By Kent Peterson, Joe Mallen & Chris Shuba, Helios Quantitative Research

When considering how currencies affect US $ portfolios, one must think about four things:

- Buying a foreign currency asset is a bet that the US $ will decline.

- The longer-term contribution of currencies to portfolio returns and volatility can be substantial.

- Some currencies have hidden regime jumps or shock risks.

- Will the US $ decline or rise the currency you invest in.

First, quite unlike stocks or bonds, currencies have no inherent value, only relative value, and when you make a relative value investment, you bet on one instrument rising more than another. That is because a currency only has value relative to what it can be exchanged for, whether that is the Japanese Yen, Gold or Bitcoin. Thus, putting money in a foreign currency means that you are implicitly expecting that currency to rise relative to the dollar, or for the dollar to fall relative to the currency that you bought.

For example, when you buy a broad non-US ETF like SPDR® MSCI EAFE StrategicFactors (QEFA), you assume that over time a diversified basket of global stocks will rise, and simultaneously assume that the US $ will fall in value. The changes in both the portfolio of stocks and the portfolio of exchange rates affect your P&L. In the example given, let’s say it’s a global stock market holiday and every equity market in the world closes for a 4 day weekend, but the currency markets remain open. Over that long weekend, the value of the stocks in QEFA will remain unchanged, but a 3% decline in the value the US $ relative to the currencies in the ETF will cause the value of your investment in QEFA to increase by 3% in dollar terms.

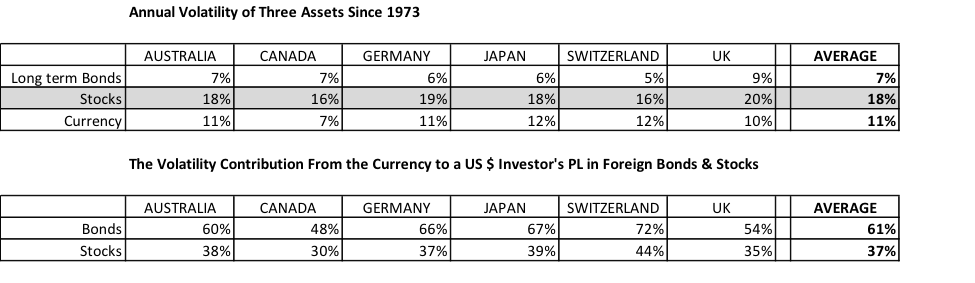

Second, while one might not think that exchange rates contribute to a long-term investment in an asset in another currency, the fact is they do. Consider the table below, which shows the annual volatility of the exchange rates of several countries vs. the US $, as well as the annual volatility of long-term bonds and stocks in the same country.

As you can see in the first table, Annual Volatility of Three Assets Since 1973, on average, the annual volatility of long-term (10 year) bonds in major developing countries has been about 7% vs. 11% for the currency. For stocks, the average annual volatility has been 18% vs. 11% for the currency. However, it is the second table, The Volatility Contribution From the Currency to a US $ Investor’s P&L in Foreign Bonds & Stocks, that tells the real story. On average, 61% of a US investor’s foreign bond P&L is determined by changes in the exchange rate, with only 39% coming from the performance of the bond itself. That is the majority. So, if you buy foreign bonds, it makes sense to hedge. With stocks, more than a third or 37% of a US investors P&L is driven by the currency change. Put another way, 37% of your foreign stock P&L is being determined by a factor that is extremely hard to predict.

![]()

Third, currencies occasionally make large, unexpected moves. These large changes are usually a currency devaluation relative to the US $, though not always. Latin American currencies, in particular, have a long and colorful history of dramatic collapse. Devaluations naturally cause a US $ investor to lose money on the currency part of their investment. Also, devaluations are usually inflationary and negatively impact holdings of local bonds, because local interest rates typically will rise. The impact of a currency shock on local equities is not always as predictable. Stocks that are highly dependent upon local or foreign currency debt, fall as rates rise and their foreign debt obligations increase, but an export company with little debt will likely see its share price skyrocket because the firm is now internationally more competitive.

For US investors, currency shocks are not always an emerging market issue. In the last few years, the UK and Switzerland have both experienced significant sudden changes in their currency value, because of the Brexit vote and an abrupt change in Swiss Central Bank policy. Should Denmark suddenly decide to uncouple the Krona from the Euro, or Hong Kong or China decide to make their currencies more free-floating, there would be massive changes in the exchange rate. These large potential changes in currency value, whether in emerging markets or the developing world are something investors need to be aware of.

Finally, one must consider the future direction of the US $. If it declines, foreign currency investments gain in dollar value, and if it rises, these same investments decline in dollars.

On the one hand, the US $ has some major pluses. For now, at least, it remains the world’s reserve currency. Our relative geographic isolation means the US is where funds typically come in times of geopolitical trouble.