reiterated to Americans (and much of the rest of the capitalist world) has been that money=power.

Politically and legally, America has done a lot to reinforce this. Whether it’s George Bush’s Ownership Society and the outsourcing of the social safety net (healthcare and retirement in particular) to monetary entities (corporations) (which we covered at some length a few weeks ago), or the assertion of Citizens United that money=protected political speech (and the ensuing monstrous flood of money into political campaigns that ensued), the march of modern society since the Dutch invented capitalism has been inexorably towards a singular truth: Money is how we move power through the species, and if you want to project power into pretty much any human endeavor from making art to fighting Zika, money is how you do it.

This doesn’t seem like a judgment call or a political position, but just an observation of the state of affairs. You can celebrate it or lament it, but to overquote David Foster Wallace — this is water. This is our world, which is a reason to get fired about financial education.

If Money Is Power, Investing Is Power Transfer

So after 100 years of educating the middle class that money is power, and developing a tax code that reinforces self-reliance through investing, we, as a country/society/species, essentially handed a bunch of power back to individuals. Just think about the shift from “defined benefit” to “defined contribution” retirement plans. In the old pension world, the corporation held onto the power until the last possible moment, giving the employee a time-shifted power transfer from working years to retirement years. In the newly defined contribution world, we hand people the power when they are younger and growing their lives and say, “Here’s some power, have fun incubating it,” instead of handling the time-shifting for them.

It should come as no surprise that a relatively large group of investors might decide that they’re going to use that power in ways that aren’t entirely what might have been planned by politicians and professional investors during the Reagan administration.

Barbaric Yawp or Modern Pleurants?

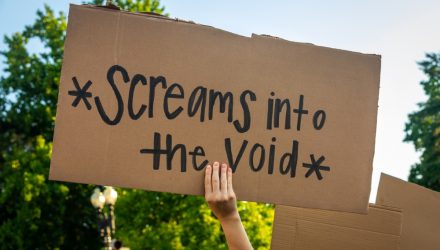

Thus, some portion of the global moneyed classes, whether they’re middle or upper-middle or Davos-flying, has chosen to take this power repository known as “investable assets” and essentially disgorge it at problems they believe need fixing. It’s exceptionally well-trod territory to point out the money just pouring in globally, but here’s the TL;DR: The global market cap of the roughly 60,000 listed equities is about $120 trillion. ESG assets (mostly but not entirely in equities) are about $40 trillion. There’s plenty of room for argument about the numbers and how much is “real” ESG and so on, but it’s pretty clear those are at least the ballpark numbers. Something probably less than a third but more than a quarter of the ownership of the global economy is at least nodding towards ESG principles, as loosely as you want to define them.

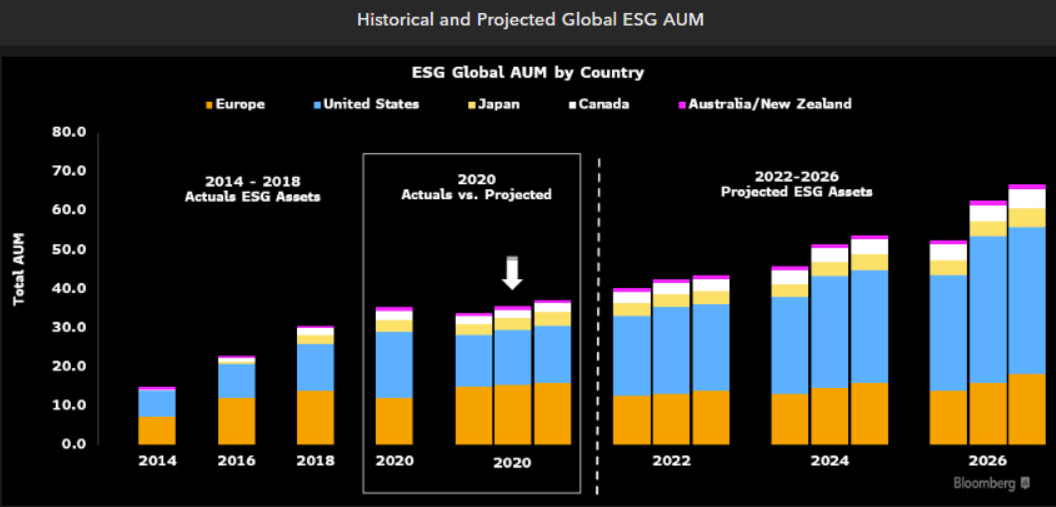

Importantly, financial advisors, arguably the tradespeople most in touch with money-in-motion over long time periods, are pretty profoundly committed to at least responding to client demands. As recently as last week, you, as advisors, told us that 28% of you saw your allocations to ESG going up in the next 12 months, vs. just 6.3% pulling back. Only 16% of you all reported having no ESG allocations, leaving the other 84% of you allocating at least some client assets based on ESG concerns.

VettaFi Advisor Poll, 24 June 2022

The question of whether ESG investing “works” is a deep topic, so much so that we penned an entire companion piece to this article to capture some of our thoughts and data, but the short answer is a deeply unsatisfying “It depends.” We could point out that the S&P 500 ESG ETFs are beating the S&P 500 ETFs handily over the past one, two, and three years, but shift the dates or benchmarks around, and I’m sure we could give you the opposite narrative.

Even pro-ESG folks don’t all agree that investing based on ESG factors should generate outperformance. In a now-storied piece from 2017 titled “Virtue is its own reward, or, one man’s ceiling is another man’s floor,” AQR head and hair-care product spokesman Cliff Asness argued that ESG nearly by definition must underperform and thus concluded:

“Frankly, it sucks that the virtuous have to accept a lower expected return to do good, and perhaps sucks even more that they have to accept the sinful getting a higher one. Well, embrace the suck as, without it, there is no effect on the world, no good deed done at all. Perhaps this necessary sacrifice is why it’s called ‘virtue.'”

…which is even more sobering when you consider that his firm, AQR, reportedly manages over $30 billion in dedicated ESG strategies.

Put another way, the projection of power through investment in ESG likely involves transforming that power into something non-economic — that’s actually the point. We told folks that money is power, we gave them some, and then they, perhaps simply screaming into the void, latched onto ESG as at least a way to make some noise, even if it just sounds like a “barbaric yawp over the roofs of the world.”

That’s not surprising to me at all. If you tossed us into a pit full of snakes with a stick, we would immediately apply our complete lack of experience and training to flail wildly around, just trying to keep the snakes at bay. A trained ophiologist with a better stick could probably segregate the snakes by threat and clean up house, but just because we don’t understand or like snakes doesn’t mean we wouldn’t try.

Of course, there’s a much more cynical viewpoint as well — that, like nobility who commissioned Pleurants to weep at the graves of the departed so they could get on with their lives, it is undoubtedly the case that some ESG investors are simply hoping to buy an indulgence from their own conscience.

Some ESG investors will have deep, thoughtful discussions with their advisors and make really sensible and conscious trade-offs between short-term and long-term power (money) needs, and some will grab a stick and start swinging, a version of screaming out the window that they’re mad as hell.

“It’s such a fine line between clever and stupid.”

— David St. Hubbins, “This Is Spinal Tap”

It’s entirely possible that ESG can be both brilliant and pointless at the same time. Holding two contradictory ideas in your head is a superpower, so it’s worth flexing. The $40 trillion in parked ESG assets should just be considered a $40 trillion exertion of power. It’s a transfer of potential energy from the end-investor to the corporations, with the full awareness that the return on that transfer may be non-economic (something we discussed in a companion piece today).

That may not make sense to you or the math of absolute returns at all costs. But it makes an enormous amount of sense from a social perspective. We took two generations (Gen X and Millennials) and not only convinced them that money is power but built new rules to drive the point home, and it’s those generations, largely, that took it seriously and are now choosing to use that power. It may be screaming into the void. It may be an enormously inefficient way to change the world. But it’s entirely logical.

The only question, really, is how you and your clients choose to exert what power you’ve been given. It is, as they say, your money, after all.

For more news, information, and strategy, visit the ESG Channel.