By David Haviland, Beaumont Capital Management

Since 2009, bond purchases by the Fed have driven rates to historic lows. The money supply has ballooned. Primary liquidity of corporate bonds has been significantly reduced. These are massive structural changes to our bond markets.

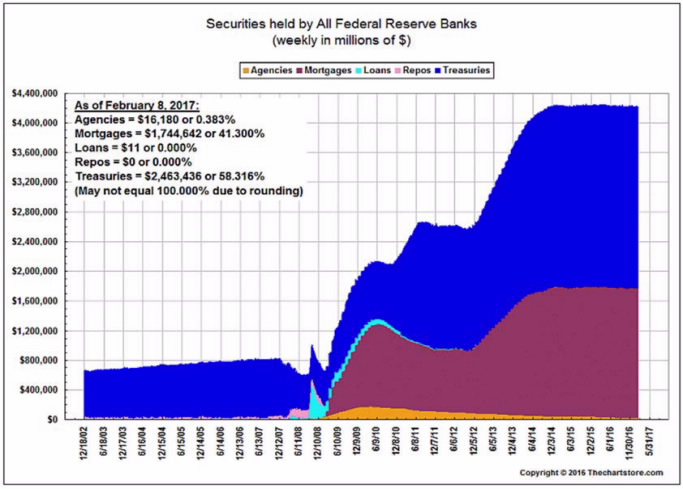

The Fed and its Balance Sheet

The 2007-2009 financial crisis has had many unintended consequences. First, to lend liquidity into the financial system and to help lower bond prices and interest rates in an effort to stimulate our economy, the U.S. Federal Reserve Banks (Fed) started buying bonds. With these purchases, the Fed’s balance sheet ballooned to almost four and a half trillion dollars. Over 41% of this are bonds backed by U.S. household mortgages. Today about 12% of the country’s household mortgages (over $1.7 trillion), and

$2.5 trillion of our country’s treasury bonds, are now owned by the Fed, our Central Bank.

The Overstimulated Monetary Base

Our money supply, or monetary base, is simply the total amount of currency in circulation plus commercial bank deposit reserves. Since the crisis, in addition to the Fed’s balance sheet quintupling, our monetary base has quadrupled from ~$850 billion to $3.6 trillion. These are two of the largest forms of monetary stimulus used to prevent the Great Recession from becoming another Great Depression.

We are grateful to have avoided another depression, but how do we get rid of the stimulus outlined above without sparking new unintended consequences?

Meanwhile, from 1/1/08 to 12/31/16, the U.S. economy (real GDP) has only grown 12.3% or 1.3% annualized growth1. In 2016 the U.S. economy had a record 11th straight year with real GDP growth less than 3%2. Politics aside, we wonder if the economy has grown enough to absorb the stimulus outlined above. Put simply, the monetary stimulus that has been injected into our economy is larger than anything tried before and we are concerned that any hint of inflation may cause interest rates to rise rapidly due to this monetary stimulus leftover in the system. We also worry that if the Fed or another entity starts to sell a significant portion of the bonds it owns (large selling means more supply without increased demand) it will likely just add to the rising rate fire.

Now let’s discuss corporate bonds. According to JPMorgan Asset Management, as of June of 2016, there were 4,333 stocks listed on U.S. exchanges. In comparison, according to PIMCO, there are over 300,000 corporate bonds issued and outstanding today. These typically trade over the counter and are non-standardized (meaning they have differing repayment seniority, covenants and indentures). PIMCO also shared that while the typical stock will trade 3,800 times per day, the most liquid corporate bonds only trade about 65-85 times a day. If liquidity were to begin to dry up like it did in 2007-2009, many bonds would not have a bid and could not be sold or only sold at fire sale prices.