By Rod Smyth, RiverFront Investment Group

A lesson regarding economic growth and stock volatility

Historically, long-term investors have not benefitted from betting against the combination of capitalism and democracy, even when global politics have been unsettled, unless the world’s stock markets are grossly overvalued – like they were in the late 1990s.

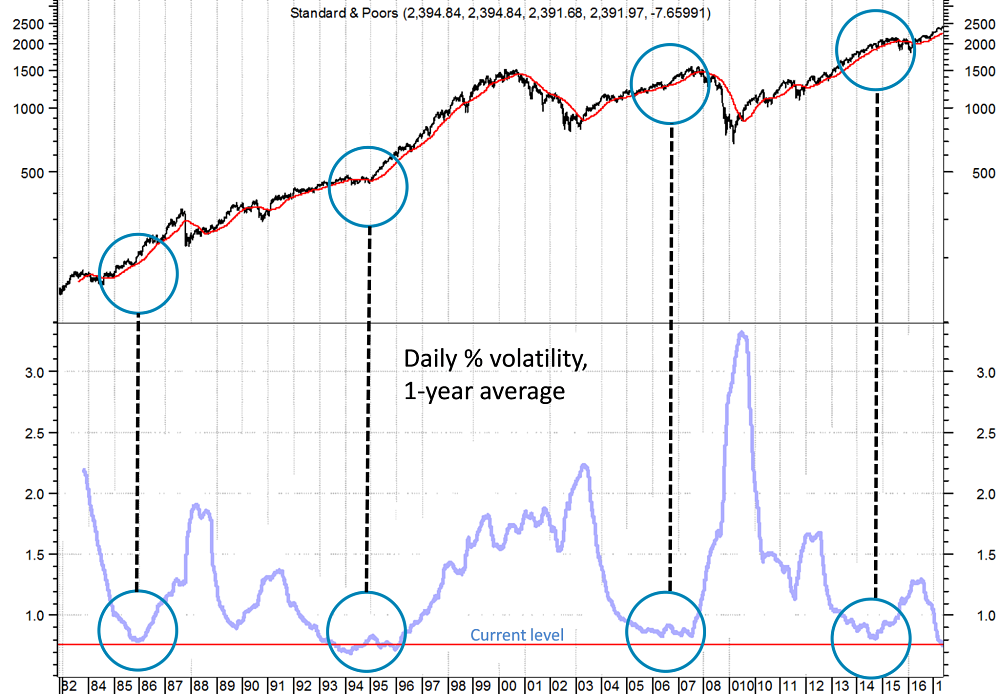

In essence, humans are resilient and highly creative, but still…human. Some today argue that the current extremely low level of volatility in US stocks implies investor complacency and is therefore a tactical sell signal. We agree that observed volatility is at extremely low levels by historical standards (see Weekly Chart below) and that it implies some complacency.

That said, we have tested volatility as a timing tool and believe it has limited effectiveness. Highs in volatility tend to be coincident with interim market bottoms, and extreme highs (usually brief) with bear market lows.

However, extremely low levels of volatility (like today) can last for a long time, and while they are sometimes followed by bear markets, this fact by itself is far from a reliable signal. Also, when low volatility does precede bear markets, there is often a gradual rise before the bear market sets in.

Historically, economic stability can change behavior, increase confidence

Few would deny that it has been a tumultuous year politically. Indeed, the whole global political debate has changed from the traditional post-Depression/World War ll discussion about the size and role of government. In that debate, the left wing sought to champion workers, civil rights and social/economic equality.

It produced a global safety net of government supported pensions, welfare and healthcare in most of the developed world, starting with FDR and taken up across Europe and Japan after the war.

At the same time, the right wing sought to champion commerce, globalism and the belief that everyone will be better off if government encourages largely unfettered capitalism. One of the right’s great champions in the 1980s, Margaret Thatcher is known for saying, “The problem with socialism is that eventually you run out of other people’s money”.

During the 1990s, a new generation of high-profile leaders from the left-leaning parties replaced the right wing dominance of the 1980s. Each of Bill Clinton, Tony Blair and Gerhard Schroder moved their parties to the right in order to get and stay elected. It was a time of increasing prosperity primarily set up in our view by the following major trends:

- A drive towards renewed efficiency and deregulation by companies and largely right wing governments in the 1980s.

- A once-in-a-lifetime expansion of the global economy to include the former Soviet Union, India, China and parts of Latin America.

- The transformation of human productivity through technology, innovation and communication.

Despite a vibrant political debate, electoral success during such a period of growing consumer and business confidence was mostly found in the center.

The economist Hyman Minsky warns that stability creates its own instability, and we have found that this is often true. Thus, the economic stability and unfettered capitalism of the 1990s led to overconfidence by banks/investors and, at times, excessive greed and unethical behavior by corporate leaders late in the decade.

Equally, the apparently unstoppable growth spurred by globalization produced a Darwinian outcome of winners and losers, which has contributed to the economic nationalism behind Brexit and the election of President Trump.

Perhaps more surprising to some is that today, it is the center-left that is championing free trade and open borders (despite the adverse effects on much of its base) and the right has moved to economic and social nationalism, also alienating much of its base.

Many traditional voters find themselves confused. Donald Trump and Marine Le Pen, both right wingers, struck a chord with disenfranchised blue collar voters, and France’s economic conservatives were without a candidate from the center-right and forced to choose between a potentially significant currency devaluation (Le Pen), or a former socialist (Macron).

Many people might wonder why there is such low volatility in stocks when political volatility seems high. In our view, a new form of lower growth economic stability has emerged in the last few years, first in the US and UK, but now also in the Eurozone. We think this explains much of the decline in stock market volatility, as companies have achieved robust earnings growth despite slow economic growth. (Outside the US, Japan is a poster child for this).

Also contributing to this trend, in our view, is that companies in the first quarter are beating the estimates they were making 6 months prior. We believe that this will get more difficult in the next six months, though, as expectations before the US presidential election were somewhat muted. Volatility is largely a measure of investor sentiment in our opinion, but we believe it is less reliable than other measures.

The chart above shows our preferred way to measure volatility, which is to take the % change between the high and the low on a daily basis and then smooth that out by using a 1-year average.