By Frank Holmes, CEO and Chief Investment Officer for U.S. Global Investors

It’s official: Donald Trump has become only the fourth president in U.S. history to be the subject of a House impeachment inquiry.

I won’t say much on this, as the details of the inquiry are still unfolding. Plus, it’s an extremely divisive topic. Less than half of Americans support Trump’s impeachment, even after the news broke of his call with Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky.

I will say one thing. If history is any guide, it’s highly unlikely that Trump will be convicted of any impeachment charges, especially with Republicans in control of the Senate. The only two presidents who have ever faced such charges, Andrew Johnson and Bill Clinton, were both acquitted. Richard Nixon, as you know, resigned before articles of impeachment could be drawn up.

I don’t believe investors have too much to worry about in the short term, despite Trump’s warning that “markets would crash” if he were impeached. “Do you think it was luck that got us to the Best Market and Economy in our history,” he tweeted this week. “It wasn’t!”

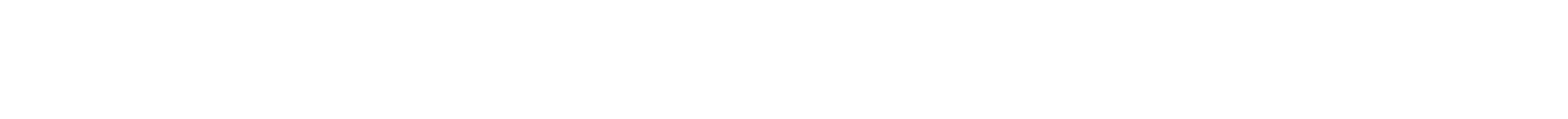

The sample size is small, but history shows that impeachments have had minimal impact on markets, and outcomes have been inconsistent. Stocks slid in the months following the start of Nixon’s impeachment inquiry, but far more important factors were at play, including the collapse of the Bretton Woods monetary system, the 1973 oil crisis and the start of the 1970s recession. In Clinton’s case, stocks ended up nearly 40 percent 12 months after the House announced its plans to impeach. But again, context matters. The U.S. economy was strong in the late 90s, and we were at the tail end of one of the longest equity bull markets in history.

The scenario today looks very much the same. The U.S. economy—though it may be showing some cracks—is still going strong. Stocks have so far shrugged off threats of impeachment. Going forward, I would place the blame of any potential market weakness on other factors, from the global economic slowdown to ongoing trade tensions between the U.S. and China.

Germany on the Cusp of Recession

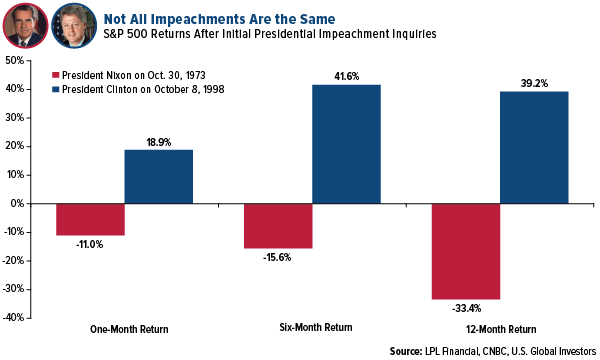

Indeed, if we look overseas, there’s much more that could rattle markets than U.S. political theater. Germany, for instance, may be on the cusp of recession, if it has not already entered one. The preliminary purchasing manager’s index (PMI) for September shows that the manufacturing sector in the world’s fourth-largest economy is contracting at its fastest pace since the depths of the global financial crisis a decade ago. The flash PMI registered 41.4, an alarming 123-month low.

“The manufacturing numbers are simply awful,” commented Phil Smith, principal economist at IHS Markit, which produces the monthly report. “All the uncertainty around trade wars, the outlook for the car industry and Brexit are paralyzing order books.”

Car sales have been slowing across Europe for months now, as I’ve written about before. In August they were down a whopping 8.4 percent year-over-year, according to the European Automobile Manufacturers Association (ACEA). This has been a drag on Germany’s important automotive manufacturing industry, Europe’s largest and the world’s fourth-largest by production.

Suppliers are feeling the pain as well. Continental AG, the Hanover, Germany-based manufacturer of auto parts, said this week that as many as 20,000 jobs were at risk over the next decade as plants will be closed not only in Germany but also Italy and the U.S.

Nervous investors have run for cover in the German bond market, where yields across the entire yield curve are currently trading in negative territory.

Helicopter Money Ahead?

A record $17 trillion in global debt now carries a negative yield, which is equivalent to about 20 percent of world GDP, according to a recent report by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS). The banknotes that the growing acceptance of negative yields has become “vaguely troubling.”

Just as troubling is the expanding level of global debt, which is now the highest it’s ever been in peacetime, according to Deutsche Bank’s recent analysis of 12 major economies. These dozen economies collectively have an average debt-to-GDP of 70 percent, the highest level in 150 years outside of a world war.