Summer’s nearly through, and about 17.5 million students have returned to their colleges. To pay for that privilege, many will rely on student loans, which total about $1 trillion in the U.S. alone. The economic effects of that debt burden are increasingly a source of debate, with everyone from Wall Street critics to Congress and Fed economists worrying aloud about the value and financing of higher education. For the municipal bond market, this evokes questions about the business model of colleges and universities and, importantly, the credit quality of their bonds. While there are some valid concerns, we still see a stable fundamental outlook for the bulk of the sector. Consider the following:

- The market for higher education bonds is generally high in credit quality. 78% of muni bonds issued by colleges and universities come from institutions with an AA rating or higher. Furthermore, I believe it’s interesting to note that in 2012, the average public institution carried on its balance sheet 140 days’ cash on hand, while private institutions carried 263.

- Demand for a college degree remains supported. In general, college graduates tend to have higher income levels with fewer incidents of unemployment than individuals with only a high school diploma. This may sound like a platitude, but the evidence seems to bear it out, as illustrated in the chart below based on U.S. census data.

College Graduates Have Tended to Earn More with Lower Levels of Unemployment in the U.S.

Source: Morgan Stanley Research, Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Census Bureau. Data from most recent census.

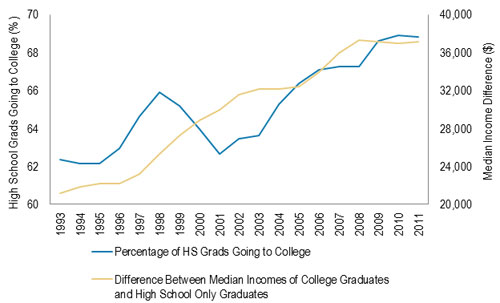

Not surprisingly, a greater percentage of high school graduates are attending college.

College Participation in the U.S. Trends Upward with Income Gap for College Graduates (3-yr rolling average)

Source: Morgan Stanley Research, National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Census Bureau. Data from most recent census.

- Key challenges exist but affect a smaller part of the market. Demand for a college degree may be strong, but universities’ ability to raise tuition may be limited over time, posing risks to their business model and credit quality. Personal income growth in the U.S., which has been subpar, is strongly correlated with enrollment. Not surprisingly, in 2012, the last year for which we have data, the number of families eliminating college choices for financial reasons spiked.

Furthermore, while the percentage of U.S. high school graduates going to college is projected to rise, the number of high school graduates is not expected to grow over the next seven years. Also, consider the rise of disruptive technology, like free online courses taught by credible professors, which over time could prove a viable, cheaper alternative to traditional universities. Taking it together, there are gathering pressures on incoming tuition payments, which account for 38% of revenues for private institutions and 33% for public institutions.

Yet some universities may be better positioned than others to cope with this risk. How? Revenue diversification and tuition discounting. The more revenue streams a university has, the less reliant it may be on tuition for financial health. Diversification allows a university the flexibility to use price discrimination (charging different tuition rates to different students) to sustain enrollment. This is called tuition discounting, and it reduces the “sticker price” at many institutions. Higher-rated, more financial-resource-rich institutions, which make up the bulk of the rated market, have the greatest capacity to discount, given, on average, less reliance on tuition (25% of revenues for AAAs vs. 86% of revenues for BBBs) and substantial higher total financial resources per student (over $1 million for AAAs, less than $23,000 for BBBs).

I believe the business model of higher education is likely to come under pressure over time. The good news for bondholders, however, is that this pressure is more acute for smaller, lower-rated institutions, which generally are a smaller portion of the higher education municipal bond sector.

Gradations of creditworthiness are indicated by rating symbols, with each symbol representing a group in which the credit characteristics are broadly the same. The symbols that are used by S&P to designate least credit risk to that denoting greatest credit risk: AAA, AA, A, BBB, BB, B, CCC, CC, and C. S&P appends positive or negative modifiers to each generic rating classification from AA through CCC. Ratings from BB+ to CCC- are below investment grade or speculative grade.