Alpha has always been elusive in the stock market. Stock pickers have tried to produce it since the market has existed, but in aggregate they have been largely unsuccessful. Almost any long-term study that has been done has shown that managers who consistently produce alpha are few and far between.

In recent times, things have been getting even tougher. When the skill of managers rises and the tools available to them improve, the level of competition rises, and the ability to successfully create alpha for any individual manager falls. It is tough to argue that both of those haven’t happened in the past decade.

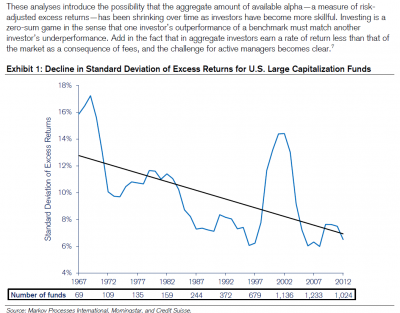

In 2013, Michael Mauboussin authored a piece for Credit Suisse titled, “Alpha and the Paradox of Skill“. In the paper, he wrote and showed the following:

Source: Alpha and the Paradox of Skill

I came across an interesting thread started by Ben Hunt from Epsilon Theory recently on Twitter and it got me thinking about what creates alpha and how that impacts the ability of managers to generate it in today’s market.

This is the tweet the started the discussion. Click here for high quality image of the tweet.

What Ben is saying is that if you want alpha, you need information that no one else has. If that is true, it has significant implications for not just factor investing, but for active management in general.

But is it true? Before we get to that, let’s take a step back and talk about what alpha is because the term in used improperly much of the time.

The Difference Between Alpha and Outperformance

Alpha is not outperformance over the market. Alpha is the portion of your return that cannot be explained by the risk you took. Or as Mauboussin puts in the highlight above, alpha is a measure of risk-adjusted excess returns. So a manager can beat the market and have negative alpha if their return was not commensurate with the risk they took, or they could underperform the market and have positive alpha if their return exceeded what was predicted based on the risk factors being used.

In the world of the basic Capital Asset Pricing Model, the process of figuring this out was fairly simple because there was one risk factor: beta. Under CAPM, alpha is the return you realized above and beyond the return required given the risk of your portfolio (as measured by beta). If your portfolio has a beta of 1.2, you are taking more risk than the market and CAPM would require a higher return to compensate for it. Only the return you achieved beyond that required return would be alpha.

The Fama French Three and Five Factor Models have made the situation much more complicated, though, and have also made alpha much harder to achieve. Why? Because these models don’tjust use beta as a measure of risk. They adds things like value and size and profitability as additional risk factors. With these new models, standard value investing goes from something that could be used to produce alpha to a risk factor similar to beta in the original CAPM. So as a value investor, you can no longer get alpha from just getting standard exposure to value. You now need to produce a return beyond the return that would be predicted by your exposure to value. The same is true for size, profitability and investment. If investing using these factors becomes beta, alpha is much harder to find.

But before I put you to sleep with my discussion of academic models, I will get back to my point.

The Sources of Alpha