By Sara Rodriguez, Sage ESG Research Analyst

About Rio Tinto Group

The Rio Tinto Group is a multinational metals and mining company based in London and Australia. The company manages 60 operations across 35 countries and generates most of its revenue from the production of iron ore (60%), aluminum (23%), copper (5%), and industrial metals such as borates, titanium dioxide, and salt (5%). Smaller sources of revenue for the company include mining gold and diamonds.

Financially Material Factors Emphasized

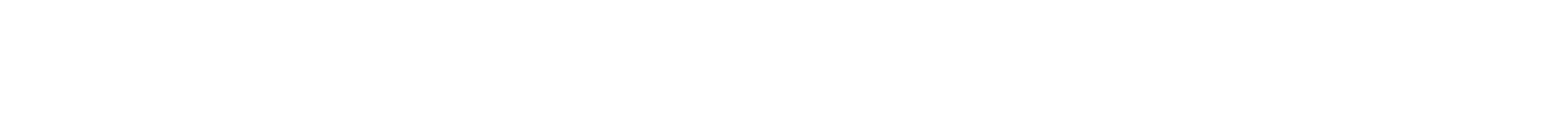

E – greenhouse gas emissions, energy management, water management, waste management, biodiversity impacts

S – human rights, rights of Indigenous people, community relations, labor relations, workforce health and safety

G – business ethics and transparency

Environmental

According to Boston Consulting Group, mining companies that have been early movers in addressing climate change have valuations that are, on average, 20% greater than those of their peers in the bottom quintile. Companies like Rio Tinto can benefit financially by focusing on decarbonizing their operations, identifying assets that are most at risk from physical climate change, and preparing for potential shifts in

demand for key minerals.

Much of the mining industry operates in harsh climate conditions, which are likely to be exacerbated by heavy precipitation, drought, and heat waves that are set to become more frequent and intense in the future. By distinguishing assets that are at risk of the physical impacts of climate change, mining companies can proactively address situations before they become a financial risk. Based on water stress data by the World Resources Institute, 19% of Rio Tinto’s operations are in high to extremely high stress areas, which means they are susceptible to drought. This makes it important for Rio Tinto to actively minimize water use and monitor the likelihood of drought near those high-risk assets. The company has adopted an adequate risk management framework to address its resilience to physical climate risk and aims to achieve local water stewardship targets for select sites by 2023.

Although climate change presents risks to the mining industry, it also presents opportunities. The number of metals and minerals we rely on in our everyday lives is staggering. Steel, aluminum, iron, copper, magnesium – these are all commonly found in the cars, cell phones, plumbing, and buildings we use daily. As consumer preferences change, so too will demand for metals and minerals. Lithium, cobalt, and nickel markets will grow as the electrification of the auto industry continues. Already in 2021, we have seen announcements from major automakers pledging to offer an increase or a complete transition to electric models in only a few decades. Copper, one source of Rio Tinto’s revenues, will be a key component in the wiring of electric cars and low carbon technology. In its 2020 Climate Change Report, Rio Tinto maps out the geopolitics, society, and technology possibilities of three different future carbon scenarios and the company’s approach to mining for each one.

While the company’s products stand to benefit from decarbonization, the mining of metals and minerals still requires the removal of massive amounts of rock, which uses a significant amount of energy. The mining industry is responsible for about 4% to 7% of global greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) created from direct operations (i.e., Scope 1 emissions) and from indirect purchased energy (i.e., Scope 2 emissions). As the Paris Agreement gains renewed traction, the mining industry will be critical to the achievement of its goal to substantially reduce global GHG emissions.

Rio Tinto is an industry leader in energy management and has already made great strides in reducing its GHG emissions. In 2020, 75% of electricity used at managed operations came from renewable sources (managed operations include those that Rio Tinto directly owns and operates as opposed to joint ventures where the company may provide capital only). Rio Tinto has pledged to become a net zero company by 2050 and plans to spend $1 billion on climate-related projects by 2025. Most notably, in 2018, Rio Tinto made the decision to sell off the entirety of its coal assets — making it the first major mining company to do so. This divestment serves to aid Rio Tinto in its transition to a low-carbon future and will protect the company against the negative consequences of a decrease in demand for fossil fuel products.

Rio Tinto’s coal divestment greatly reduced the company’s Scope 3 emissions, which are those generated from activities undertaken across the value chain, such as the use of sold products and transportation of products to market. These emissions are often not calculated by companies due to being speculative in nature; however, not only does Rio Tinto calculate its estimated Scope 3 emissions, but it also includes a detailed discussion of its path to reduction in its Climate Change Report. Rio Tinto plans to greatly reduce the carbon intensity that goes into transforming iron ore and aluminum into value chain products like steel, with the goal of eventually reaching carbon neutral steel and aluminum. The company also aims to reach net zero emissions from shipping (Scope 3 emissions) by 2050.

While energy management is highly financially material to mining companies, it is not the only environmental category that requires attention. Mining involves heavy machinery use, road construction, and the upheaval of rock structures. Subsequently, the ecology of a mining area is often damaged or destroyed during and after use. Rio Tinto aims to achieve no net loss in biodiversity from its operations, meaning finding a balance between the negative impacts on biodiversity and positive outcomes through mitigation. The company assesses all managed operations using an approach developed from the UN Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC) to prioritize operations based on their biodiversity sensitivity. Currently, 28 operations are identified as being within 5 km of a Protected Area, and 12 operations are in high priority sites (the company manages 60 operations globally).

One of the methods Rio Tinto uses to remediate biodiversity is through offsets. Like the ever-popular carbon offset, biodiversity offsets emerged as a way for land developers to counter ecological damage done at a project site by establishing a conservation project elsewhere. Today there are an estimated 13,000 biodiversity offsets worldwide. While offsets can offer an effective solution to a complex issue, there are social implications that arise. The rights of people directly displaced by mine-developed projects are generally well recognized; however, the case is less clear when it comes to those displaced by biodiversity offsets.

Biodiversity offsets are just one area that showcase the interconnectedness of environmental and social issues. The mining industry is distinctive in the sense that environmental damage often has a direct impact on communities of Indigenous people, shining a light on the issue of environmental injustice and making sustainability issues two-fold. An example is found in waste management, an important consideration in the mining industry. Mining requires the disruption of rock formations and creates waste rock that is leftover after the removal of metals and minerals. These leftovers take the form of a sludge known as “tailings,” which can become toxic due to the reaction of sulfide minerals when exposed to water and air to create sulfuric acid. This acid can seep from mines and waste rock piles into streams, rivers, and groundwater. This contaminates drinking water, disrupts aquatic plants and animals, and corrodes infrastructure, such as bridges. These problems are difficult and costly for mining companies and have the potential to damage a company’s social license to operate. Interestingly, Rio Tinto’s name literally translates to “tinted” or “red” river, as the company’s origins are tied to the discovery of a Spanish river stained red due to acid mine drainage.

Tailings storage is one of the biggest design decisions in the development of a mine. Tailings are often contained by large dams, the collapse of which can be severely consequential. In the past 10 years, there have been 31 recorded major tailings dams failures. One of the worst collapses on record took place as recently as January 2019 at a Vale-operated iron ore mine in Brumadinho, Brazil. Safety failures by both the mining company and its contracted engineers led 11.7 million cubic meters of liquid waste to inundate the valley at more than 43 mph, causing the death of 270 people and total destruction and contamination of the environment around the mine. One river is so polluted that even the mosquitos have ceased to exist. Sixteen employees face murder charges over the collapse, including Vale’s former CEO.

After the Brumadinho disaster and following the cues of other industry peers, Rio Tinto released an audit of its tailings storage facilities (TSFs). The company owns 158 TSFs globally, 40 of which were designated as having a “high” hazard consequence if they were to fail. None have been found to be unstable, and Rio Tinto has not had an external wall failure at a TSF for more than 20 years. The company has said that all tailings facilities with “extreme” or “very high” potential consequences will be in conformance with the Global Industry Standard on Tailings Management by August 5, 2023. Additionally, Rio Tinto has partnered with mining peer BHP to invest $4 million by 2025 to conduct research to improve tailings and waste management facilities.

Despite its efforts, Rio Tinto’s waste management history has not been without fault. The company previously partnered with industry peer Freeport-McMoRan to manage the Grasberg mine, which is in Indonesia and is one of the largest gold and copper mines in the world. The mine has been a point of contention for both environmentalists and human rights activists who accuse Freeport and Rio of decades of toxic waste dumping that has caused severe ecological and community damage. These actions resulted in financial repercussions for the mining companies involved, and in 2006, the Government Pension Fund of Norway (the world’s second largest pension fund) chose to exclude both Freeport and Rio Tinto from its investment portfolio (a divestment of $870 million). In 2019, the Government Pension Fund of Norway lifted the ban on Rio Tinto, citing the company’s selling of its interest in the Grasburg mine (it has since been sold to Indonesian mining company Inalum).

Social

Mining can significantly impact natural resources and ecosystem services that are the source of livelihood for many Indigenous people, in addition to being historically, culturally, and spiritually significant. Too often, laws do not adequately protect Indigenous lands. In fact, in May 2020 Rio Tinto legally destroyed two ancient and sacred rock shelters in the Juukan Gorge after being granted permission from the government of Western Australia. For the traditional owners of the land, the Puutu Kunti Kurrama and Pinikura (PKKP) people, Juukan Gorge was a site of cultural artifacts stretching over 46,000 years. The Indigenous group had an established relationship with Rio Tinto and had previously benefitted from mining activities, but leaders of the PKKP said they were misled about the company’s intentions to demolish the site and were not given permission to seek an emergency injunction after learning about the demolition only days before it was to take place.

This generated widespread international media coverage and public outcry, and Rio Tinto has faced significant repercussions, including three executive resignations, shareholder upheaval, a federal inquiry, and considerable damage to the company’s reputation and social license to operate. Rio Tinto’s future projects in Australia, Canada, and Africa require community and stakeholder approval, and negotiations will now be tougher, more drawn out, and more costly for the company.

This event was a sustainability catastrophe. The size and scope of the reputational damage to Rio Tinto make it difficult to gauge the sincerity of the company’s response; however, we do find that since Juukan Gorge, Rio Tinto has revisited and strengthened its policies around interactions and negotiations with Indigenous communities. Rio Tinto explicitly addresses the Juukan Gorge crisis on its website and accepts a degree of responsibility that is not often seen in corporate scandals. The company has updated its community relations approach, and actions taken to address Indigenous communities include recognition of cultural site significance and agreements with Indigenous communities regarding land access and mineral development. We believe the intention to do better exists, and such an event is unlikely to happen again.

Another important social issue in the mining industry is workforce health and safety. Mining presents a high level of health and safety hazards to its workforce. Underground environments are often harsh and unstable; there is limited oxygen flow and emergencies can be deadly. Despite its shortcomings in community relations, Rio Tinto does well in workplace health and safety. The company has achieved zero fatalities at its managed operations since 2018, zero health fines and prosecutions in 2020, and has reduced occupational illnesses and reports of mental stress.

The year 2020 emphasized the ‘S’ component of ESG, and we expect that to continue. How companies manage their relationships with their workforce and the communities in which they operate will be of financial consequence and directly linked to a company’s reputation and brand value.

Governance

Mining companies are required to work with governments worldwide to conduct business and gain access to mining reserves, making the mitigation of corruption and bribery of material importance. Rio Tinto’s code of conduct titled ‘The Way We Work’ clearly communicates that the company does not pay or accept bribes. The code of conduct sets standards to protect the company’s political integrity, and Rio Tinto states that it operates on a politically neutral basis.

The company has experienced controversy, however, and is currently under investigation by the UK’s Serious Fraud Office over suspected corruption in Guinea in 2017. Rio Tinto self-reported the payment in question and fired the executive in charge of the project at the time, saying they had “failed to maintain the standards expected of them under the global code of conduct.” While Rio Tinto will likely face financial repercussions, its transparency and willingness to cooperate with regulatory bodies showcase positive intentionality.

As a founding member of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative, Rio Tinto excels in transparency and disclosure. In 2018, the company pioneered transparency in tax payments within the mining industry, and in 2020 it released comprehensive financial and tax disclosures for each country in which it operates. The company is recognized for making its mineral development contracts with governments publicly available. Additionally, Rio Tinto’s sustainability report is published annually and is guided by multiple reporting standards, including the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) and Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB), and the data is externally assured by KPMG.

Sustainability and governance have direct ties at Rio Tinto, a strength that will help the company develop and maintain its ESG policies. Rio Tinto has a dedicated Sustainability Committee, which oversees key sustainability areas and monitors performance against targets. It also documents meetings and publicly discloses the topics covered. Rio Tinto’s chairman of the board is responsible for the company’s response to climate change, and in 2020, the remuneration committee approved including climate change progress in the company’s short-term incentive plan for executives, indicating a commitment to ESG.

Risk & Outlook

The mining industry is inherently at odds with the principles of sustainability. It is hazardous to the environment by nature and has the potential for accidents that can take a significant human and financial toll. At the same time, a shift toward a lower-carbon world will require technology that is contingent on those very resources the mining industry provides. At Sage, our ESG approach attempts to create a landscape representative of the entire economy. Rather than choose to exclude industries that are exposed to higher sustainability risks, our goal is to find companies that are presented with sustainability challenges and have the intentionality to innovate and adapt to future realities.

We find Rio Tinto to be a clear ESG leader in the mining industry. With overall strong environmental management, Rio Tinto’s divestment from coal not only positions the company to better align with the Paris Agreement, but also fortifies the company against the risks that fossil fuel assets face given shifting public sentiment and regulatory policy. While the company has remediation to do in the social category, we are cautiously optimistic that Rio Tinto will learn from the Juukan Gorge disaster and improve its transparency and community relations, especially considering the importance Rio Tinto’s governance practices place on sustainability and transparency.

The mining industry is necessary for everyday life and will serve to support a sustainable future. Despite the risks and challenges faced by the mining industry, we believe Rio Tinto to be adequate for our ESG strategies and give the company a Sage ESG Leaf Score of 3/5.

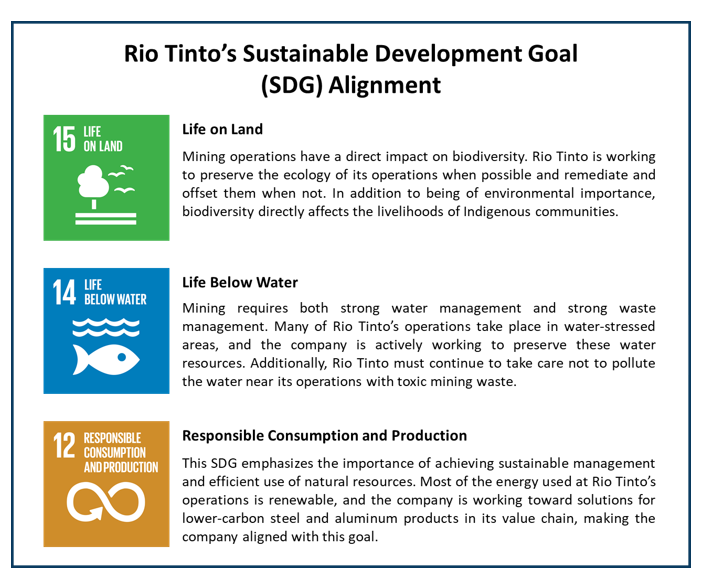

Sage ESG Leaf Score Methodology

No two companies are alike. This is exceptionally apparent from an ESG perspective, where the challenge lies not only in assessing the differences between companies, but also in the differences across industries. Although a company may be a leader among its peer group, the industry in which it operates may expose it to risks that cannot be mitigated through company management. By combining an ESG macro industry risk analysis with a company-level sustainability evaluation, the Sage Leaf Score bridges this gap, enabling investors to quickly assess companies across industries. Our Sage Leaf Score, which is based on a 1 to 5 scale (with 5 leaves representing ESG leaders), makes it easy for investors to compare a company in, for example, the energy industry to a company in the technology industry, and to understand that all 5-leaf companies are leaders based on their individual company management and the level of industry risk that they face.

For more information on Sage’s Leaf Score, click here.

Originally published by Sage Advisory

Sources:

- ISS ESG Corporate Rating Report on Rio Tinto Group.

- Climate Change Report 2020 Rio Tinto.

- “Sustainability” Rio Tinto.

- “Tailings” Rio Tinto.

- Kuykendall, Taylor et al. Net Zero: Mining faces pressure for net-zero targets as demand rises for clean energy materials. S&P Global. July 2020.

- Bour, Alexis et al. Mining Needs to Go Faster on Climate. BCG. February 2020.

- Vyawahare, Malavika. Madagascar regulator under scrutiny in breach at Rio Tinto-controlled mine. Mongabay News. November 2019.

- Gokkom, Basten. With its $3.85b mine takeover, Indonesia inherits a $13b pollution problem. Mongabay News. January 2019.

- Delevingne, Lindsay et al. Climate risk and decarbonization: What every mining CEO needs to know. McKinsey & Company. January 2020.

- Vyawahare, Malavika. Raze here, save there: Do biodiversity offsets work for people or ecosystems? Mongabay News. February 2020.

- Hume, Neil and Beioley, Kate. Rio Tinto in talks with SFO over bribery probe deal. Financial Times. July 2020.

- Senra, Ricardo. Brazil’s dam disaster: Looking for bodies, looking for answers. BBC Brazil. February 2019.

- Canfield, Michael et al. Can Mining Ever Be Ethical? Man Institute. February 2020.

Disclosures

Sage Advisory Services, Ltd. Co. is a registered investment adviser that provides investment management services for a variety of institutions and high net worth individuals. The information included in this report constitute Sage’s opinions as of the date of this report and are subject to change without notice due to various factors, such as market conditions. This report is for informational purposes only and is not intended as investment advice or an offer or solicitation with respect to the purchase or sale of any security, strategy or investment product. Investors should make their own decisions on investment strategies based on their specific investment objectives and financial circumstances. All investments contain risk and may lose value. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Sustainable investing limits the types and number of investment opportunities available, this may result in the Fund investing in securities or industry sectors that underperform the market as a whole or underperform other strategies screened for sustainable investing standards. No part of this Material may be produced in any form, or referred to in any other publication, without our express written permission. For additional information on Sage and its investment management services, please view our web site at www.sageadvisory.com, or refer to our Form ADV, which is available upon request by calling 512.327.5530.