In case you missed some of the exciting action amidst the carnage yesterday, the Bond market, and specifically, bond ETFs had an interesting day. The headline, for some folks, is the seeming insanity around the difference between the Vanguard Total Bond Market ETF (BND) and it’s mutual fund brother (VBTLX).

Vanguard funds provide a laboratory for the differences between mutual funds and ETFs, because Vanguard, unique among ETF issuers, has ETFs which are share classes of the same pool of assets that other funds are part of. So under the hood, the actual portfolios of the two funds in question are the same – they just have different pro-rata ownership of the same pool.

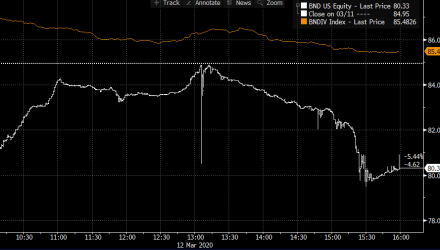

So what’s the buzz? Well, here’s a chart of the two funds Net Asset Values over the past month or so.

Deeply boring. Nothing to see here. I mean, sure, the last few days have been a bit rough, with the Net Asset Value down a few percent, but clearly, the reported NAV of both funds is doing the same thing. That’s not what has people confused; this is:

This is the Net Asset Value, still in white, alongside the last recorded price for the ETF as it traded on the open market, and low and behold – a discount! The ETF, as traded by investors, is simply below its fair value at the end of the last three days, a little at first, and then a lot yesterday. So what’s going on here?

This is the Net Asset Value, still in white, alongside the last recorded price for the ETF as it traded on the open market, and low and behold – a discount! The ETF, as traded by investors, is simply below its fair value at the end of the last three days, a little at first, and then a lot yesterday. So what’s going on here?

Bond Pricing

At it’s simplest, all that’s going on here is that Authorized Participants — the ones who are in the business of arbitraging out precisely this kind of discrepancy have made independent assessments of the state of BND’s holdings and come to the same conclusion: the NAV is wrong. They believe that the *real* price of bonds is much lower than the advertised price in that NAV.

Put another way, to make money off this gap, an Authorized Participant has to go out into the market and buy a pile of shares of the ETF, while simultaneously selling all the bonds it knows it will take delivery of when they hand their collection of BND shares into Vanguard for a redemption. That would let them “sell high” (selling the bonds) and “buy low” (scooping up those ‘cheap’ ETF shares.)

But they didn’t So we can conclude that nobody in the market believes they can make that trade work. They know that when they have to SELL the bonds, they’ll get prices that are much more in line with the price activity in the ETF than the magical Net Asset Value line that would imply a profit.

How does this happen? Because Net Asset Values for Bond ETFs and Mutual Funds are always wrong. Every fund has a pricing policy of some sort, approved by the fund board (sadly, it’s not available easily to investors). That pricing policy says things like “at the end of the day, we’ll go to three bond pricing services, get a bid on each bond, and take the midpoint unless the bond in question has traded within 10 minutes of the equity market close.”

They do this because the chances of any individual bond issuance just happened to trade contemporaneously to the close is low, so they need something to estimate what the fund would be worth, right then. These bond pricing services are themselves giant algo machines, which look at comparable bonds (duration, credit, liquidity, etc.) and proxies for market sentiment (futures, other ETFs) and then make a guess. That process is not millisecond perfect, it’s inherently lagged. And in times of stress, we often see disconnects between bond ETFs, NAVs, and closing prices.

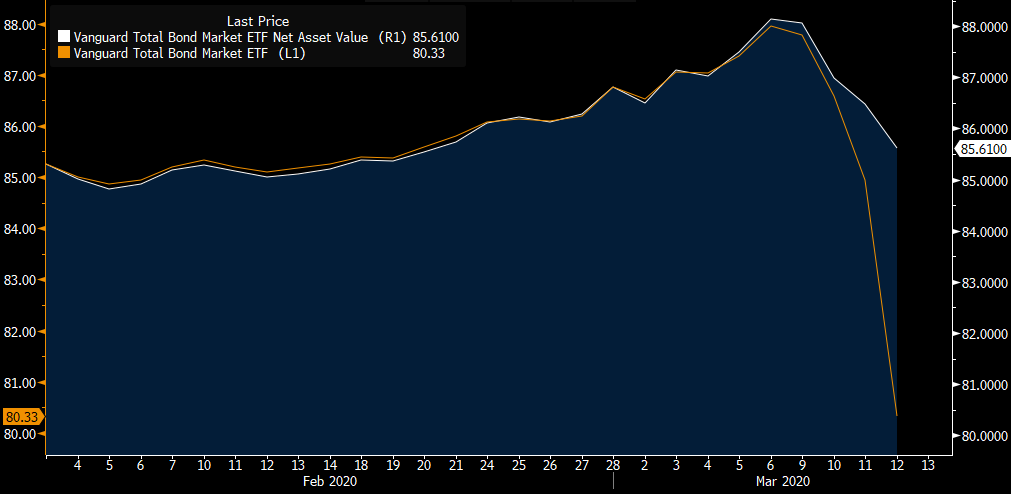

Importantly, this is not unique to Vanguard. We see the same action in BND’s biggest competitor, iShares Core U.S. Aggregate Bond ETF (AGG):

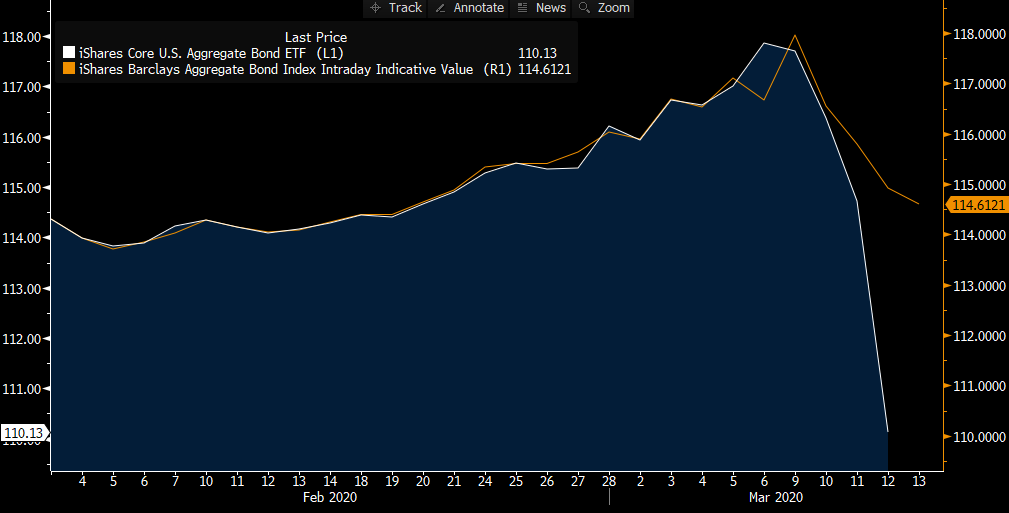

And just as important, none of this was a “surprise” to ETF traders. Both funds traded consistently below their advertised indicative NAVs all day as well (in this rare case, INAV has some small value as a comparison, but is even less reliable than NAV).

OK, a few blip trades in there, but it’s hardly like this is one surprise closing trade or bad auction. No, this is the market doing what it does — leaning on ETFs for price discovery in times of crisis.

OK, a few blip trades in there, but it’s hardly like this is one surprise closing trade or bad auction. No, this is the market doing what it does — leaning on ETFs for price discovery in times of crisis.

Who’s Right?

“But Dave,” I hear you say. “This sounds like horsepucky. You’re just defending the ETF!”

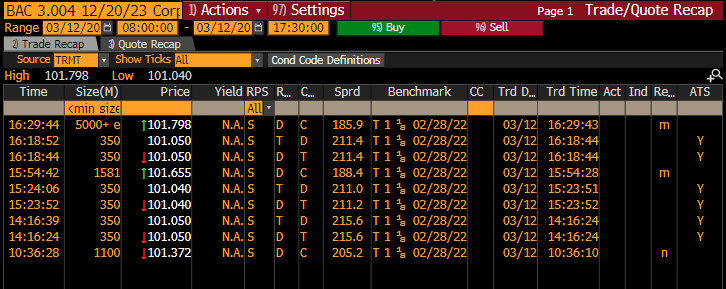

Honest, I’m not. ETFs, like BND, provides basket liquidity when the underlying liquidity is gone. How gone? Here’s a random, middle-of-the-basket position that an AP would have had to believe they could dump to arbitrage out this position. It’s a simple piece of Bank of America paper, due in 2023 with a 3% coupon. Here’s the blotter for yesterday.

Nine trades. That’s it. And since the first of the year? This particular bond has only traded 336 times. So, surprise surprise, APs are willing to let the gap widen out just a weeeee bit more on a historically volatile market day, knowing there’s nobody who’s going to take their call trying to unload their newly acquired chunk of BA paper. Ditto the other 50 corporate bonds or so in the redemption basket.

What’s “fair value” here? I’m 100% convinced it’s the ETF closing price. That’s the price at which investors were willing to make trades. Who wins or looses from this discrepancy? It’s pretty simple. If you were a mutual fund shareholder who decided to get out of your Vanguard Mutual Fund bond position yesterday, well, congratulations, you received 5% more than you deserved on your sale. If you decided to get into that fund, well, condolences, you got hosed. You overpaid by 5%.

And if you were an ETF investor? You got exactly what the market believed you deserved, on either side of that trade. Exactly as you should.

—

All charts from Bloomberg. You can find Dave on Twitter @DaveNadig. For more Fixed Income ETF coverage, check out our Fixed Income Channel.