Farnam Street letter to investors for the month of October 2018.

The Arrogance of Investing

Buying a stock is an act of sheer arrogance. It’s easy to forget, but there’s always someone on the other side of every trade. When you buy, you are saying, “What a dummy! I can’t believe they parted with their ownership of this company for such a low price. I must be smarter / more-informed / more-disciplined than they are. What luck!”

Every time you sell, there’s the same arrogance: “I can’t believe they took that company off my hands for such a high price! I must be smarter / more-informed / more-disciplined than they are. What luck!” The time frames matter: you can be right in the short-term and wrong in the long-term, or vice versa. But in nearly every instance, someone is right and someone is wrong when making a trade. How sure are you that you aren’t the dumb money on the wrong side of the trade? Warren Buffett is fond of the poker aphorism: “If you’ve been in the game thirty minutes and you don’t know who the patsy is, you’re the patsy.”

Mr. Market Revisited

Warren Buffett’s mentor, Benjamin Graham, crafted an allegory to explain market dynamics and help us understand who we’re up against. Graham asked us to imagine we are one of the two owners of a business. The other owner is a fellow named “Mr. Market.” Every day, Mr. Market offers to sell us his share of the business, or to buy our share. Mr. Market is a manic-depressive; his estimates of the business’s value bounce off the guardrails of dire pessimism and hopeful optimism. Although his moods can be extreme, he’s still an accommodating chap. Although we usually decline his offer, he happily shows up the next day with a new one. It’s our job as investors to understand his strengths and weaknesses and take advantage of his mood swings.

Your humble author would like to assume we aren’t the patsy at the poker table, but how do we know? Who is on the other side of the trade from us? Who is Mr. Market today? Let’s dive in and find out…

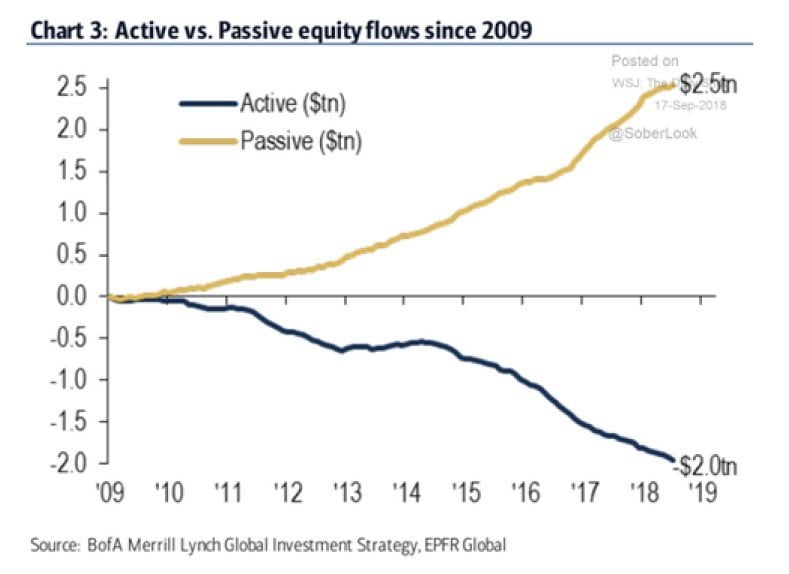

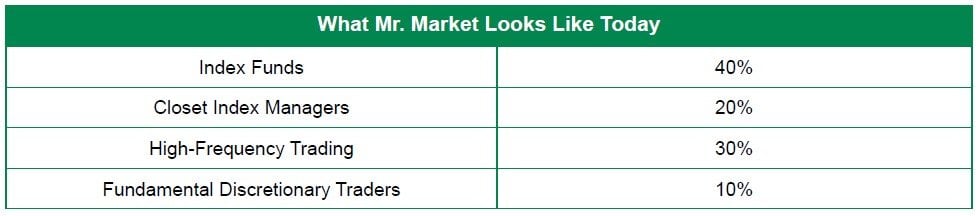

Roughly forty percent of U.S. trading these days is exchange-traded index funds. Indexing giants like BlackRock and Vanguard now own vast swaths of the market and are the largest shareholders in nearly all the major companies in the S&P 500. The massive flows from active to passive in the last decade are measured using the t-word.

By definition, index funds have little interest in the fundamentals of the businesses they hold. They are price indiscriminate: when money comes in the door at Vanguard, they go buy more of everything in the index. Flows trump fundamentals.

Indexing creates some odd structural perversities:

- Many indexes base their allocations on the float (aka availability of stock to buy and sell). If Warren Buffett bought more shares of Berkshire Hathaway in his personal account, thus reducing the available float, the index fund would penalize Berkshire and want to own less BRKA. Wait, Warren likes the price enough to buy personally, and now you want to systematically own less? Raise your hand if you think that makes any sense.

- Due to the aforementioned price insensitivity, some weird market dynamics have developed. The average U.S. stock is in 115 different indices (there are a lot of indices out there). Stocks which are in more than 200 indices are 2.5x more expensive than stocks which are in less than 75. Said more simply, if you’re a darling that’s included in a lot of indices, Mr. Market wants you, price be damned.

- The Biblical flood of passive dollars has driven up the prices of these companies, making the index itself go up, which then attracts more passive dollars. The “proof” of rising prices creates a virtuous circle of momentum. (Remember this one with U.S. housing in 2006?) If a company is an “indexorphan” and isn’t chased by passive money, Mr. Market hasn’t been very interested. The odd pressures from indexing create fault lines of opportunity for value-conscious investors. However, they’re difficult to realize until the tide of passive money abates and companies are judged based on their business prospects, not which index they belong to.

- Rory Sutherland recently observed: “The genius of markets lies not only in aggregating people’s preferences but also in aggregating choices made in a wide variety of messily different contexts, and with a variety of different decision-making paths. The danger is that if you make the informational context the same for everyone, and the decision-tree the same for everyone, the information the market receives will increasingly reflect that artificially narrow context, so will no longer reveal the wider preferences of market participants. The individual decisions may seem better, but the market will be dumber overall.”

Pause for a moment to imagine this passive tsunami receding. A change in psychology toward fear upsets the marketplace. Rest assured it will happen again, and only hindsight will show the match that lights the fuse. Safety is now prized and a pessimistic Mr. Market hates his “risky” stocks. The index funds don’t care what prices their shares fetch, by mandate they have to get out. Now. Selling pressure crashes prices, begetting more fear and more selling. A once virtuous cycle turns vicious.

If it’s like previous downturns, we may pessimistically undershoot the fundamentals when the blood hits the streets. (We’re overshooting the fundamentals with optimism today.) Sounds like it will be a scary time to be an investor, right? Except, that will be when FSI earns our keep. Cross your fingers for this generational buying opportunity. Or better yet, send cash. Fortunes will be made, and we’ll be participating en force when the tide shifts and patience gives way to action. We’ll be talking clients off of a different ledge at that point–such is the nature of the advisor’s role.

No one knows how long this current indexing insanity can last. I’m willing to admit it could be a nightmarishly long time (please, no). But eventually, the fundamentals of a business will matter again. My hunch is we’ll scratch our collective heads and wonder why anyone thought all this passive indexing made sense. “If everybody indexed, the only word you could use is chaos, catastrophe. The markets would fail.” – John C. Bogle, founder of the the first index fund

To recap, forty percent of Mr. Market is flat-out index driven. That leaves sixty percent as “actively managed,” meaning managers appraising businesses. Sixty percent is misleading though, as a surprising number of actively-managed funds are actually closet indexers. Many aim to just do what the index does, and there are good economic reasons for their hiding in the closet. Managers don’t want to lag too far behind the benchmark for fear of losing their jobs. Screw the fundamentals, I have to own FANG or I’ll get fired. The managers are doing what makes sense for themselves, though not their clients. As J.M. Keynes quipped, “Worldly wisdom teaches that it is better for reputation to fail conventionally than to succeed unconventionally.”

Researchers have devised metrics like “active share” to identify these closet indexers. Active share is the percentage of a portfolio’s holdings that differ from the benchmark index. A high active share means the fund manager is taking a chance and aiming to be different than the index. At FSI, we don’t have a specific benchmark to measure active share against, but one look through our portfolio and it’s clear we score off the charts and we own a lot of those neglected index orphans. They’re the only businesses on sale these days.

What’s the rest of the industry’s active share look like? Seventy percent of U.S. mutual fund assets are held in funds with an active share less than 80%. We can safely throw at least another twenty percent of “active” managers back into the index bucket due to hiding in the closet. That accounts for sixty percent, leaving us forty percent of Mr. Market to still classify.

It’s hard to pin down the exact number, but roughly thirty percent of what’s left is made up of highfrequency trading. These are computer algorithms which buy and sell in milliseconds, mostly to each other in a strange game of lightning cat and mouse. They also front-run slower human traders by sensing a buy order, then rerouting to a faster exchange to buy and then sell to the human at a slightly higher price. You’d think this obvious front-running would be illegal, but the exchanges make a lot of money by allowing the HFT computers to be close to the exchanges (co-location), so everyone looks the other way. If you’re an active human trader, you’re likely getting micro-scalped on every trade by HFT “liquidity providers.” For the record, we have so little portfolio turnover that I don’t worry much about these algovampires.

A startling stat: in 2008, the average holding period for a security on the New York Stock Exchange was two months. Seems brief to me, but OK. That average today?

Twenty seconds.

Yes, you read that correctly: the average holding period today is just twenty seconds. So much for Mr. Buffett’s quote, “If you aren’t willing to own a stock for ten years, don’t even think about owning it for ten minutes.” What about twenty seconds, Mr. Buffett? Don’t be surprised if there isn’t another flash crash due to the financial grab-assery of high-speed trading.

That leaves just ten percent of Mr. Market as a potentially fundamental-driven investor. We can categorize that ten percent even farther based on a spectrum of the method of analysis used by these discretionary investors.

On one end, you have technical traders who look for patterns in the price of a stock with little regard for the actual business. They’re short-term oriented and trade on speculation around news flow. They might not be able to name the CEO of the company they’re trading. Doesn’t matter as long as the price action is right.

On the other end you have long-term investors who diligently research all aspects of the business itself. The stock price movement is low on the list of concerns–they’re studying income statements and balance sheets. They want to understand the economics of the business, the management, and the industry dynamics. They think like owners. I don’t have to tell you which end of the spectrum you’ll find FSI.

“Investing without research is like playing stud poker and never looking at the cards.” — Peter Lynch

You start to realize how rare our investment approach is on an asset-weighted basis. We really are challenging the status quo. I’m fully aware it’s a dangerous place to be from a career standpoint, but it’s the only approach that makes sense to me. I agree with Jean Marie Eveillard’s observation: “I’d rather lose half my clients than half my clients’ money.”

As a physical reminder, we’ll be sending out clients a little something to make the point that they are owners of actual businesses, and not just squiggly lines on a graph.

A tangible example of how the new Mr. Market has changed the investment game might help. In 1963, American Express was involved in a scandal over salad oil. A huckster had been filling large storage vats of soy-based oil with sea water and AmEx had certified the oil was there when it wasn’t. AmEx faced $150 million ($1.5 billion in 2017 dollars) in potential losses from fraud and the stock price was cut in half overnight. Mr. Market questioned whether AmEx would survive the hit to their reputation. An unknown 33-year-old fund manager recognized the scandal wasn’t an existential threat and loaded up on AmEx shares. That fund manager’s name was Warren Buffett, and AmEx was one of his career-defining investment home runs. Berkshire still owns around seventeen percent of the company today.

What might happen should a similar scandal occur today? News of AmEx’s trouble would leak. The HFT computers would be the first to act and probably programmatically-sell shares they held based on news input. A slice of human traders would also feel inclined to sell the bad news.

Yet sixty percent of Mr. Market is not really paying attention. Yes, the stock would take some hit, but nowhere near a fifty percent chop. Let’s say it dropped ten percent–not enough for a young Buffett to get very excited. He has to wait for a fatter pitch to define his career.

Mr. Market overreacted to the AmEx news in 1963. Today, the market seems to underreact. For example, the same American Express fell only -6.4% when it was announced that Costco was severing their relationship with AmEx in 2016. Losing Costco could have been a more meaningful threat to AmEx’s future than a one-off salad-oil fraud. Mr. Market only yawned.

Of course, there will always be individual opportunities that pop up. But as the below volatility chart shows, there haven’t been a lot of wild price movements, like an AmEx cut in half, to take advantage of. My guess is there’s always been a bid from an index fund before the price can really dislocate.